As adjunct professors at many institutions of higher education fight for adequate employment benefits, a report recently issued by Congress recognizes the challenges part-time professors face.

Issued by the House Committee on Education and the Workforce, the report highlights the struggles faced by adjunct professors in the United States trying to earn a living from their adjunct salary. It is a response to a government-created forum that asked adjunct professors to express their career concerns.

The report marks the first time the government has recognized adjunct faculty mistreatment at universities as a growing issue, said Malini Cadambi Daniel, a spokesperson for an organization that aims to garner better benefits for adjunct professors called Adjunct Action.

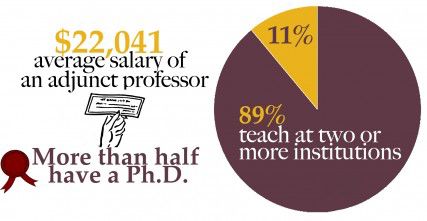

“When you think about how little adjunct faculty make, how few benefits most of them have — no health insurance, no retirement security, how they are forced to reapply for their jobs so they have no job security — it’s shocking,” Daniel said. “If the debate in this country is about income inequality and whether we need to raise minimum wage, this is perfect timing.”

Many adjunct professors, such as Andrew Sheehan, an adjunct professor of computer science at BU’s Metropolitan College, work full-time jobs during the day to support themselves while teaching classes.

“I work during the day as a programmer,” Sheehan said. “Being an adjunct professor doesn’t actually give very much money. Adjuncts don’t get any benefits really …Mine come from my full-time job. Most adjuncts teach one, maybe two classes, and that definitely wouldn’t allow you to afford rent, student loans, car, gas, utilities, other bills.”

Gillian Mason, a former BU adjunct professor and current activist for Massachusetts Jobs with Justice, said one of the most cloying concerns among adjunct professors, particularly those looking to become full-time employees, is that there are few opportunities for advancement in the adjunct professor system, which is economically beneficial to universities.

“BU adjuncts don’t have a union, so there’s really no sense that adjuncts have a voice on the job at BU,” Mason said. “… A lot of folks have the idea when they’re doing that of, ‘This is just temporary, and when I graduate, I’m going to get that tenure-track job and it’s going to be awesome.’ Unfortunately, what we’re finding more and more is that tenure-track jobs aren’t easy to get. You’re going to be an adjunct for a lot longer than you think you are.”

Sheehan said although adjunct professors are often looking for ways to become full-time professors, many obstacles prevent them from receiving the full tenure-status they desire.

“It would be nice if an adjunct wanted to go full time and the opportunity afforded itself at the university, but there are a bunch of barriers that don’t let that happen,” Sheehan said. “That’s the way it always has been.”

The tenure review process varies from one university to another, and even from one college to another within Boston University, but it tends to be a lengthy process with numerous steps, according to the Faculty Handbook.

At BU, the tenure review process typically requires the candidate to meet the approval of several officials and committees, starting with tenured faculty members of the department and sometimes approved, non-tenured faculty members. They discuss the candidate’s qualifications and take a vote. If approved, the candidate’s application goes through the department chair, an appointment, promotion and tenure committee within the school, the school dean and then the provost. From there, the application requires review from a larger committee, the provost and the president.

Warren Mansur, an adjunct professor of computer science at MET, said adjunct professors should regard their teaching positions as extras unless they hope to pursue careers as tenure-track professors.

“They [adjunct professors] are taking a part-time job, and can’t expect to get the same benefits as a full-time job,” Mansur said. “My experience is that being an adjunct means you’re doing something extra job on the side. It’s a part-time job … If you want it to be a full-time job, you should apply to be a member of the full-time faculty.”

This is an account occasionally used by the Daily Free Press editors to post archived posts from previous iterations of the site or otherwise for special circumstance publications. See authorship info on the byline at the top of the page.

A small minority of adjuncts, as in law, have careers in their chosen professions and do not depend on their part-time teaching for a decent income. The majority of adjuncts, in fields like the humanities, try each term to cobble together several extremely low-paying teaching assignments in one or more institutions so as to eke out a living. Like many employees in other fields today, their incomes are so low that many qualify for food stamps. Today’s adjuncts might have qualified for tenure-track appointments in better times, but these days they have little chance of getting permanent teaching appointments. They are many, permanent positions are few, and their predicament allows their exploitation by universities, which minimize their teaching costs by relying increasingly on adjuncts instead of hiring faculty on multi-year contracts with benefits, offices, the right to participate in university governance, etc. Universities’ increasing replacement of regular faculty with adjuncts is an academic tragedy and scandal.