Protein is everywhere. It’s in that burger you had for lunch, the clam chowder you had as a mid-study snack and even in your body, which solidifies the adage: “You are what you eat.” And the presence of protein in so many foods has now become good news not only to bodybuilders and athletes. A study by researchers at the Boston University School of Medicine suggests that a high-protein diet correlates to lower risk of developing high blood pressure.

In the arena of heart health, this finding could offer insight into a new dietary method of preventing this common medical issue.

“Increased blood pressure puts considerable stress on the heart,” said Dr. Frank Naya, associate professor of biology and associate chair of the cell and molecular biology department at BU. “If blood vessels are constricted, the heart has to pump much harder to get the blood through the smaller opening of the vessels. And that is why lower blood pressure is better. The heart doesn’t need to contract as forcefully to get blood out of the heart and into the vessels.”

According to the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, about 1 in 3 American adults suffer from high blood pressure. Such statistics give incentive for people in the United States to take preventative action. College students are particularly prone to malnutrition during the school year and could benefit from the study’s pro-protein findings.

“I would absolutely think of changing my diet,” said Caren Stuebe, a sophomore in the College of Arts and Sciences. “As an athlete, what you put into your body definitely impacts your performance.”

The study, published in the September 2014 issue of the American Journal of Hypertension, found that adults who consumed approximately 100 grams of protein a day had a 40 percent lower blood pressure compared to those with a low intake of protein.

For the study, researchers followed healthy participants from the Framingham Offspring Study for an 11-year period. Each participant was analyzed for his or her systolic pressure, the pressure in arteries during heartbeats, and diastolic pressure, the pressure in arteries between heartbeats. These two measurements comprised the participants’ blood pressure fractions, which were recorded alongside each participant’s dietary habits.

After a close examination of the data, a verdict was reached: Protein keeps blood pressure down. Regardless of body weight, participants with the highest protein intakes were found to have upwards of 40 to 60 percent lower risk of high blood pressure.

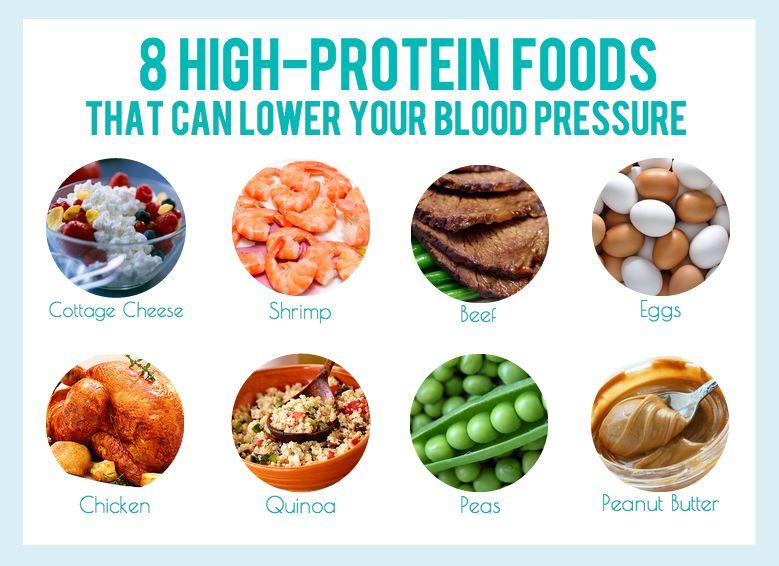

But before rushing for that third helping of protein-heavy food, Naya suggested holding off until there can be further investigation about the relationship between protein and blood pressure. But a daily intake of a fair amount of poultry, nuts or fish could serve as a healthy start.

“The higher protein intake may alter your cellular metabolic pathways, and perhaps this results in less circulating fatty acids or lipids that may stick to the walls of vessels and constrict them,” Naya said. “But this is only speculation. It requires further study.”

Just as the cardiovascular benefits of protein are in the works, so are many attitudes toward mindful eating.

“What stops people from just thinking about eating healthier to actually eating healthier is convenience,” Stuebe said. “The dining halls offer a lot of options, but I think there could be more basic protein options available.”

Adjusting dietary habits can be difficult when the benefits lie distantly in the future. Those already indulging in a high-protein diet, however, perhaps need not make any further changes.

“I am past the point of changing my diet since I already eat a lot of protein to begin with,” said Benjamin Long, a sophomore in the College of General Studies. “But now knowing this, I’m glad to know my decisions to eat like this are justified.”