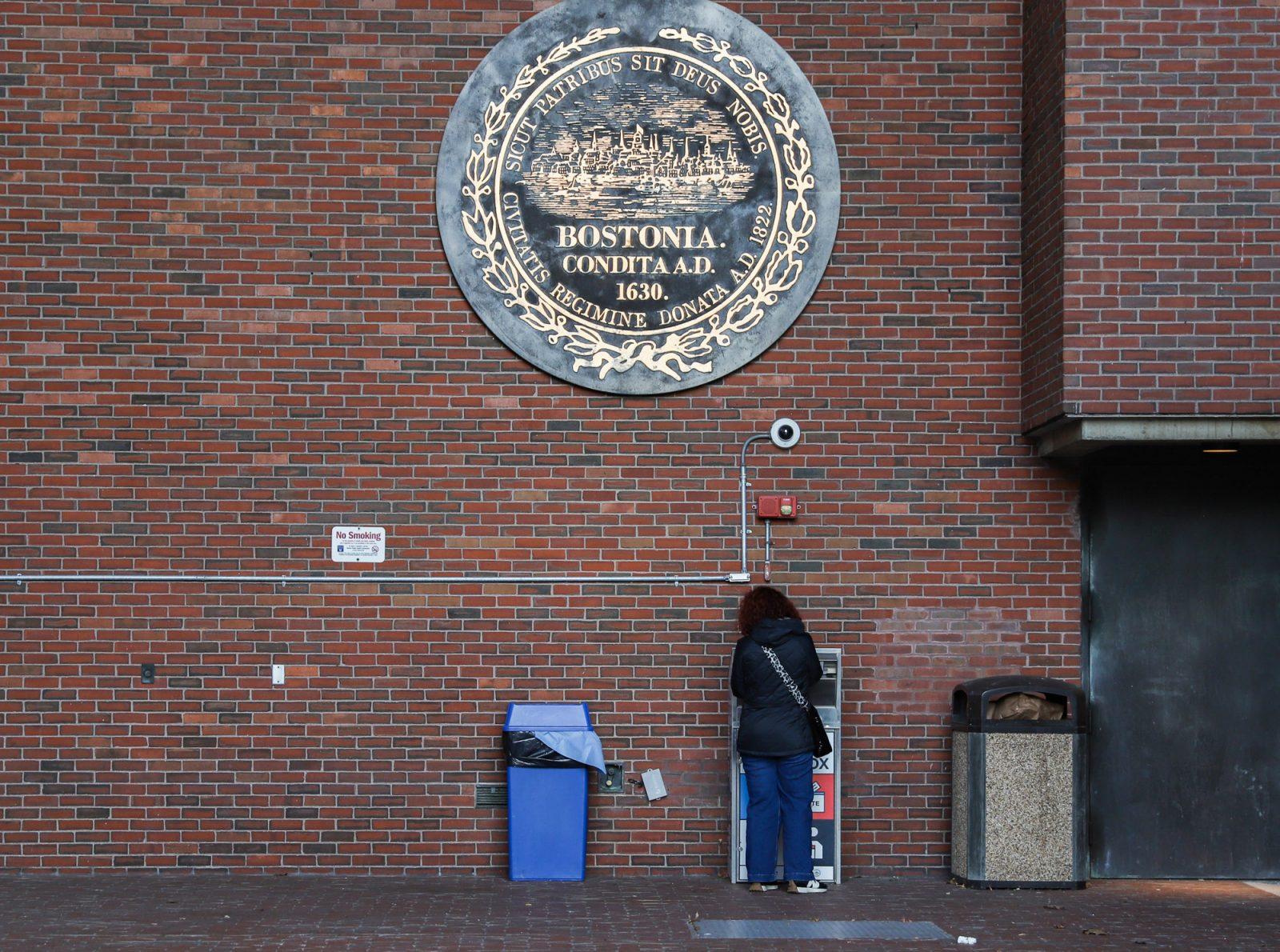

When College of Engineering sophomore Brian Zhou took over the @bostonu Instagram account Feb. 9., he shared his experiences and insight as a Boston University student with the page’s 118,000 followers.

But that same day, he also received a racist comment from a troll account.

Zhou responded to the comment on his personal account and addressed the wider issue of rising anti-Asian sentiments throughout the United States in a post that garnered nearly 2,000 likes and more than 500 reshares, he said in an interview.

“I didn’t expect it to blow up this much,” Zhou said, “but it shows that people are really affected by it. And they really see it.”

In his post, Zhou wrote how such remarks contribute to increased prejudice and hate crimes against Asian Americans.

“Comments like the one on my Terrier Tuesday Takeover may seem minor,” he wrote, “but they reflect a larger, pervasive culture of hate in the U.S. We must raise awareness and speak up and against violence and Anti-Asian hate.”

Between March and June of last year, more than 2,100 hate incidents were committed against Asian Americans — spurred by COVID-19 — according to a report released by the Asian Pacific Policy and Planning Council and Chinese for Affirmative Action.

