If having a child meant hurting them, how far would people go to fix it?

Science has known for a long time that everything a living being is boils down to long sequences encoded in DNA, passed down from generation to generation. Genetics, the study of these sequences, marches forward every day, finding ways to help those cursed with flaws in their codes.

Thanks to a recent decision by the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, the latest genetic issue to seize the spotlight deals with the creation of a so-called “three-parent child” to combat the transmission of mitochondrial diseases. The House voted Feb. 3 to allow the creation of these children, a decision unprecedented in international law.

“Well, what’s being proposed is something very similar to what was done 25 years ago. It was very controversial at the time,” said Martin Steffen, professor of biomedical engineering at the Boston University School of Medicine. “There has been quite a lot of press attention to this. But less of a vehement response.”

Mitochondrial diseases deal with an individual’s inability to properly generate energy within their cells, which can lead to fatigue, compromised immunity and in some cases, the failure of entire body systems. The three-parent child proposal would ensure that mothers suffering from mitochondrial diseases would not pass the disorders onto their offspring.

The intensity of mitochondrial diseases varies, Steffen said.

“There are cases that are more severe … people know it’s wrong early on,” he said. “The intensity of the disease has a wide range.”

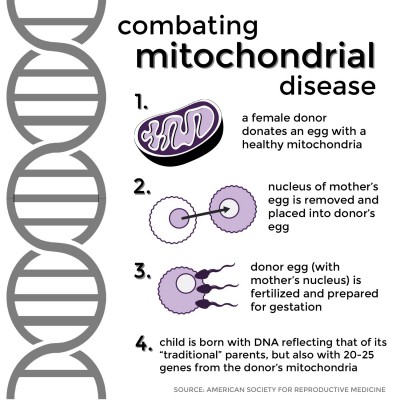

The process involved is similar to in vitro fertilization. A healthy female donor donates an egg with healthy mitochondria. The nucleus of the mother’s egg is removed and placed into the donor egg, which is subsequently fertilized and prepared for gestation. When the child is born, its DNA overwhelmingly reflects that of its “traditional” parents — over 99 percent coming from its mother and father — but roughly 20 to 25 genes come from the donor’s mitochondrial DNA, ensuring the healthy genetic makeup of the child.

Tayla Robichaud, a 21-year-old Billerica resident who was 18 years old when her physicians began diagnosing her energy deficiency as mitochondrial disease, said she is a proponent of the technology.

“Junior year, I missed about 80 days of school and senior year, about 100,” she said. “I always thought that I would never be able to have kids because I would never want to give them this horrible disease. Having the possibility to actually have kids without them being sick is amazing.”

Robichaud said she faced a fair amount of adversity in her battle with mitochondrial disease. Often times, she said, her mother was the only person in her life who believed that something was genuinely wrong with her — others simply mistook her energy-deficient cells for laziness or a lack of drive. She said she has tried her hand at a number of jobs, but her mitochondrial issues have manifested themselves in postural disorders, which render her unable to remain on her feet for any significant period of time. One solace for her was involvement in support groups and communities that allowed her to share this adversity with other young adults affected by the disease. Her second cousin is getting tested for the disease, she said, and they have been able to discuss the process together.

Devin Shuman, a 22-year-old sufferer of mitochondrial disease living in Seattle, has played a role in the continued existence of groups for people like Robichaud who are looking to have their experiences validated. Shuman, whose brother also has a mitochondrial disease, attended a medical conference put on by the United Mitochondrial Disease Foundation in Chicago the summer after her diagnosis and soon became an ambassador for the group.

“For me, meeting other teenagers honestly completely changed my perspective on this,” Shuman said. “I honestly can say that my life changed when I went to that conference. A lot of teenagers are the only person they know with this … it really helps when you have other people to talk to because you can discuss the weird thing that happened to you or the new thing you’re dealing with, and you get a dozen people responding.”

Shuman said experiences like Robichaud’s are commonplace in the sphere of mitochondrial diseases and that she hopes to alleviate them through her work with the foundation.

When discussing the finer points of the disease and the three-parent child initiative as a means to curb it, the conversation is relatively straightforward. When ethical questions come into play, though, things can begin to get muddy.

“We teach about reproductive technology in our class, but in general, a lot of people have thought that this hinges not so much on the technology, but the motivation,” Steffen said.

Not everyone is so keen. Human Genetics Alert, an independent UK watchdog group that focuses on genetic research, has come out in vocal opposition to mitochondrial replacement. The group said it fears that the technique would set a precedent leading to the normalization of “designer babies” that are developed and selected for their specific genetic traits.

Rabbi Benjamin Samuels, a student in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, is studying the three-parent child initiative and mitochondrial replacement as it intersects with Jewish law. While he said he acknowledges the situation’s inherent ethical complications, he nonetheless feels that responsible uses of mitochondrial replacement pose no major religious or ethical violations, though they do pose interesting questions about Jewish lineage.

“Although I think Jewish bioethicists would agree that there needs to be supervision and regulation, Judaism is in favor of stem cell research, would even support cloning if there was a therapeutic need and much of the new reproductive technologies, including three-parent children,” he said.

Though Samuels understands concerns like those of the Human Genetics Alert — he calls their stance the “slippery-slope argument” — he is confident that modern medical professionals are able to draw their own line in the sand when it comes to genetic manipulation.

As for Robichaud, she said she doesn’t have the utmost faith in her own country’s ability to take a cue from the UK’s decision. Nevertheless, she has a few words for those worried about research spiraling out of control.

“I know people who have mitochondrial disease and whose kids have it,” she said “What would we rather have: kids dying and living horrible lives, or having healthy children and a healthier population?”