Do you know which branch of the U.S. government has the constitutional authority to declare war?

Do you know which branch of the U.S. government has the constitutional authority to declare war?

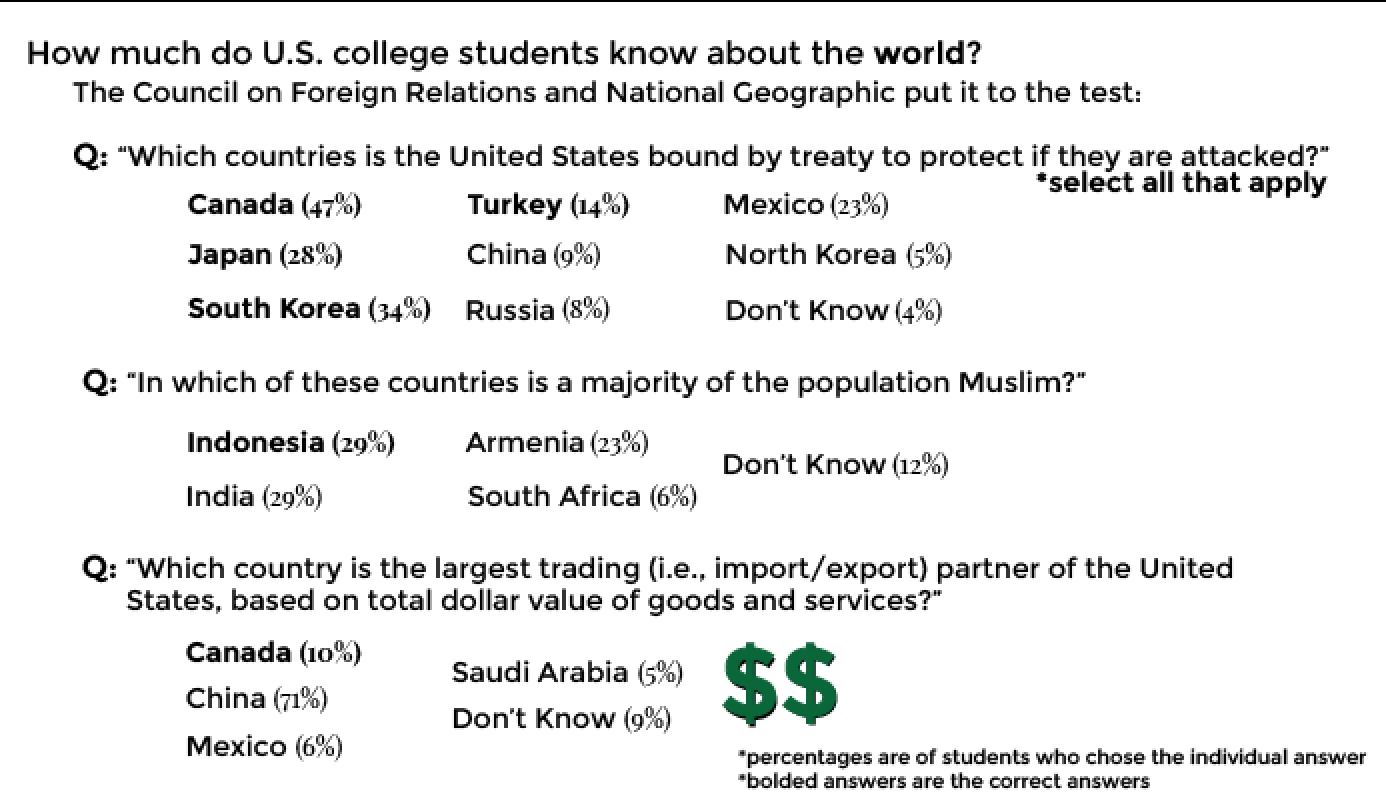

This is an example of a question asked to 1,203 surveyed U.S. college students in May. Researchers from the Council on Foreign Relations and National Geographic asked the students 10 randomly-generated questions, out of 75 possible, to gauge how much they know about the world.

The right answer is the legislative branch — approximately 30 percent of students answered it correctly.

Overall, 55 percent of questions were answered correctly, prompting researchers to conclude Tuesday that American college students do not know enough about the world to smoothly navigate the world’s stage.

Students who completed the survey said knowledge of geography, world history, foreign cultures and world events are important, and universities are trying to provide them with such knowledge, according to CFR Vice President of Education Caroline Netchvolodoff.

“The problem is more that they are not requiring students to take [courses that teach about the world],” Netchvolodoff said. “We want to raise the conversation about the need for colleges to require that students — no matter their course of study — graduate with knowledge that equips them to succeed as citizens and professionals in a global era.”

Arnaldo Franco, a freshman in the College of Arts and Sciences, said it is increasingly important that students be informed about world events and news.

“There are things that matter [but] do not get too much attention,” he said. “Everyone should be informed, but the students should be a priority, because they are the ones who have the lifetime in order to make the change.”

William Grimes, an associate dean at the Frederick S. Pardee School of Global Studies, wrote in an email that while the CFR report offers an interesting perspective, the survey is so short that it’s hard for researchers to offer a systematic assessment on what students know about history and current affairs.

“There are a few reports of this sort every year that get media attention,” Grimes wrote. “But I don’t think there’s any real consistency in terms of the content or an obvious way to measure whether responders’ level of knowledge is sufficient or insufficient.”

Bailey McConnell, a junior in CAS, said BU students generally know what’s going on in the world because BU’s diverse campus allows them to be more aware of world issues.

“Our campus is not really in a bubble, like other schools might be,” she said. “We’re pretty close to a big city, and we’re pretty diverse so that it’s hard not to be aware.”

Igor Lukes, an international relations professor in Pardee, said some students are far more knowledgeable about world politics than their peers.

“I’m sure that some are very well informed and some perhaps less so,” he said. “The students I meet in my classes astonish me every day with their understanding of the most minute events in the world today.”

As for students who want to be more aware of politics, Lukes recommended reading newspapers such as The New York Times.

“I would also tell them that if it’s impossible for them to get rid of their smartphones, they should at least get out of Facebook, and instead subscribe to The New York Times,” he said.

Olivia Beutel, a freshman in the Sargent College of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences, said teenagers aren’t interested in keeping up with world events.

“I feel like these days, teenagers and young people aren’t really interested in paying attention to the news and reading newspapers and things like that,” she said.