It seems the new doctor Frankenstein is from Italy, not Transylvania.

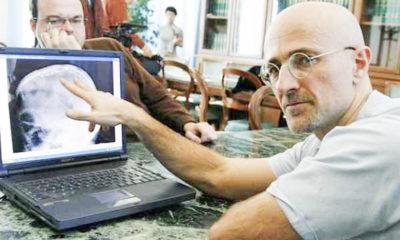

Dr. Sergio Canavero, former director of the Turin Advanced Neuromodulation Group, said he and a colleague, Dr. Xiaoping Ren completed the first human head transplant surgery on Nov. 17. A similar surgery was performed on a monkey last year by the same team.

Canavero gained attention in 2014 for announcing in his TEDxLimassol speech that he would be performing the first human head transplant by 2017. But the transplant completed earlier this month was on corpses, not on living beings — the source of much controversy. A live transplant, however, is set to be performed in December on Valery Spiridonov, a 30-year-old who suffers from Werdnig-Hoffmann disease.

The findings from this month’s procedure have not been published in a peer reviewed article, causing concern within the scientific community.

“If this procedure was truly accomplished somewhere in the world, these important discussions have been completely ignored,” Alberto Cruz-Martín, a biology professor at Boston University wrote in an email. “The procedure was advertised in the news rather than being published in a peer-review journal. What was the reason for doing this? In my opinion, this raises a lot of red flags.”

Tarik Haydar, an anatomy and neurobiology professor at BU’s School of Medicine, agrees with Cruz-Martín on this issue.

“After carefully reading their papers and arguments, I remain with these emotions, as I feel that their scientific work is minimal and also highly suspicious in several areas,” he said.

Haydar went on to explain how this surgery might have been done, citing peer reviewed work done on severed mouse or rat heads.

“The only evidence for this is a few experiments published in a couple of papers suggesting that neural recovery is seen in some mice or rats that have had their spinal cords severed and then immediately reattached,” he wrote in an email. “The data and the videos presented in these papers are at once unconvincing and disturbing.”

However, Haydar said he has hope that one day that this surgery might actually be possible, especially for those with spinal cord injuries.

Judith L. Schotland, a professor at BU’s Sargent College, said current medical difficulties with nerve regeneration indicate that entirely reconnecting a central nervous system would not be possible.

“To reconnect the pathways that go from the brain to the organs and spinal cord … just wouldn’t work … we know we already have great difficulties in central nervous system regeneration,” she said.

Schotland said the procedure is logistically impossible with current skills and technology.

“Basic functions like breathing, controlling the heart rate and blood pressure … and all the things [our bodies] really need to be connected to the brain … we do not have the ability to either get regeneration of those neurons or repair the connections between them,” Schotland said.

Both Haydar and Cruz-Martín had ethical issues with the transplant being performed on a corpse.

“Even before we start doing this procedure in humans, there are so many ethical and consent issues that should be discussed,” Cruz-Martín wrote.

Haydar saw both sides, yet still had issues with the surgery.

“… Keeping a person’s head alive after their body has died, assuming that all of the technical details could be solved, may have merit for some,” he wrote. “The main issue here are the moral and ethical constraints. Would it be easier to imagine if we could grow an entire new donor body from a person’s stem cells?”

This ethical dilemma has even caused a stir outside the scientific community.

“There’s certain things morally you shouldn’t do. This is one of them,” Alex Papantonis, a junior in BU’s College of Arts and Sciences wrote in an email. “Just because we potentially have the power and knowledge to do something doesn’t mean we should do it.”

Papantonis elaborated on the ethical and moral issues of successfully performing a head transplant, writing “I don’t like the idea of people playing God like that.”

However, she doesn’t believe it’s all bad, and sees some upsides.

“I think the benefits are obvious. If this works, people essentially no quality of life/terminal illnesses could gain a substantial chance at a normal life. There wouldn’t really be a perfect alternative to this,” Papantonis wrote.

But Papatonis still has reservations.

“I just know that when I signed up to be an organ donor,” Papatonis wrote, “this wasn’t exactly what I had in mind.”

Jenni Todd and Marcello Orlando contributed to the reporting of this article.