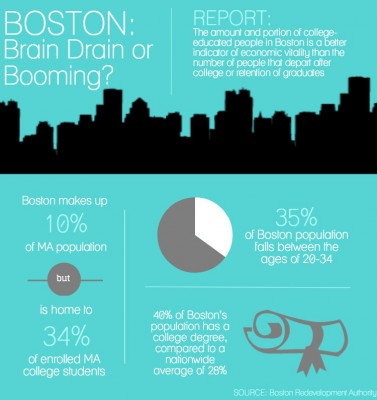

The number of college-educated people in Boston is a better indicator of economic vitality rather than the number of people that depart after college or retention of graduates, according to a Monday report by the Boston Redevelopment Authority and University of Massachusetts Donahue Institute.

The report, titled “Retaining Recent College Graduates in Boston: Is there a Brain Drain?,” claims by emphasizing on the mass exodus of college educated workers and retention of graduates out of the city, it is easy to miss the bigger picture that Boston has a high share of well-educated professionals.

“What we are saying is that none of that has a direct relationship with why people don’t stay here,” said Alvaro Lima, the director of research at the BRA. “They don’t stay here because they cannot find a job here. They cannot find a job here because the market is not large enough to accommodate every graduate that graduates each year.”

Boston comprises 10 percent of Massachusetts’ population, yet it houses 34 percent of the Commonwealth’s total college enrollment, according to the report.

Boston is also known as a young city with 35 percent of its population between the ages of 20 and 34, a percentage that only a few metropolitan cities come close to sharing, the report stated.

Nicholas Martin, spokesman for the BRA, said a significant percentage of educated-workers in Boston could lead to a more creative and active city.

“Given the fact that the group of recent graduates represents the highest percentage of the population, the highest in any American city, it’s tough to say what it would look like if we retained even more,” he said. “You can already see the benefits…in terms of the start-up economy [and] entrepreneurial efforts that go into Boston.”

Kevin Lang, a professor of economics at Boston University, said claims about brain drain in Boston are surprising, given the large influx of students.

“One of our big industries is education, and we export our product to the rest of the country,” he said.

Although Boston attracts many talented people, Lang said the city cannot possibly retain all of them.

“Look at the size of our college population and the size of our metropolitan area,” he said. “At a certain point, there just isn’t the population base or the employment base to support the number of highly-educated young adults.”

Several students said they were concerned about the prospects of finding a job after graduation, and they are not sure whether they will stay or leave at the conclusion of their academic careers.

Laura Cohen, a junior in the College of Arts and Sciences, said while she does not have any definite plans for after graduation, leaving the city can serve simply as a change of scenery.

“I really like the city, and I think it would be a good place to live after college,” she said. “[But] it would make sense that after being in a city for four years, you would want to go somewhere else.”

Chloe Lam, a junior in the School of Management, said she plans to take advantage of what Boston has to offer.

“There are a lot of great opportunities in Boston,” she said. “There are a lot of global companies that are around here, and I just think there a lot of opportunities as well, and it’s a great place to find connections and network.”

Michael Sciortino, a junior in CAS from New York, always planned to move back home after his undergraduate years to continue his career path.

“I know that Boston is more than just the colleges, but if you graduate college and you are still hanging around, you are not really accomplishing anything,” he said. “I just think there are other opportunities, and staying here after college, not to call it a dead end, but there are other opportunities out there. And I’d rather see the world rather than stay where I am now.”

Gabriella Arriaga, Paige Smith and Monika Nyak contributed to the reporting of this article.

Vice Chairman and archives keeper for The Daily Free Press Board of Directors. Former news editor. I like data, politics, and higher education, but will write about anything.