Zhou said he didn’t want to assume the comment came from a BU student, but censored the username as a precautionary measure.

“All I know is it is a troll account, and that’s all we can assume really,” Zhou said. “I didn’t want to cancel them and I wanted to protect them too.”

Although Zhou was not as strongly affected by the comment — he has experienced racist comments throughout his life — he said he thought it was worth sharing because of this trend in overt racism against Asian Americans.

“I believe the underlying sentiment was due to something larger, which is due to the COVID-19 pandemic,” he said. “Many people are expressing more outwardly their deep-rooted racism towards Asian Americans and Asians in the U.S. and around the world.”

Zhou said he and his friends have noticed a change in attitude toward Asians since last spring. When Zhou flew home on a plane when the pandemic first hit, the experience was “frightening,” he said.

Zhou cited several factors that may have exacerbated the rise in anti-Asian sentiment, such as Orientalism — a colonialist representation of Asia that applies stereotypes — and a sense that Asian Americans are not seen as Americans.

However, Zhou said these beliefs, from his personal experience, are not as noticeable on BU’s campus compared to other places.

College of Arts and Sciences senior Vy Hoang said Asians experience race-based attacks differently, given the diversity within Asian identities.

“Anti-Asian racism definitely doesn’t manifest in the same way for everyone,” Hoang said, “because there’s so many different kinds of Asian people.”

Hoang said she typically experiences anti-Asian racism in the form of microaggressions and assumptions about her academic performance. She also added a broader issue was the fetishization of Asian women.

“Asian women are over-sexualized all the time,” Hoang said. “It’s really dehumanizing. I think, for a lot of people, they kind of whittle down what an Asian woman is supposed to act and look like.”

In general, Hoang said Asian stereotypes can make some “feel like you’re not your own person.” Hoang added that this racism is not new on campus.

“I think it would be a mistake to think or say that anti-Asian racism hasn’t existed at BU before this moment,” Hoang said.

She said the negative assumptions made about international Asian students on campus — such as their wealth or their supposed superiority complex — was one example.

Popular sentiment against China, Hoang added, was turning many Americans against Chinese people as a whole.

“I feel like the media plays a central role in basically convincing white Americans and Americans at large that China is this huge threat,” she said.

One New York news clip, in which a 93-year-old woman was attacked by two teenagers last summer, caught CAS sophomore Justin Kan’s attention for one specific reason.

“Interestingly enough, they did not mention at all that the victim was Asian,” Kan said. “Instead, they stressed that the neighborhood was a white neighborhood.”

Hoang cited media portrayals of Asian people as being responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic as another factor.

“Whenever they have any articles on coronavirus, I’ve noticed that they use pictures of Chinatown or ancient Chinese artwork,” she said, “and that says so much to me about the skewed sense of awareness of news media sources.”

To address biases on campus, Kan said he wants the University to first release an official statement and work with Asian student organizations to create resources for students to combat racism.

“Perhaps you could report instances of discrimination or racism, not necessarily for Asians, just in general of course,” Kan said, “because that’s a prominent issue that has been going on and will continue to go on if nothing is done about it.”

Michelle Nie, a sophomore in the College of Fine Arts, moved to the U.S. when she was five and said she has also experienced subtle racism — people would often make a “little, tiny, snarky comment on the side” and commit microaggressions against her when she was growing up.

Nie said she wants BU to do more than the minimum when it comes to addressing racism on campus — not just “empty promises”

“I don’t want an email, meaning I don’t want the University to be like ‘Oh, we stand with Asian Americans,’” Nie said. “What I want is a plan, like how are you going to tackle this issue?”

Making courses and other academic opportunities available for students at BU is one way the University can address racism on campus, Nie said.

“I never had an education for me to explore more about my ancestors and the Asian American experience here,” she said. “I think that’s very well needed.”

Hoang said she was critical of the BU administration’s lack of concern toward Asian students.

“One of the biggest obstacles for the safety and well-being and things of Asian people on campus,” Hoang said, “is to realize that the administration in the first place does not value Asian people.”

Hoang noted Asian cultural organizations do not have the administration’s ear nor support when it comes to initiatives they care about, such as creating an ethnic studies department at BU.

However, Hoang emphasized that dealing with anti-Asian racism should not be compared to other anti-racist movements.

“The one thing that cannot happen, that I don’t want to see happen, is people going ‘Oh, I wish that people would talk more about anti-Asian problems like they talk about Black Lives Matter,’” she said. “Those two things do not have to be compared like that.”

Individually, students should take it upon themselves to call out and correct racism when they encounter it in their daily lives, especially in the classroom, Hoang said.

“It’s literally as simple and as difficult as, in class, if someone says something, if a professor says something,” she said, “to be like ‘That’s not cool, that was actually super racist, and you shouldn’t be saying stuff like that.’”