When Jared Pincus was only a few years old, his father, Allan Pincus, fixed up an old computer and gave it to him to play with. Allan was mesmerized by young Jared’s ability to latch onto the mouse and enter the world of the games he played.

Allan wanted to join Jared in that digital world, but the computer games were all single-player.

“I remember saying to myself, ‘Why isn’t there a computer game that isn’t on the computer that we could all play together as a family?’” Allan said.

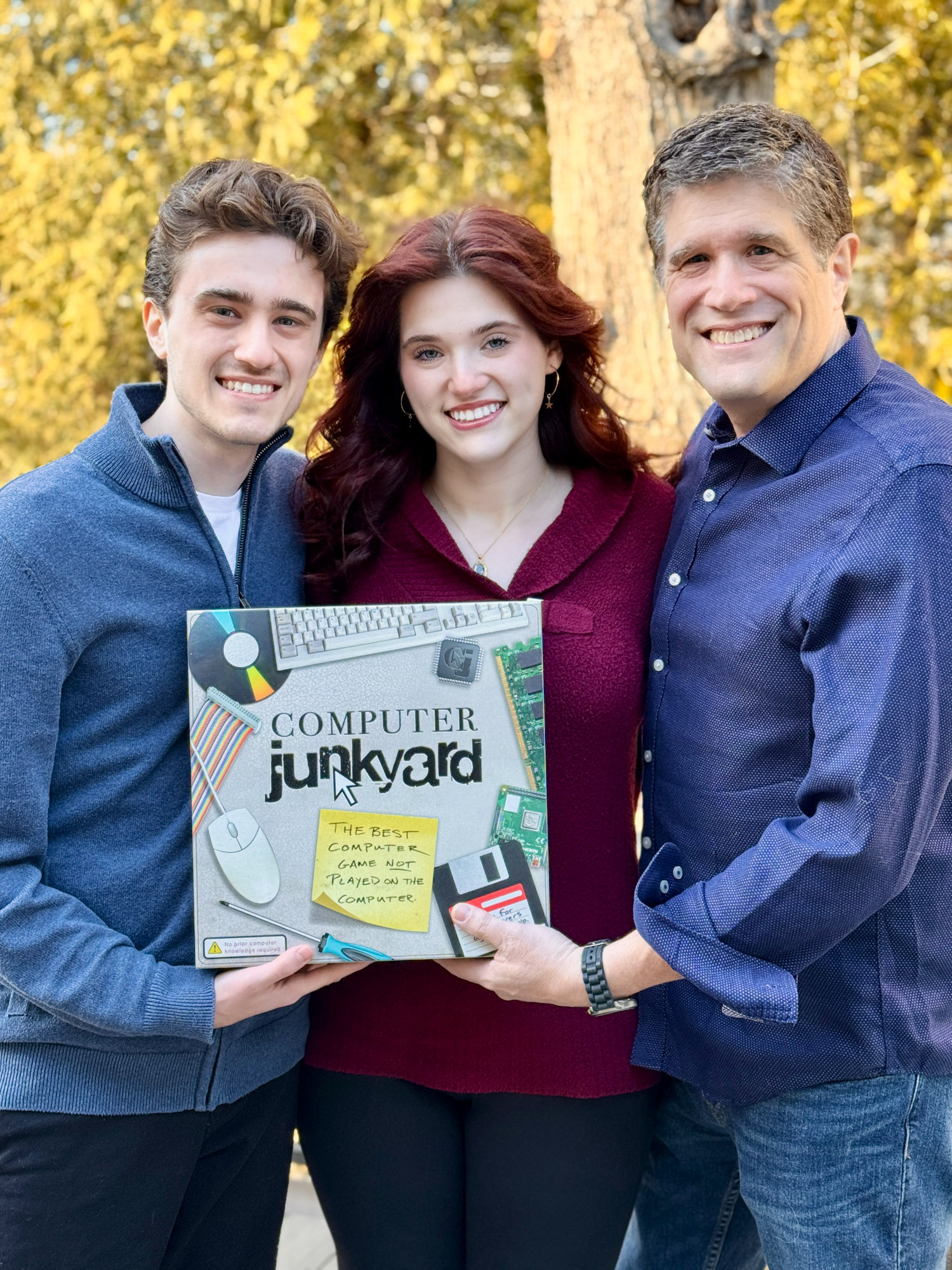

More than 20 years later, Computer Junkyard was born — with the help of Jared and Jordan Pincus, Allan’s daughter.

Computer Junkyard is an interactive, two-to-four-player board game where players race to build their own vintage computer out of spare parts found at a junkyard. Players must scavenge for parts, sabotage and trade with their opponents and manage their money — all with the goal of being the first to complete a computer.

