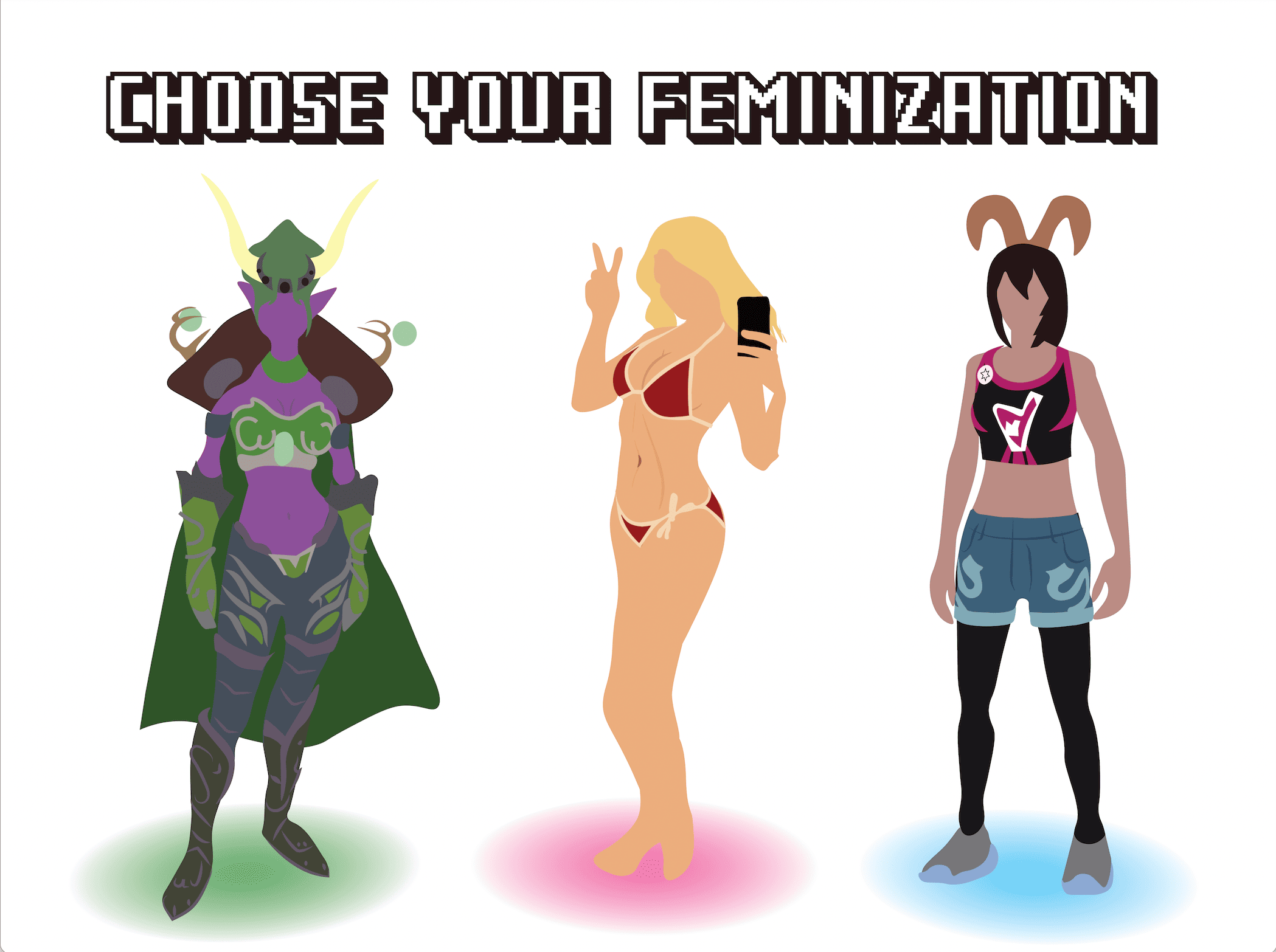

Hard-core, scantily clad women wielding giant swords. Tight tanks and dual pistols. Thighs that could crush heads like cockroaches.

These kinds of women are my heroes.

“Heavenly Sword,” “Tomb Raider” and “Street Fighter” are just a few video games featuring iconic female leads.

