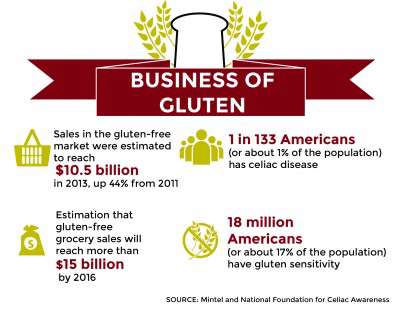

Gluten, the protein composite that everyone loves to hate, has proven to be lucrative for businesses as more restaurants offer food that excludes wheat, barley, rye and wheat-rye hybrid triticale. Businesses directly addressing the gluten-free diet have spawned from consumer demand for all things gluten-free. By 2017, the market for gluten-free food and beverages is expected to exceed $6.6 billion, according to research from Packaged Facts, a market research company specializing in food-based sectors.

Two Boston University students have decided to capitalize on the increasing need for dietary customization with a new technological advancement.

“What really brought it [dietary restriction] to my attention was when I came to Boston University my freshman year. I went to the dining hall at 100 Bay State and saw the gluten-free station,” said Jessica Morin, a junior in the College of Communication.

Morin and her colleague Rachel MacDonald, a COM junior, decided to tap into this need for dietary accommodation with an app that will be installed in food trucks around the city. The app will allow customers to create profiles that save their dietary restrictions and help food establishments identify those customers.

“It’s more effective to have an order written down through the app, so you can see it as opposed to having to say it,” MacDonald said. “That can easily be forgotten, misheard or misinterpreted.”

MacDonald said the idea for the app stemmed from personal dietary matters.

“I have a lot of allergies, so from that standpoint, I can totally understand the need for something that can cater to restrictions,” she said. “It is a serious thing, whether it be an allergy or a preference to choose gluten-free food. It needs to be taken seriously and accommodated to in all situations.”

The number of people who need or want a gluten-free diet seems to only be expanding, MacDonald said.

“Everyone seems to be moving toward a healthier lifestyle, whether it be for their needs or just for the want to follow this health trend,” she said. “It’s good to be healthy.”

Vegan ice cream café FoMu, with locations in Allston and Jamaica Plain, has a variety of gluten-free options on its menu, including unique flavors such as avocado, rosewater saffron and Thai chili peanut.

Catherine Davidson, retail manager of FoMu in Allston, said establishments that cater to those with dietary restrictions have been able to make a real difference in people’s lives.

“I had one girl in tears, and she came around the counter and said ‘I can’t even explain to you how much this place has changed my life,’” she said. “FoMu had changed her relationship with her friends and her husband because she was able to not feel left out eating out because she had a specific dietary need.”

FoMu is able to accommodate those with restrictions because they make its food from scratch, Davidson said, which allows the company to better understand its ingredients.

“We have a more hands-on approach because we truly care and try to be as transparent as possible,” she said. “We make everything in small batches.”

As someone who works closely with people on a gluten-free diet, Davidson said she isn’t able to pinpoint one reason why so many people are eliminating the protein composite from what they eat.

“There’s a few reasons why people would choose a gluten-free diet,” she said. “Some are diagnosed by their doctor to stay away. Some go through a transitional period where they are trying to figure out the source of their health problems. It’s hard to say. I can’t really speak for people’s personal decisions.”

But Davidson said she isn’t sure that gluten is as unhealthy as people often make it out to be.

“Who knows if gluten is as bad as they say? For people with serious diseases, that’s clear [that it is bad],” she said. “[But] there’s always something that the media and professionals deem bad, and I think that moderation is key.”

Some students said they don’t see the need to stop eating gluten for non-medical reasons.

Jack Knollmeyer, a sophomore in the College of Engineering, said he sees no need to adopt a gluten-free diet.

“It’s popular because people assume that [gluten]-free means something unhealthy has been removed and therefore is healthier, even when gluten-free isn’t any healthier for people who don’t have an intolerance or celiac disease,” he said.

Knollmeyer said he is skeptical about going gluten-free.

“I don’t eat gluten-free because I don’t have celiac disease or an intolerance [to gluten],” he said. “It doesn’t make sense to needlessly restrict my eating options.”

CORRECTION: A previous version of this article identified Rachel MacDonald as Rachael MacDonald, a graduate student in the School of Medicine. The article has been updated to reflect this change.