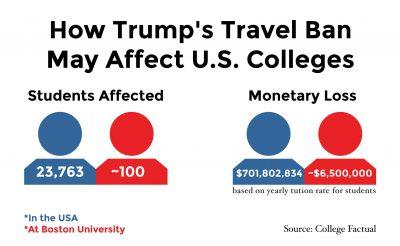

U.S. colleges could lose up to $700 million in revenue per year if President Donald Trump’s executive order, which prevents citizens of seven Muslim-majority nations from entering the United States for 90 days, becomes permanent, according to a report released Tuesday by College Factual, a higher education research firm.

Boston University’s Dean of Students Kenneth Elmore said that though financial loss would most likely occur, the order’s impact would go far beyond just economics.

“Of course that would impact us — these are people who are regularly in our community,” Elmore said. “And it’s not just the economic impact, you worry about the long-term impact this has for a student, a young person out in the world, to come to the United States.”

He said the executive order could negatively impact the university in a variety of ways.

“I mean it’s a real big hit for … higher education,” Elmore said. “There’s that emotional impact too, that community impact that we will miss if those students decide not to stay here. I think the impact on higher education could be far reaching when we think about the pluralism of Boston University. That’s pretty important.”

Kevin Lang, a BU economics professor, however, said that the financial impact of Trump’s order would probably be minimal.

“I doubt that there is a large financial impact on selective institutions like BU,” Lang said. “They should be able to replace the students they lose with others. The aggregate effect would depend on how much tuition the foreign students are paying.”

BU President Robert Brown wrote an op-ed in the Boston Globe criticizing the executive order.

“The order … may be more symbolic than effective in the long run, but the symbolism is extremely troubling, because it plays to base fears and bias against foreigners and sets us on a path to see every immigrant as a threat. In universities, we see things very differently,” Brown wrote. “The world is watching what we do. Segregating international students and immigrants on the basis of religion or nationality sends the message to the world that the United States is not the land of freedom and opportunity that we value, but a place of bias and suspicion.”

On Friday afternoon, BU — along with eight other Massachusetts institutions of higher education, including Boston College, Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Harvard University — filed an amicus curiae brief stating their support of the plaintiffs suing Trump, the U.S. Customs and Border Protection and others. According to the document, the brief was filed “to provide insight into these repercussions from the unique perspective of institutions of higher education.”

The civil suit stated Trump’s executive order would damage higher education by limiting its diversity.

“[Amici] employ professors, researchers, and lecturers — many of whom are citizens of other countries — to teach students, to conduct groundbreaking research, and to share their unique perspectives on a range of issues,” the document read. “Amici’s ability to succeed as institutions of higher education depends, in large part, on the ability of students and scholars to collaborate across borders. The Executive Order at issue in this case imperils that exchange and will have damaging repercussions for amici, for all other similarly situated academic institutions, and, ultimately, for the nation and the world as a whole.”

BU spokesperson Colin Riley wrote in an email about the difficulty of attempting to predict the future repercussions of this legislation.

“The situation is fluid, as President Brown says, and so it is premature to address possible ripple effects at this time … Also, the [executive order] is temporary at this time,” Riley wrote.

Riley explained the students from impacted countries — Iran, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria and Yemen — only make up a small percentage of BU’s overall international student population.

“There are nearly 100 students and 16 scholars at BU from these countries, but fortunately all were on campus before the EO went into effect,” Riley wrote. “As you may know, there are some 9,000 international students at BU. That means the EO impacts about one percent of the international students/scholars at BU.”

Several students said they, too, disapprove of the executive order.

Fatima Dainkeh, a first-year graduate student in the School of Public Health, questioned the motives of the ban.

“I’m not sure I understand why it’s happening,” Dainkeh said. “A terrorist doesn’t have to come from Iraq or Iran, a terrorist can come from right here in our country. I think what we are doing is burning bridges and not really trying to make sure everyone’s safety is our best interest.”

Varsha Srivastava, a junior in the College of Communication, said the ban’s limitations are significant.

“I think [the ban] is extremely unethical,” Srivastava said. “People supporting it will say it’s not specifically a ban on Muslims, but you can’t deny that’s where it started, just because of what he said during his campaign. It does not only physically limit people, it limits opportunities for learning, for the students studying here who can’t come back if they leave.”

Briana Lopez, a sophomore in the College of General Studies, said the order will be damaging to international students from affected countries both physically and emotionally.

“[BU students from banned countries] came here to get an education,” Lopez said. “They’re here because they are smart, they want to learn something and they want to be able to make an impact in the world. How are they going to be able to do that when they’re too busy not knowing when they are going to be able to see their families?”