Writer and professor Asimov drawn into communist paranoia

Among the anti-war protesters of Boston University in the 1960s, prolific science fiction writer and biochemist Isaac Asimov made a place for himself as a professor and mentor. Asimov wrote about everything from mystery and fantasy to science fiction to popular science, but he never wrote about communist paranoia or Soviet spies. Regardless, the Federal Bureau of Investigation found reasons to investigate Asimov as a possible Soviet informant during the Cold War era.

Asimov, who had been associated with BU School of Medicine since 1949 and a professor of biochemistry since 1955, was the subject of his own FBI investigation while they were looking for the man behind the code name, ROBPROF.

In the speculative story of ROBPROF, a Soviet informant working in American academia in the field of microbiology, Asimov became a potential protagonist.

Conor Skelding of MuckRock, an open records website, filed a Freedom of Information Act request for the FBI documents detailing the investigation into Asimov, which he posted on the site on Nov. 7.

Though no information was ever found during the time of their investigation that definitively linked Asimov with the Soviets, Asimov’s file was just one example of the paranoia regarding an individual’s status as a possible Soviet Union agent, said William Keylor, a BU professor of international relations.

“My impression of [Asimov] was always that he was a liberal and opposed to the war in Vietnam—I know that for a fact,” Keylor said. “He was very critical of the Nixon administration, but I never heard anything about him being connected with the Soviet Union. That came as a real surprise to me.”

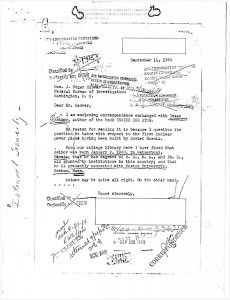

On Sept. 14, 1960, two weeks into the fall semester at BU, a tipster sent a letter to J. Edgar Hoover, who was the director of the FBI at the time, and shared personal correspondences he had with Asimov.

“My reason for sending it is because I question the position he takes with respect to the first nuclear power plans having been built by Soviet Russia,” the tipster wrote in the letter.

He continued to explain his reason for concern about Asimov, which was primarily that Asimov was born in Petrovichi, Russia.

Later files explain that while Asimov was born in Petrovichi in 1920, he arrived in the U.S. only three years later and was naturalized by the time he was eight years old.

The tipster ended the letter with, “Asimov may be quite all right. On the other hand, …”

Hoover politely responded, thanking the tipster for the information and included some material on the subject of communism, including a pamphlet entitled “Communist Target — Youth.”

However, the FBI noted while at the time they had no existing records on Asimov, they did have existing records on previous instances in which the tipster informed the FBI of information he found suspicious, for example, a 1957 letter that included information regarding the Russia Revolution 40 years before.

“He was thanked for his observations,” the note concluded. “It is believed above acknowledgement is best suited although we have no particular interest in his observations.”

Though the FBI found the tipster’s information essentially useless, Asimov fell under their radar again five years later. In 1965, the FBI began gathering more information on Asimov after revisiting a list of people’s names from New England’s Communist Party U.S.A. (CPUSA), who were contacted for recruitment, but there was no note on Asimov’s name saying he had been contacted.

The FBI then connected the Communist Party to science fiction magazines. Science Fiction magazines did a large amount of “blind” publishing for the Communist Party according to the informant. They connected this snippet of information to Asimov because, though he was a cancer researcher at Boston General Hospital at the time, he was also contributing stories to Science Fiction magazines with apparent anti-war themes.

The FBI was on the lookout for a Soviet informant with the code name ROBPROF. However, the FBI believed ROBPROF to be a noted person in the field of microbiology, not Asimov’s field of biochemistry.

Regardless, the documents stated, “Boston [FBI branch] is not suggesting that ASIMOV is ROBPROF as [redacted] has advised that ROBPROF is in the field of microbiology. However, as in the case of [redacted] he should be considered as a possibility in light of his background, which contains information inimical to the best interests of the United States.”

The case was placed on a pending inactive status until more definitive information was found.

In 1967, the SAC Boston wrote to the federal branch that, “He is employed as a teacher at Boston University and no derogatory credit data is contained therein,” in the last recorded document investigating Asimov on Dec. 11, 1967.

During the Cold War period, communist paranoia in the United States was common. However, this paranoia had mainly died down thanks to a change in political leaders by the 1960s, Keylor said.

For a period during the Cold War, the government investigated many other faculty members at American universities. Beginning around 1947, some universities required their professors to sign loyalty oaths, swearing they were loyal to the United States. Some were called before various committees like the House Un-American Activities Committee for questioning.

While university professors were not singled out as the only group widely investigated by Congress and the FBI, there were among people in a position to have a broad influence.

“There was the concern that they [professors] were poisoning the minds of youths,” Keylor said.

The motion picture industry was under fire for the same reason, Keylor said. Hollywood screen writers were accused of injecting pro-communist ideas into films during the 1940s and 1950s.

“The powerful effort to identify suspected communists came to an end in the early 1960s,” Keylor said. “Then it sort of was revived under the Johnson administration, after the Kennedy assassination, because Johnson was convinced that the anti-war protests against the Vietnam War were orchestrated by the Soviet Union.”

However, the anti-war movement was a completely home-grown movement of youth with no connection to the Soviet Union, he said.

“Asimov was opposed to the war, and it was guilt by association,” Keylor said. “These students on BU’s campus were opposed to the war, so they assumed there must be a connection.”

The student rebellions in the 1960s had a lot more to do with the fact that the U.S. was drafting a conscription army than any Soviet connection.

“Some of the college students who led the protests against the war in Vietnam were feeling a sense of guilt,” Keylor said. “Here they were on the BU campus enjoying all the privileges of being a college student and other young men were being sent to Vietnam — killed, wounded — so they decided to go out and protest this injustice.”

The investigation into Asimov probably had more to do with his vocalization against the war in Vietnam more than his Russian heritage, Keylor said.

The file on Asimov spanned the Kennedy and Johnson administrations — years when the paranoia of the previous decade was beginning to lighten.

“The bottom line is that by the time that Asimov was being investigated, that [communist paranoia] was no longer a major concern of the government,” Keylor said. “It was the Vietnam War and the protests against the Vietnam War. Johnson — and later Nixon — were trying to find out if any of the leaders of the anti-Vietnam movement were connected to the Soviet Union.”

The congressional investigations, the House Un-American Activities Committee and Sen. McCarthy’s mission did not result in very many Communist spies being exposed, though there were a few exceptions including Alger Hiss in the 1940s.

“The Red Scare was an attempt to expose those Soviet spies, but it really didn’t succeed in getting those people,” Keylor said. “It tarnished the reputations of a lot of innocent professors and innocent citizens because of earlier affiliations that they had been left wing years before the Cold War even began.”

While the investigation seemed to have veered in a different course, Asimov continued to be a major author and academic for many years until his death in 1992. Today, Asimov’s 1960s career remains in the form of a large collection in the Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center, housed in Mugar Memorial Library.

This is an account occasionally used by the Daily Free Press editors to post archived posts from previous iterations of the site or otherwise for special circumstance publications. See authorship info on the byline at the top of the page.

The question you should ask and answer is ” why is the taxpayer funded death squad called the FBI still in business now that we know FBI agents helped assassinate President Kennedy and Martin Luther King”

To view an annotated bibliography of books dealing with crimes committed by FBI agents visit the news section at ldsfreedomforumdotcom There is also over 300 pages of arrest records of FBI agents arrested for pedophilia and other crimes at the news section.