There are many ways that teachers try to reach students, but none, perhaps, are as effective as the illustrative example. Case in point: Daniel F. Davis was teaching a class where was he trying to explain the crouch that runners use to begin a race.

At first, Davis tried to describe the crouch. Then, the 70-year-old went further: he broke from the lesson and performed the crouch himself, lowering to all fours.

“He was making a point, as a teacher,” said Philip Tate, a colleague of Davis’s at Boston University’s School of Education. “If you’re demonstrating, you might as well go all the way.”

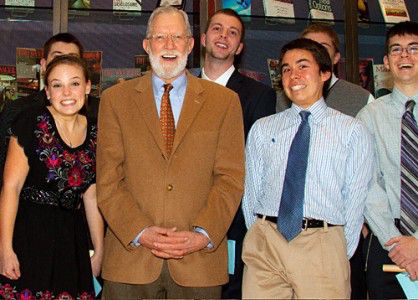

Davis, a clinical assistant professor of education, died on Oct. 19 of a heart attack in Udaipur, India after teaching classes in Mumbai. He was 70 years old.

Described by colleagues and students as a “compassionate,” “humble” and “humorous” teacher, Davis grew up in Coney Island, New York, according to a death notice published in The Boston Globe. He received his bachelor’s degree at Owego University B.A., and later received his master’s at Brooklyn College and a Ph.D. from Ohio State University.

For 30 years, Davis worked at Stoughton High School in Massachusetts, teaching social studies and eventually becoming school principal. He left the school eight years ago to teach at BU, where he worked with “everybody from freshman advisees to doctoral students,” Tate said.

“I personally will remember him as a passionate man constantly in the service of his students, and of education in general,” said former student Scott Delisle, SED ’13, in an email.

The coauthor of The United States Since 1945 and A History of the World, Davis never left his history teacher past behind. According to his professional biography on the SED website, Davis’ specialty was “the development of concept formation, critical thinking, and the art of questioning as they relate to the teaching of history and social science.”

“I have known Professor Davis for four years and he has impressed me by the range his understanding of history and his complete commitment to training his student teachers who loved him,” said Hardin L. K. Coleman, SED dean, in an email. “Most important, he was incredibly caring.”

Though colleagues regarded him highly, Tate said, Davis was a humble man. He used to stop by the offices of other professors almost every day to say hello and ask for advice.

“I used to think why is this expert teacher asking me for advice?” Tate said. But whatever answer Tate gave, he said, Davis would take seriously.

“He was very, very modest about his accomplishments,” said Thomas Cottle, a professor of education at SED and a close friend of Davis. “He cared about education and about the education of the young people.”

Cottle described Davis warmly, saying that the pair would call each other “darling” and “sweetie.”

Cottle recalled one speech he gave several years ago that Davis attended. After the speech, he said, Davis gave

Cottle a kiss on the cheek and hugged him.

“He was a loving guy. I have no problem revealing that,” Cottle said.

Davis will not have his influence end with the students he worked with, Cottle said. Rather, his influential style will ripple onward.

“You teach people who then teach people,” Cottle said. “In ten years, he had about 500 students – who later influence so many.”

“We’re all scrambling to figure out how to replace him,” Tate said. “He did so many things that we just assumed that they’d be taken care of. He leaves truly a big hole in our School of Education.”

Davis leaves his wife of 48 years, Barbara; his son, Jeff Davis; his daughter Jill Davis; his sister, Gwendolyn; and four grandchildren.