For centuries, people have wondered about the smile on the face of the Mona Lisa, one of the most well-known works of art on the planet. Why does it sometimes seem to disappear, only to reappear seconds later? Could she be alive? Or could it be something else — something intrinsic that says more about us than it does about her?

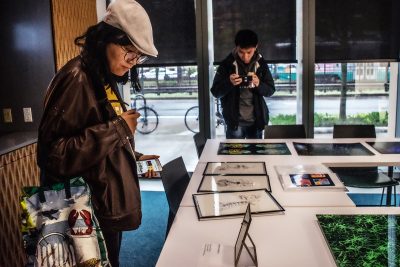

Questions like these were posed — and some were even answered — at the annual NeuroArts Forum at the Rajen Kilachand Center for Integrated Life Sciences and Engineering on Oct. 11.

Margaret Livingstone, a neurobiology professor at Harvard Medical School and one of the four speakers at the Forum, said the answer to the Mona Lisa’s elusive grin lies in a person’s ability to perceive the world around us.

Mona Lisa’s smile changes based on where you look, Livingstone said at the Forum. When one’s eyes focus on one area for too long, a different area begins to fade.

“Your central vision is good at high resolution processing,” Livingstone said, “[While your] peripheral [vision] is better at full image low resolution.”

Even though Greek philosopher Aristotle created a division between science and the arts, Postdoctoral Research Associate at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Praneeth Namburi, himself a dancer, said at the Forum the arts are important in scientific function.

“The way you look at the brain constrains the way you think about it,” Namburi said. “Dancing gives you a way to look at or investigate something without any preconceived notions.”

Kim Zak, a senior pursuing a dual degree in the College of Fine Arts and the College of Arts and Sciences, attended the event and said she believes that her interdisciplinary studies in painting and psychology reinforce one another.

“I think that my studies in psychology contribute to and enhance my studio practice,” Zak said. “And likewise, my fine arts education helps fortify my understanding of the important roles art plays in the way we understand the world.”

While some spoke about how science and art can complement one another, Psyche Loui, assistant professor of creativity and creative practice at Northeastern University spoke at the Forum and said she believes art and science are both enjoyable endeavors to be appreciated on their own.

“Improving cognitive health shouldn’t be the only reason to fund art,” Loui said.

Art is something that should be done purely for the love for art, — “art for art’s sake,” Lou said.

Zak said she believes her love of painting and psychology stems not just from their important combination, but also from a gratification obtained individually by both.

“There’s also the personal element,” Zak said, “which is that I couldn’t really picture myself just pursuing social science or just pursuing fine arts and feeling fulfilled.”