Getting a college degree may no longer be a source of economic mobility, according to a new study conducted by two City University of New York scholars. The study shows that after graduation, students from low-income families may be less successful than students from higher-income families, even if they go to the same school.

Research by Dirk Witteveen, a doctoral candidate in sociology at the Graduate Center of CUNY and Paul Attewell, a professor in sociology also at the Graduate Center, tied the burdens of college loans and fees to the economic background of students’ families.

The study adjusted for certain factors, such as excluding people who were unemployed for 10 years out or dropped out of college. Researchers also look at other factors such as major and academic performance.

They found that college graduates from low-income families earned around 12 percent less than their higher income peers, with a median income of $57,000.

The study’s result was met with controversy and skepticism, for its direct contradiction of another study on the same subject. Another report, conducted by the National Bureau of Economic Research, said that college acceptance was indeed helpful to “economic advancement.”

Evgeny Lyandres, a professor of finance at Boston University, wrote in an email that there were possible margins for error in the study.

“It does not control for race, which may be related to post-graduation earnings, and this omission makes the conclusion that wealth on its own affects post-graduation earnings less reliable,” Lyandres wrote.

However, he also added that no matter the results of the study, he found the issue it tried to address in college income inequality relevant, and could possibly be remedied by Witteveen and Attevell’s suggested solutions.

“If the problem of persistence of inequality post college indeed exists, I think that the remedies proposed in the article — training in financial literacy and public speaking — could indeed alleviate the income gaps among college graduates,” he wrote.

BU spokesperson Colin Riley said there were also issues with the way the study was conducted, that it should not have pulled from “more than one singular school,” but expressed confidence in BU’s positive impact on all students, regardless of income.

“I think in my own experience, there is data that can help you understand the benefit of a Boston University degree for all graduates,” said Riley. “They end up in careers that allow them to repay those loans over that period of time.”

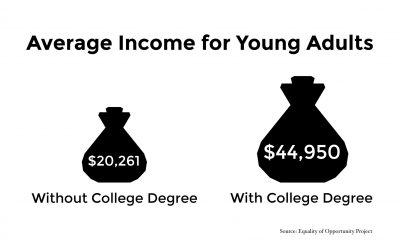

The study did however show that those who graduated college made significantly more than their peers who did not attend college.

“[V]irtually every study shows that the lifetime earnings of a person with a college degree is significantly higher than someone with just a high school education,” Riley said. “Now, going to college isn’t all about lifetime earning … But certainly, you want to be sure that if you do borrow money, you want to be able to repay those loans. So, it reflects well on our students.”

Several students said they believed other factors could have been at play in the study as well.

Skye McKay, a sophomore in College of Arts and Sciences, also believed that family connections and the ease of the job were different for students with differing incomes.

“People with a higher income, their families have higher incomes so their families know more people and they get more job opportunities,” McKay said. “Whereas with a lower income, you can’t just ask your uncle who knows this company for an internship. You gotta actually work to find it.”

Grace Jeffrey, a senior in CAS, also said that she saw the potential of a low-income background hindering a college student’s success in her personal experience with balancing work and school in order to satisfy loan and scholarship requirements.

“There’s definitely an accessibility gap between families that make a lot of money, and families that have a lower income,” Jeffrey said. “From someone who has a lot of loans, having to do work, on top of school to pay for add-ons, like going out with your friends and also just making sure you meet your scholarship requirements … can add a lot of stress and is time consuming.”

Meghan Garrity, a freshman in the School of Education, said these inequalities are less common at BU.

“But I think at least at BU, for the most part, people have equal opportunities because you don’t really have to like, pay to join clubs or do anything,” Garrity said. “I think the only thing that people who are from a wealthier background might have an advantage with is housing or dining plans or sororities and fraternities.”