The Office of Workforce Development and the Boston Redevelopment Authority released a labor report Tuesday that showed an increase in income inequality and the cost of living in the city despite an unemployment rate of 4.3 percent, according to a Tuesday BRA press release.

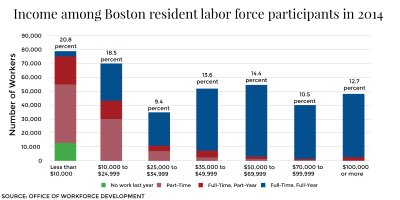

The release stated that the median wage for Boston residents has remained stagnant for approximately three decades at $35,273. Also according to the release, the report also shows that around a quarter of Boston’s fully employed workers take home less than $35,000 a year, and those who commute into the city for work make 8 percent more than residents.

Trinh Nguyen, director of the Office of Workforce Development, said Boston’s problem of inequality has been developing for many years now.

“As far as how Boston reached the present state, what you see is systemic problems accumulated over time,” Nguyen said. “Access to public education, gentrification, standards of living, housing, wage disparity and a compounding legacy problem is at play.”

Nguyen said that though the findings of the report were alarming, long-term economic growth has been and will continue to be a priority for the current administration.

“The report reflects an alarming national trend, and that is why the administration commissioned this report, to look more closely and dive deeper into the data,” Nguyen said. “Instead of only short-term outcomes, the administration plans on emphasizing a long-term strategy.”

Nguyen also talked about other measures the city is taking to assist entry-level workers and the factors that contribute to the current income inequality.

“The second step the administration is taking is to meet with intermediary workforce agencies and ask them to work with entry-level workers and provide additional training and the opportunity to ‘learn and earn,’” Nguyen said, “where they earn enough to live and take care of their families, but they can also earn community college credits towards an associate’s degree to post-secondary education.”

Madhu Dutta-Koehler, a professor in Boston University’s Metropolitan College, supported the recommended approach of emphasizing long- and short-term job stabilization and talked about the potential pitfalls of relying solely on the report data.

“In terms of the job income disparity, if you include at all the students who are really a migrant population, then the income disparity looks to be a lot more than it is for the stable population of Boston,” Dutta-Koehler said. “So that is something that needs to be underscored when those statistics have been used to create a case — that there is so much income disparity.”

Dutta-Koehler also discussed the actions the city will take in response to the new findings.

“The report states a few things that the city plans on doing in response to the report, one of them being that the city is going to hike the minimum wage to $11, and there is going to be a renewed sort of developmental emphasis on quality, affordable housing,” Dutta-Koehler said. “A two-pronged approach is necessary, where you stabilize the jobs at the lower end and at the same time, work towards creating an upward mobility.”

Several Boston residents shared their opinions on the city’s current labor condition.

Meredith Wood, 41, of Brighton, said gentrification plays a role in Boston’s income inequality.

“It is safe to say that gentrification comes from an increase of service jobs and not necessarily an opportunity for higher-paying jobs,” she said. “That’s the benefit and drawback of living in a city that people want to live in.”

Patrick Walsh, 30, of the South End, said the problem cannot be solved by one group.

“The solution is not as cut and dry as just, ‘One group needs to do something,’” he said. “If you’re talking about a younger population, the colleges also need to play a role in this discussion. The city has to reform housing in a way that will create more affordable housing so college kids will invest in housing and therefore invest in the city itself.”

Christopher Possinger, 33, of Jamaica Plain, said housing prices play a large role in driving businesses out.

“I think that the price of real estate has gotten too high in this city, and the BRA has been really slow about opening things up for more affordable housing,” he said. “It makes it harder for businesses to stay that need lower rents like bodegas and little restaurants, because all of their money is going towards rent.”