Space scientists have encountered several huge, unexpected solar flares over a short span of time this past week, one of which even resulted in a coronal mass ejection in the direction of the Earth.

Early on Sept. 6, the sun reached the solar minimum, the lowest point of solar activity in the star’s near 11-year cycle. However, this cycle’s minimum produced dispelled magnetic material that affects us here on Earth.

“When sun spits this stuff out, it needs to be directly in line with the Earth in order to impact us because the Earth is very small as compared to the sun,” explained Meers Oppenheim, an astronomy professor in the College of Arts and Sciences. “But if it doesn’t directly come in the direction of the earth it’s like a hurricane that missed us.”

However, the magnetic “hurricane” that did hit the Earth last week created a severe magnetic storm that knocked out all radio communications for about an hour across all the areas that were facing the sun at that point.

According to National Geographic, “a powerful CME can trigger a geomagnetic storm, which can disrupt satellites, GPS navigation and the power grid but can also spawn especially brilliant auroras.”

The ejection involves the sun spitting out a huge amount of material that is magnetic in nature and expelled in extremely large quantities.

“That material will take about three days to reach the surface of the earth,” Oppenheim said. “Once it does, it causes the magnetic field around the earth to flex and change its configuration and in the process it can create problems with our electric system and knock out several forms of communications.”

Even though it does affect communications, “they’re not really a big danger to us here on the ground,” he explained.

The solar flares that accompanied this are not a danger and routine, said Jeffrey Hughes, another astronomy professor in CAS.

“We’ve had two large flares in the last week or so,” he said. “They are not on a historical scale, they are not unusual but these kind of flares happen once in every 11 years or so.”

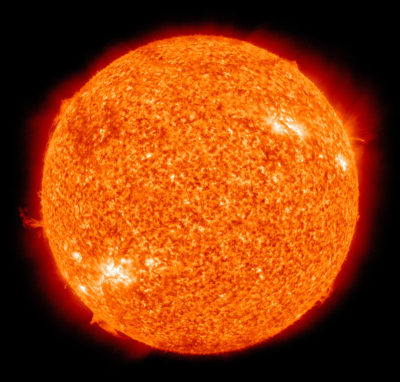

He further explained that since the sun was a magnetic star, it had magnetic fields, generated in the outer region of the sun’s interior that was convecting. This convective motion can occasionally twist upwards in some places and amplify the magnetic field.

The strong parts of these magnetic fields can come out of the sun in small areas called sunspots, which store energy that snaps and releases either a solar flare or another accompanying phenomenon called coronal mass-ejection.

Hughes further explained how, while the solar flares seemed like a big deal because the sun was so close to its solar minimum right now, it still did happen at times while the sun was cooling down.

“It’s really fascinating because we haven’t had a solar flare of this intensity in a little over 10 years,” said Zachary Orent, a senior studying physics in the CAS and the president of the Boston University Astronomical Society. “Not only that, over the past seven days we’ve had seven different solar flares.”

Orent was excited about the prospect that his first club meeting of the year would have so much to discuss and he explained how the club intended to try to observe any further activity that may occur on the sun.

JI • Sep 14, 2017 at 1:00 pm

Well this seems a bit odd that this article mentions that solar minimum occurred on Sept 6. The solar cycle is still on the downswing and we really won’t know when minimum has occurred until months after the fact.