Nariko, the lead in “Heavenly Sword,” swings a sword bigger than her own body, and she does it with grace and silk-thin attire. “Street Fighter” character Chun-Li, the “First Lady of Fighting Games,” is known for her space buns, stockings and powerful thighs –– it is the essence of her fighting skillset.

Same goes for tomb-raiding archaeologist Lara Croft. The first iteration of her character showcased a disproportionate Barbie-like body, but subsequent games like “Tomb Raider: Underworld” make her more realistic, displaying her sexiness and confidence as a vital part of her character.

On Oct. 10, Netflix released the first season of “Tomb Raider: The Legend of Lara Croft,” a cartoon about the iconic character, who was first introduced in 1996.

IMDb gave the show 5.4 stars. IGN offered a 5 out of 10. Although Rotten Tomatoes gave it a 73% on the Tomatometer, more than 250 fans squashed that rating with a rotten 33%.

It’s boring, underwhelming and worst of all –– it completely changes Lara’s character.

While I would normally brush aside a screen adaptation, this one builds on and reshapes prior events in the franchise. “The Legend of Lara Croft” is supposed to piece into the existing lore surrounding Lara’s adventures, but it also brings forth an attempt to unify the character after 20 games released since 1996.

It’s confusing, too. The show is both a prequel to the 1996 games and a sequel to Lara’s Survivor Trilogy that debuted in 2013.

But the main problem is that the Lara we see at the end of the Survivor Trilogy is a shell of the Lara we came to love in old games like 2006’s “Tomb Raider: Legend” and 2008’s “Underworld.”

Netflix Lara and Survivor Lara have been criticized for constantly whining and crying, which might be fine for a character who isn’t the Tomb Raider. I liked the Survivor games, but that Lara didn’t have dual pistols or a sassy attitude –– assets that were once a staple of her character.

I’m not saying she can’t be vulnerable. In the 2001 Lara Croft movie, for example, Angelina Jolie was able to balance the character’s vulnerability and confidence at the same time. Modern Lara simply isn’t the Lara Croft we once knew.

But there’s another side to this.

People have also complained about Aloy, the protagonist from 2017-released “Horizon Zero Dawn.” Many have said she is too masculine or unattractive, which highlights an entirely different problem in society: hypocrisy in our desire for realism.

The difference between Aloy and Lara, however, is that Aloy was never a “Tomb Raider” kind of character. She wasn’t supposed to be sexy or conventionally feminine. She was brought up in the wild. She’s straight-forward, hard-headed and beautiful, and these attributes make complete sense for her character.

A character like Aloy should not be defeminized or over-sexualized just because it’s what developers think we want to see. It needs to make sense for the character. If a female lead is tough, hot-headed and wears full armor –– and that is in line with her character –– then that is perfectly fine.

But if she is sexy, biting and relentless, then by all means –– let that character thrive. Women want to be formidable leads, just like the Nathan Drakes and Joel Millers of the video game industry.

But we want to feel like women, too.

Researchers touched on this in a Sept. 10 study, “Examining How Sex Appeal Cues and Strength Cues Influence Impressions of Female Video Game Characters.” It found that while female gamers do not like highly sexualized characters, they actually prefer to play as them.

The study also delved into whether “portrayals of powerful characters may disrupt undesirable outcomes of sexual objectification.”

As a woman, I’d say that makes sense.

While video games like “SoulCalibur VI” do include overly sexualized female characters, the issue arises when the character is solely an object to look at, or when it becomes the character’s entire personality.

But for women in games like “Tomb Raider” and “Street Fighter,” power arises from their femininity.

An exposed midriff and a low-cut dress does not automatically mean a woman is being objectified –– if that were true, then I would never wear crop tops and cocktail dresses in real life.

By holding female characters’ femininity hostage, game developers are doing 45% of their customers a disservice.

Stripping a woman of her sexiness does not make her more human. If game developers want women to pick up the joystick and actually talk about their games, developers need to drop the politically correct act that cancel culture has snuck into the media.

It’s not about objectification, or thick thighs or big boobs and a pencil-thin waist. I’m not asking for an unrealistic Barbie doll as my protagonist.

We want personality, backstory and plain good characterization –– the abrasions that turned Lara into a cool-headed, gunslinging anti-hero, a pained purpose that forced Nariko to pick up a deity’s sword. If sexiness and a cool attitude comes with it, I am all for it.

Covering women up does not make them better characters or people –– and it certainly doesn’t make them feel seen.