In 2013, China’s president proposed a project — the Belt and Road Initiative — aimed at promoting the economy, allocating resources and connecting countries in Asia, Europe and Africa.

In 2017, the initiative resulted in the country spending less money toward energy projects but increased the total amount of projects it invested in. Researchers at Boston University’s Global Development Policy Center say that while the demand for energy access and infrastructure exists, the drop in money invested in these projects may be an indicator that China is moving away from riskier investments.

Xinyue Ma, a China researcher and project leader with the GDP Center, said the initiative does not solely include energy projects, but also other infrastructure projects like transportation, industrial park projects, overseas investment in other countries and infrastructure connectivity within China, Ma wrote.

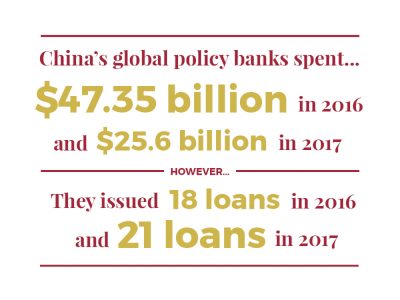

China’s global policy banks, which allot loans to several countries across continents, spent 54 percent less in 2017 than it did in 2016 — $25.603 billion compared to $47.353 billion. However, the banks issued only 18 loans in 2016 compared to 21 in 2017, according to the researchers’ policy brief.

“China has already invested in a portfolio of projects with higher risks than the commercial banks and most multilateral development banks,” Ma wrote in an email. “We may interpret this drop as China’s development banks becoming more risk-averse.”

William Kring, the assistant director of the GDP Center, said the process of collecting the data for the study took place over the course of an entire year and involved rigorous methodology to ensure all of the data was collected and verified correctly.

Because the China Development Bank and Export-Import Bank of China do not make the figures public, Kring said, researchers rely on manually validating public data gathered from articles in both the Chinese press and the press in the countries receiving the loans.

“You hear about proposed projects, you hear about agreements to move forward with a project, but there’s no actual loan they’ve issued yet, or the project hasn’t broken ground yet,” Kring said. “So, we try to be really rigorous in identifying loans that are in that present year.”

Kring said one of the most significant findings from the study is that the majority of China’s financing was in the power generation sector, with large increases in hydroelectric power and a decrease in the number of coal projects.

The data collected in the study can be used by others who rely on information about environmental, developmental or economic impacts of global policy, Kring said.

He added that scholars, researchers and policymakers are trying to see where China is making its energy investments, and through this research, a clearer picture of the Belt and Road Initiative is made.

“There’s lots of ways that this research can then act as a stepping stone for others,” Kring said. “I think that if you’re concerned about the environment — if you’re concerned about where energy investment is happening in the developing world — then a tool like this is really useful in seeing where those energy investments are happening.”

CORRECTION: A previous version of this article stated that China’s global policy banks spent $47,353 in 2016 and $25,603 in 2017. In fact, they spent $47.353 billion in 2016 and $25.603 billion in 2017. The article and the accompanying graphic have been modified to represent the true spending of the banks.