In the modern world, women have grown up with the idea that they can have it all: motherhood and a full-time job. While this may sound like the bare minimum, it has only been recently acceptable for women to pursue a career.

It wasn’t until the 1990s that 74 percent of women between the ages of 25 and 54 were in the workforce, compared to the 93 percent of men in the same age range. It has stayed around this percentage since then.

Even though working women are normalized, it often feels like a mandatory choice between motherhood or having a career. Women are still expected to do most of the housework and child care regardless of how many hours they work.

Women who work long hours outside the home face the stigma of being bad mothers for not spending more time with their children. But when men do the same, they’re just considered hardworking.

Women are also paid less for the same work. In trying to understand why, recent studies have linked the gender pay gap to motherhood.

The pay gap increases later in life when women get married and have children. The traditional gender stereotypes and biases that come along with these life choices can cause women with children to lose out on further responsibilities because of their employer, or receive a lower salary.

While many women continue to fight against these stigmas, inequality persists in the workforce. In the United States, women face obstacles, such as unsubsidized and unaffordable child care and practically non-existent paid maternity leave.

Unfortunately, these workplace disparities have only been exacerbated by the pandemic.

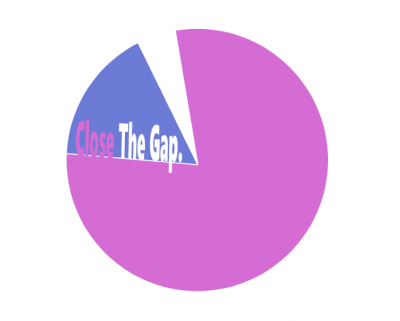

As child-care options completely disappeared and school became virtual, unemployment for women skyrocketed. In the U.S., women make up 43 percent of the workforce and an astounding 56 percent of job losses as a result of the pandemic, according to a report from McKinsey Global Institute.

We have seen many women choose to quit their jobs and sacrifice their careers to manage the incredibly difficult task of taking full-time care of their children when schools closed down.

Breadwinner mothers who can’t afford to lose their income are hit even harder. Not only do they have to work their full-time job from home, but they also are responsible for their kids during the workday. They cannot make the difficult decision to quit their jobs because their household relies on it.

But it isn’t just a setback on the individual scale — the choices these women were forced to make could unfortunately reverse decades of progress. If so many women are once again out of work, it will take time to return to the demographics of the pre-pandemic workplace.

The disproportionate number of women currently out of work could potentially worsen the negative bias against professional women and working mothers.

We need to have a serious conversation about why women are the only ones cornered into being a parent or having a job. If we as women truly want to “have it all,” men need to step up and make the same sacrifices and commitments for their families.

Progress can be made on the policy side as well — better maternity benefits, family planning, education and child care. All of these changes will help women across the world make strides in the workforce and push back against the gender inequality that continues to persist.