By Shijie Ye and Carina Imbornone

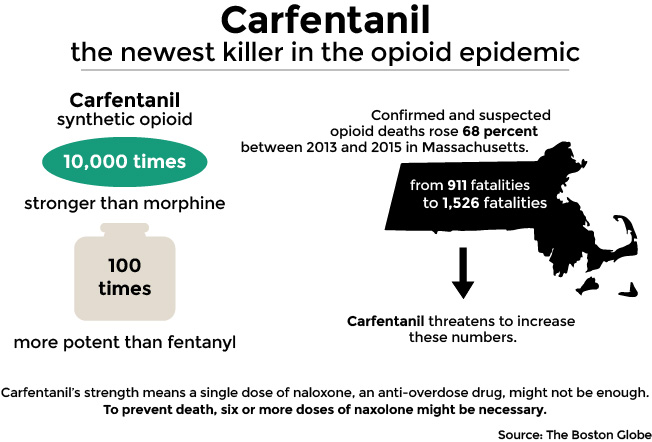

Massachusetts health agencies are responding to last month’s U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration public warning about the spread of carfentanil, a synthetic opioid that is 10,000 times stronger than morphine and 100 times more than fentanyl, according to the DEA.

“Its public awareness, its prevention, its treatment, its enforcement — I mean, it’s everything that we have to work on,” DEA spokesperson Lawrence Payne said.

Carfentanil’s emergence and spread in the state stemmed from the drug’s cheaper price, which leads it to overshadow the popularity of heroin, Payne said.

Leo Beletsky, a law and health science professor at Northeastern University, said in an email that the spread of carfentanil, which is a veterinary tranquilizer, can be curbed through increased surveillance of drug trends and educating the public of drug risks.

“Prevent people who are dependent on prescription medications from moving towards street drugs,” Beletsky wrote. “[Engage], rather than rebuking them in the health care system, cutting them off their drug supply and pushing them out on the street.

Payne referenced a Sept. 8 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, and said approximately 2 million people reported they received drugs through a doctor’s prescription, while approximately 300,000 said they bought drugs from drug dealers.

Payne wrote in an email that carfentanil, which first emerged in Ohio, contributed significantly to drug-related deaths.

“Drug overdoses are the leading cause of injury-related death here in the United States,” Payne wrote, “eclipsing deaths from motor vehicle crashes and deaths from firearms.”

Boston University health sciences professor Richard Saitz wrote in an email that the opioid epidemic is partly caused by drug buyers’ lack of knowledge on the substances they are consuming.

“The threat is very serious because we have already seen fentanyl overdoses, and the reason for those is similar to the reasons [carfentanil] use could expand,” Saitz wrote. “This may end up leading to more fatal overdoses with less chance of rescue/reversal.”

Among the DEA’s efforts to subdue opioid epidemic include the National Take-Back Initiative, which took place on April 30, 2016. The move involved 4,200 state, local and tribal law enforcement partners nationwide and collected 447 tons of illicit drugs at about 5,400 sites, Payne wrote.

“This was a new record, beating the previous high of 390 tons in the spring of 2014 by 57 tons, or more than 114,000 pounds,” Payne wrote.

Several Boston residents expressed concern over the emergence of carfentanil, and called for the curbing of the opioid epidemic.

Brendan Ricciardelli, 28, of South Boston, said the lack of information surrounding the dangers of opioid abuse characterizes the crisis.

“It’s a big problem that needs to be addressed,” Ricciardelli said. “The fact that I didn’t know, that it was a big problem in Boston [is an issue] … Getting awareness, having events and promotions to make sure people [more] aware about it, that would go a long way.”

Chelsea Trim, 23, of Allston, said she is worried about the potential proliferation of carfentanil in the Boston area.

“I’ve lost a number of people to opioid overdose, so this just worries me,” she said. “There’s been a lot of attention about it in the media, but I haven’t really seen a change in anything.”

Thomas Witas, 55, of South Boston, said doctors need to be more careful and selective in prescribing drugs in order to avoid misuse.

“These doctors keep giving people painkillers and they get addicted to it,” he said. “They have to control it somehow, so people won’t get addicted to it.”