Gender inequality has limited women’s ability to pursue a career in the sciences for years, resulting in fewer paper citations, less funding and fewer job opportunities for female scientists, according to a 2015 article in Nature, an international weekly journal of science.

Since Azeen Ghorayshi’s investigative story on astronomer Geoffrey Marcy, a professor at the University of California, Berkeley who sexually harassed female undergraduate students, more female scientists have revealed their experiences with sexual assault and harassment.

“Sexual harassment isn’t the reason why we don’t see gender equity in STEM fields,” said Ghorayshi, a BuzzFeed science news reporter. “It’s a system in the science culture that enables that to happen.”

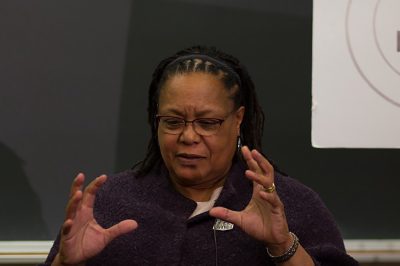

Ghorayshi spoke at the MIT Communications Forum on March 9 and was joined by three other speakers: Sarah Ballard, an astronomer and a Torres Fellow for Exoplanetary Research at MIT, Evelynn Hammonds, a history of science professor and Christina Couch, a science journalist.

Sexual harassment happens to many women in the STEM subjects, including science, technology, engineering and mathematics, but most authority figures who have the power to fix the problem don’t see it as a priority to address the issue and discipline those who harass female scientists, Ghorayshi said.

“It says something about the power dynamic in higher education, and who listens to who and who is valued and not,” Ghorayshi said.

A study found that 26 percent of female researchers had reported assault at field research sites, and another 71 percent reported harassment, according to a 2014 Survey of Academic Field Experiences.

Women often face many obstacles like these in their workplaces, such as attacks for their perceived emotional instability. Male scientists have expressed that they don’t want to work with women in the lab because the women could fall in love with them or get upset easily, Ghorayshi said, who encountered such comments on her case-by-case reporting.

She said men might believe their science is more important than their behavior, which explains why they treat women in the sciences the way they do.

“I think that for a long time, these women were relying on each other and support networks for women in science, but for an actual change to happen, we need the whole field to get together,” Ghorayshi said.

Wafaa Tali, a sophomore studying human physiology in Boston University’s Sargent College of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences, said she agreed that men and women need to get together to fix gender inequality in the sciences.

“I’m not a clinical professional, but as a student, I can sense the imbalance,” Tali said. “It’s not intentional, it’s just society.”

Men should be more aware of their actions, Tali said, but the problem is highly dependent on the individuals who make the decisions about who gets hired.

“At first it’s rude, but at the end of the day I feel empowered because you realize that there really is no division,” Tali said. “No one is better than the other.”

In addition to discussing the barriers to gender equality in the sciences, the speakers also talked about steps to overcome these obstacles.

The media is covering sexual harassment and gender equity a lot more but it’s led to many questions, said Couch, a coordinator for the MIT Communications Forum.

“People are asked if it’s an issue specific to science, and it’s not,” Couch said.

She agrees that there is a lack of harassment training and recognition of what it feels like but the forces that keep these stories under wraps need to be revealed.

“For a victim to go public, that’s a tough thing for them to do,” Couch said.

In response to the Marcy case, Congresswoman Jackie Speier introduced a bill in 2016 requiring universities to report cases of sexual harassment to federal funding agencies. However, the bill was not enacted.

Professional societies should also establish concrete codes of conduct in the workplace and define what they stand for, Ghorayshi said.

The American Astronomical Society created an anti-harassment policy in 2015 that said they are “committed to the philosophy of equality of opportunity and treatment for all members, regardless of gender, gender identity or expression, race, color.”

At the university level, Ghorayshi said administration needs to provide better sexual harassment training for faculty members because it’s one step closer to creating a fair and respectful environment for all individuals.

Ghorayshi also said hiring is “huge” and managers need to employ more women in the STEM fields.

“We need to take active steps to address what people are scratching their heads about.”