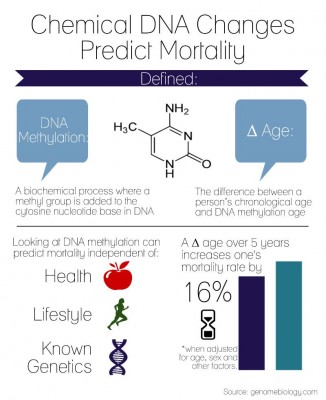

Biochemical changes in DNA may be able to predict biological age, according to a study released Friday in the journal Genome Biology.

The study found that DNA methylation, a biochemical process where a methyl group is added to the cytosine nucleotide base, serves as a biomarker for chronological age, said Kathyrn Lunetta, study research manager and a professor at Boston University’s School of Public Health.

“We call this difference delta age. What we wanted to know was whether this difference was a good predictor of future events, such as death,” she said. “Everyone dies at a different point and different age, and what we may be able to look at here is to use the DNA methylation to get a better predictor how someone is aging or how well someone is aging.”

Lunetta said DNA methylation may be a better predictor of how well individuals age.

“What we found was that in all of the studies, we were seeing an increased risk of mortality for every five-year larger difference in age, delta age, compared that to the chronologic age,” she said. “If their delta age is negative, that means they are ageing more slowly and have a longer period of time looking forward that they will remain healthy than their chronologic age would suggest.”

A delta age greater than five years increases mortality rate by 21 percent with age and sex taken into account, according to the report. When adjusted to account for demographic and risk factors including whether a person smokes, how much education they have or whether they have high blood pressure, the mortality rate is 16 percent.

Data from several cohort groups of study participants from the United States and Europe were used collectively to determine the differences in delta age and see the ways delta age predicts mortality, the report stated.

Researchers from universities in Edinburgh and Queensland, the National Institutes of Health and several schools including Harvard and Johns Hopkins universities worked on the study.

Lunetta is involved with the Framingham Heart Study, which is one of the cohorts that researchers have worked with. Large collaborative efforts such as this are becoming more commonplace in research, she said.

“The study was a collaborative effort between several different studies. This is quite common in genetics and genomics now. Different studies have to combine their data in order to have enough information to identify these types of associations,” Lunetta said.

Several students said it was interesting to hear about groundbreaking research that BU professors are involved in.

Christina Mazzio, a freshman in the College of Communication, said research like this can be used to discover new solutions and prompt insight inside the classroom.

“I guess it’s good because the professors can create a connection to students about important scientific investigations and studies, and they have inside knowledge about it and the process of researching,” she said.

Kelly Huynh, a senior in CAS who is studying biochemistry, said looking into DNA for the study can present invaluable information.

“Sometimes, some people think that people aren’t ready to know what their DNA can tell about them, but I think it’s a positive thing actually. If you’re able to look into someone’s DNA and be able to foresee a lot of things, then it opens many options for preventative care,” she said. “There’s definitely a lot more to gain than there is to lose.”