Being Brazilian, and more specifically being from Sao Paulo, I felt I had a patriotic obligation to watch and review esteemed Brazilian film and television director and producer Anna Muylaert’s latest film, “The Second Mother.” After all, it won the Panorama Audience Award at the Berlin Film Festival, and its main actress, Regina Casé, won the World Cinema Dramatic Special Jury Award for Acting at this year’s Sundance Film Festival, making it a must-watch for any Brazilian film lover.

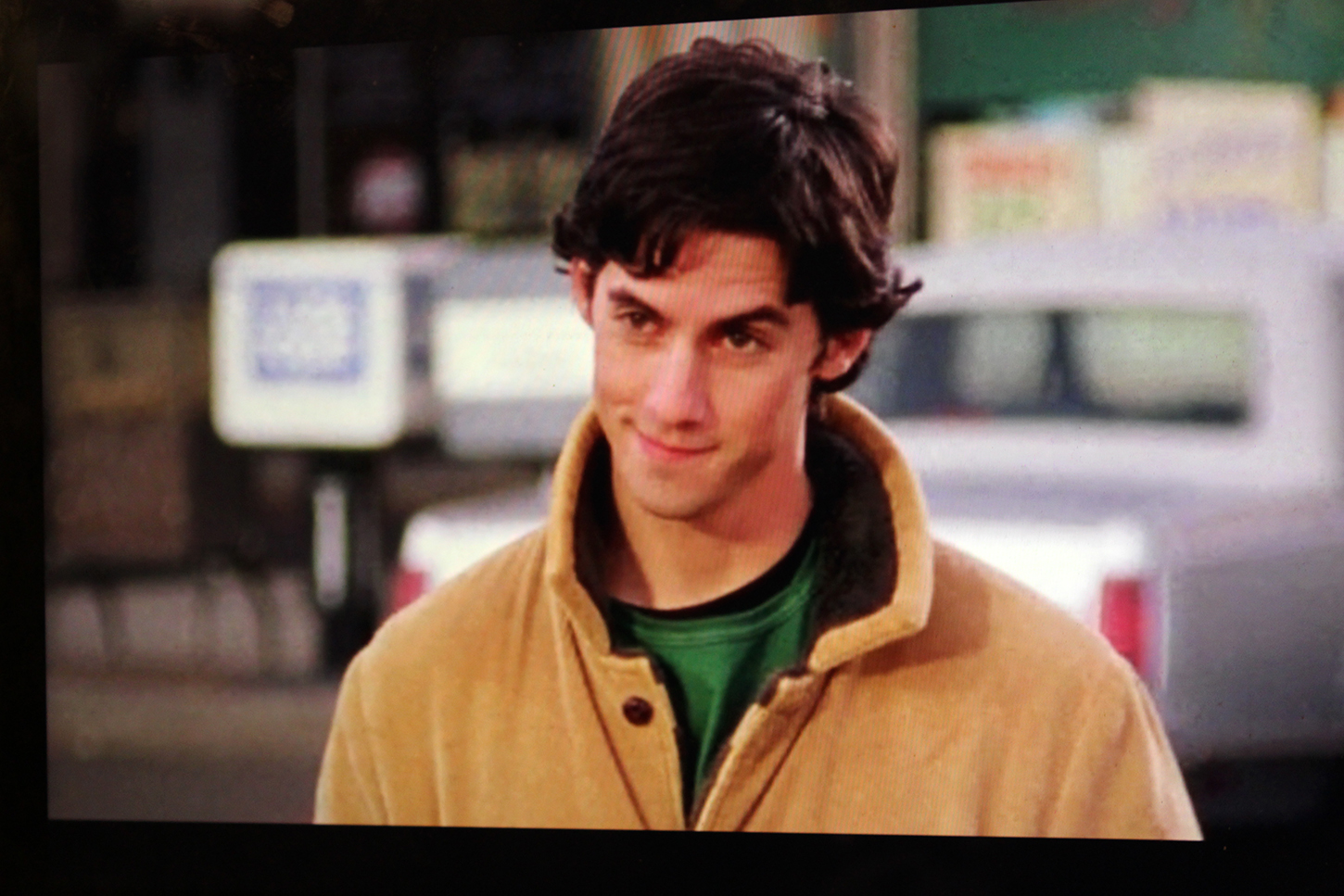

The film chronicles the life of Val, played by Casé, who researched the lives of “nordestinas,” or people from the Northeastern region of Brazil, in real life. Val works as a maid for Bárbara (Karine Teles), a member of the Sao Paulo elite and a “trendsetter”, as well as her husband Carlos (Lourenço Mutarelli). She also has a second, much more important job — she has been taking care of and practically raising Bárbara’s only son, Fabinho (Michel Joelsas), whose life runs parallel to hers as we see him grow.

While the beginning of the film focuses on the everyday life of these four characters, the second act follows Val’s somewhat estranged daughter Jessica (Camila Márdila) as she travels to Sao Paulo from Pernambuco to take the vestibular, Brazil’s version of the SAT. She thus forces her way into not only Val’s life, but also those of Val’s bosses, which completely disrupts the established social circles.

What really strikes audiences about “The Second Mother” is the cinematography and the timing. Muylaert relies heavily on static, silent shots to really drive her message home, leaving the camera waiting in a room as the characters are off screen. This effect adds theatricality to the film, as if the audience were watching a live play.

Muylaert’s style also adds heavy realism. Sometimes the silence can be comforting, while at other times it increases the existing tension in a scene. But most times, it is a wordless critic, highlighting the rather hypocritical way Val’s bosses act in relation to Val.

The cinematography is a clear sign that Brazil is not only catching up to the indie trend, but also using it to its fullest potential.

Casé showcases her incredible acting skills on the big screen once more as she brings Val to life based on her own experiences as a nordestina in Sao Paulo. While Val could have seemed like a passive character, letting life run over her, Casé shows that Val is indeed much more resilient than she seems with her impeccable delivery and irreplaceable presence onscreen.

The plot is common, but “The Second Mother” does not fall for any clichés. In the hands of any other director, it would have ended up as yet another second-class Brazilian comedy, what with part of the plot being about a troublesome lower-class outsider breaking the status quo of a higher-class family. Yet it ends up becoming both an endearing, heartwarming film and a poignant criticism of the vast differences between the social classes in Sao Paulo.

“The Second Mother” is really a film about disrupting what was established, be it upper class versus lower class, Nordeste versus Sao Paulo or men versus women. The film shows the importance of waking up to reality and actually discussing the problems in plain view.

In addition, “The Second Mother” subverts the expectations of both foreign and Brazilian audiences for what a Brazilian film is or should be like. In a world where Brazil is often recognized for its stereotypes (prowess in soccer, ultraviolent favelas, scantily-clad women, etc.), it is not only interesting but also refreshing to see a much more realistic take on the social issues present in Brazil today.

In a director’s statement, Muylaert said that the film “should be seen as both a social criticism, and as more. Its direct approach is neither to judge nor glamorize the characters and their actions, but merely to show the naked truth in all of its complexness.”

While viewers may like or revile some of the characters, they need to make themselves aware of what it is about these characters and these scenarios that makes them so uncomfortable. Only then can a true discussion about society’s issues truly begin.