Jared, now a third-year doctoral student in the Boston University Graduate School of Arts and Sciences computer science department, said Computer Junkyard was the culmination of a lifetime of collaboration with his dad.

“We were always working together on little toys and projects, building LEGO sets together, playing board games together,” Jared said. “The natural conclusion of it was this kind of project, to be working with him and to be working with my sister.”

While the family was on lockdown together during the COVID-19 pandemic, Jared pulled out one of Allan’s old Computer Junkyard prototypes and they began to work on it together.

“I am definitely my father’s son,” Jared said. “So much of [what I’ve done] was inspired by what he shared with me as I was growing up.”

Jared designed the “core mechanic” of the game — physical game tiles that interlock “like a jigsaw puzzle,” but unlike a jigsaw puzzle, they can be swapped and rearranged freely. Allan bought Jared a 3D printer, which Jared used to create prototypes of these tiles to play test with.

“We started assembling them with each other, and we went, ‘Oh, that’s really fun,’” Jared said. “From there, everything just snowballed, where surrounding that core mechanic, we just expanded on the idea.”

Earlier versions of Computer Junkyard involved more complex components of a computer — such as megahertz, gigabytes and wattage — which Allan said were removed for a more enjoyable game experience.

Originally, the objective of the game was to have the most leftover money after building the computer, which Allan said was less competitive because players would have to “wait around” for everyone to finish. He changed the game so that the first to finish building their computer wins.

“I just kept backing away, making it simpler and simpler and simpler,” Allan said. “The core fun was building the computer.”

Jordan, a junior at Carnegie Mellon University, said it was expected that she would design the artwork for the game, given her background in graphic design.

“When we had our first prototypes, Allan was making the graphics, and it was kind of understood from the get go that I would get to it down the line,” Jordan said. “We’ve always been a family of collaborators.”

Allan said he wanted the game box to look like a vintage computer, so Jordan implemented those elements into the design.

“The back of it has all the connectors, the front of it has a CD ROM drive and a grill where air gets drawn in [and] the bottom looks like the bottom of a computer,” Allan said while holding up the box. “Jordan did all that.”

Jordan also contributed to the logistic development of the game, with ideas she said were “spark lightning in a bottle.”

Early versions of the game used an eight-by-eight grid for players to build their computers on, but Jordan was the reason they changed it to a nine by nine grid, Allan said.

“We made it a nine by nine grid, simply because my daughter said, ‘I wish I had one more space,’” Allan said. “As much as Jordan says she was just doing the artwork, no, no, no, she’s been part of the creative process.”

The family refers to Jared as the “Chief Logician” as he was the point person for testing new ideas during the game’s development, using his background in applied mathematics and computer science. Jared said seeing the game develop over time was “astounding.”

“To go from play testing with something that you could tell was just this mock up, to then suddenly be play testing the next day with professional quality, beautiful tiles,” Jared said. “It made it feel so real, and it’s absolutely mind blowing.”

The family launched a Kickstarter campaign under their company, Dream Egg Games, to raise money to produce and distribute Computer Junkyard. They reached their $5,000 goal within five minutes of the Kickstarter launch, Jared said, and the game has currently raised more than $200,000 with more than 2,200 backers and eight days left in the campaign.

“So many people are chomping at the bit to buy their copy,” Jared said.

Allan worked with LaunchBoom, a company that helps creators build audiences for their products, leading up to the Kickstarter campaigns to ensure success. He said “hope is not a strategy for business,” but while he was aware of the work put in, he is still amazed by Computer Junkyard’s growing support.

“I did my homework. I knew entering the campaign that we had a success,” Allan said. “So, sure, where it is now, I had predicted this. I don’t know where it’s going.”

Most of Computer Junkyard’s followers are people of Allan’s generation who are driven by the nostalgia of the game, Allan said. The game is inspired by vintage computers from the 1980s to early 2000s, and the practice of putting together computers from spare parts.

“That’s the best thing we could ask for, aside from making a good game, is having it be emotionally resonant with people,” Jared said.

Jared aspires to be a teacher and said he is excited by the possibility of Computer Junkyard being a “learning tool to some extent” for those who are unfamiliar with computers.

“The idea that that could expose [non-computer savvy people] to some of those kinds of ideas, even implicitly, is also very exciting,” Jared said.

As an artist, Jordan said she wants consumers to be immersed in the board game experience.

“I want people to look at it and be like, ‘Yeah, that’s a board game,’ because it’s truly a style for board game design,” Jordan said. “It is definitely a really specific feel, so to capture that and have that as the end goal … is important to me.”

Allan said he hopes consumers enjoy the “world” he has created with Computer Junkyard, and he hopes to expand the franchise with a series of junkyard-themed games.

He could not have brought the game to life without the help of his kids, he said.

“I’m a proud dad,” Allan said. “This would not have happened without them, not in the same fashion.”