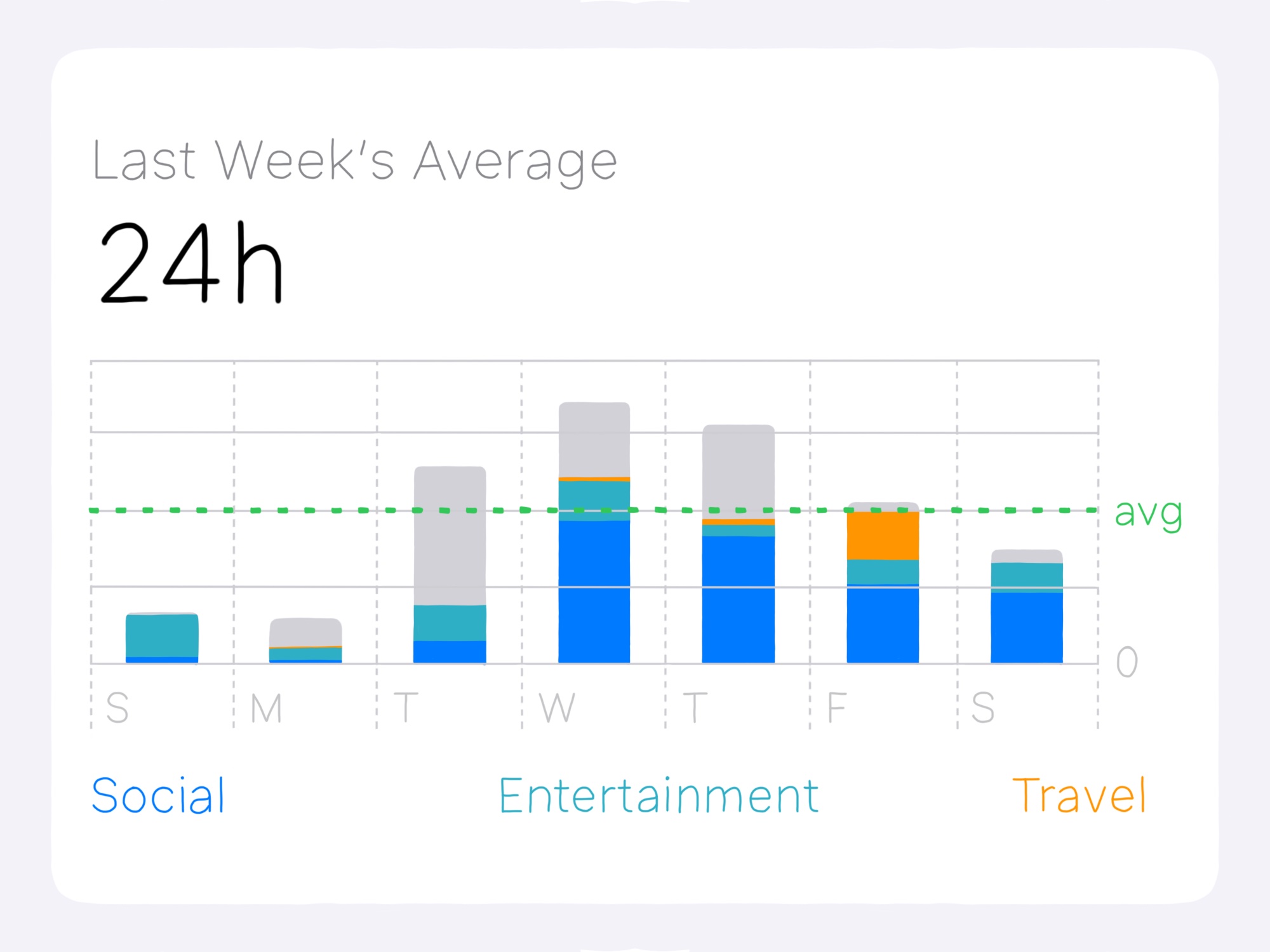

When Apple released the Screen Time feature in 2018, consumers rejoiced.

Finally, we could limit the amount of time we spend staring at an app, simply through having the data at our fingertips. Finally, we could limit disruptions and set time limits to keep the pesky algorithms away. Finally, parents could control their media-hungry teens.

Fast forward to the present day. It’s six years later and we still are grappling with the negative effects that too much screen time has on our physical, emotional and mental health.

A research study directed by the Yale Department of Psychiatry and Columbia School of Nursing in 2023 deduced that one-third of youth spend four or more hours a day engaging with their screens. The effects of such are great, leading to internalization and anxiety, among other things.

Was Apple not supposed to have already presented the solution to us? Did we rejoice too early?

Simply put, Apple’s Screen Time feature allows users and parents or guardians to place app limits on themselves and their children. These limits, easily bypassed by a four-digit code or a request sent to the parent, relied on the willingness of the participant to put the phone away.

The feature also includes a Downtime setting that regularly limits certain apps to be restricted for a period, presumably during one’s hours of sleep. Just last year, Apple added a Screen Distance feature, sending the user an alert when the iPhone is too close to one’s face, with the aim to reduce eye strain.

Apple is aware of the worsening effects that their devices have on impressionable, young teens. Their approach to combating these effects, as evidenced by their 2018 update, is restriction. The logic is that through making the apps appear unavailable or alerting the user of health risks, one’s sleep and one’s health should be improved.

These features and the data it offers to users is a step in the right direction. There is no denying that we live in a data-driven society, where human data has become a currency. We emphasize the value of numbers — quantitative, irrefutable facts. Yet, how often is this data questioned?

I open my settings app to Screen Time. Four hours and two minutes, it reads. Yet as I count the individual app usage — one hour and 12 minutes on Messages, 36 minutes on Instagram, 27 minutes on Safari, 10 minutes on Gmail — I see that something does not add up … literally.

Others are facing similar problems, and perhaps you are too. Back in August of 2023, Apple received backlash from parents and users claiming that the feature had major glitches. While iOS updates since then have made improvements, the problem still looms.

Yet even beyond the data inaccuracies, the entire premise of the iOS function — restriction and limitation — has failed. With the ability to bypass Screen Time, one more minute turns into unlimited access for the entire day.

Even further, the promise of healthy habit-building has been unfulfilled. The routine of checking how much time we spent on the New York Times as opposed to on Snapchat has overshadowed the habit of simply putting our phone down when we see we have hit three hours of screen time.

The past couple of years, with the pandemic and massive isolation that resulted, have only exacerbated these habits. New apps and tools have since been released, aiming to fix the problem that Apple could not.

Opal, deemed the number one Screen Time app, is charging customers almost $100 per year with the promise that distractions will decrease, productivity will soar and our wellbeing will simply be far better off.

Opal is promising exactly what Apple did back in 2018, aiming to confront the problem of mental health and technology usage with a language that we all speak: numbers.

Is it fair to say that Apple failed in its effort to contribute to the growing mental health movement? No, it is not.

Ultimately, Apple only presented us with a tool, not a solution.