The National Center on Family Homelessness reported Monday that Massachusetts ranks third best in the nation in addressing child homelessness, an epidemic that reached a historic high nationwide.

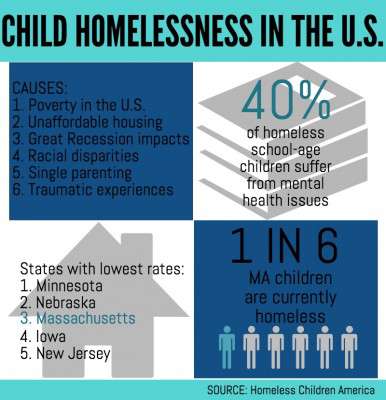

“When you look at the demographic of families, poor single female-headed households that are raising young children have limited education and have limited employment opportunities,” said Carmella DeCandia, director of the NCFH. “The poverty level and lack of affordable housing are the two biggest structural factors that cause homelessness. People need affordable housing, and parents and mothers need services to help with their education and employment.”

The report analyzed the U.S Department of Education’s annual account of homeless children in the school system with U.S Census Bureau’s data of the overall homeless population. Taking into consideration that 51 percent of homeless children are under the age of six, NCFH reported that 2,483,539, or 1 in 30 children, experienced child homelessness in 2013.

Robyn Frost, executive director of the Massachusetts Coalition for the Homeless, said the Commonwealth decreased the number of kids growing up in Massachusetts in poverty from 1 in 8 to 1 in 6. The Commonwealth’s programs fighting homelessness are the reason behind its positive rating, she said.

“Massachusetts ranked very high for its ability to have programs and initiatives that are helping those living in poverty, which is what these kids are living in. Homelessness is a derivative of poverty,” she said. “That’s why the numbers nationally and statewide are so high, because families are living in such poor economic means, their incomes, even if they’re working at a moderate rate on minimum wage, have not been able to keep pace.”

Massachusetts’ high ranking was also due to the accessibility of publicly funded family shelters, Frost said. Compared to other states, homeless shelters in Massachusetts are funded by the Commonwealth, enabling it to be at the forefront for services like early childcare, daycare and voucher rental programs.

DeCandia said the center examines four domains of child homelessness to gather a composite ranking for each state: the extent of homeless, analyzing the number of homeless children in the state per capita; the risk factors, the highest of which being the number of households headed by single mothers; the disparity between wages and affordable housing; and the homelessness policies of each state.

“When kids become homeless, they don’t just lose their home, they lose their sense of place in their community, get split up with their families. They are facing really tough choices,” she said. “Kids might also attend multiple schools in one year because they’re moving around a lot. That kind of instability, especially if they have been exposed to violence and those kinds of stresses, that really affects the child’s development.”

While Frost said Massachusetts has facilitated many of the needs for homeless families, there is still a need for improvement.

“The state-funded shelter program is busting at the seam, and yet our state tries to add more regulations to keep people out of shelter,” she said. “Right now we have over 4,000 family shelters. Three or four years ago, the number of families in shelters was under 1,000, but with the downturn of the economy, it has skyrocketed.”

Frost said that the disparity between wages and affordable housing is the primary cause of homelessness in Massachusetts.

“In Massachusetts, the minimum wage is $8 an hour, and if you want a two-bedroom apartment, you need to be making $24 an hour to afford that apartment, so mom would have to work three full time jobs,” she said.

Several residents of Massachusetts said more government intervention is needed in addressing the issue of child homelessness.

“Combating homelessness requires a strong government intervention through various programs, housing subsidies and job programs,” said John Callahan, 56, of Jamaica Plain. “The problem is it takes money that comes from taxes. In Massachusetts, and more so in other states, people don’t like to pay taxes for things they don’t see directly helping them.”

Stacy Malone, 42, of the North End, said homelessness among children is an especially important cause because of the long-term effects it will have on them.

“Not only do they not have a home and are not getting food, but it’s hard for a child to concentrate on education,” she said. “And if a child doesn’t have an education, home or food in their belly, then how do we expect them to be able to participate in society? And how do we expect them to grow and be able to enjoy the fruits of their life?”

Anne Schmidt, 63, of Brookline, said she was skeptical of the extent of the Commonwealth’s efforts dealing with child homelessness.

“I’m surprised Massachusetts is so highly ranked, because the city of Boston can do a lot to more to address the issue of homelessness, especially for housing people,” she said. “Massachusetts is ranked so highly because we have a better source of revenue and are more well off than a lot of states and have more money to put into programs, but there’s still not enough.”