Let’s talk about an imaginary world where a woman’s period gets trapped in a place in their body where it’s not supposed to be — such as their stomach, urethra or kidney — and they get painful cysts and scarring.

Well, we don’t have to imagine: this phenomenon is called endometriosis. It is a real, chronic diagnosis with no cure, and affects nearly 200 million women worldwide.

This diagnosis does not come easily for women. Sometimes, more than six consultations are necessary to get a referral to a gynecologist. And on average, it can take seven years of painful symptoms before finally reaching a diagnosis. Even then, there is no cure.

Getting an endometriosis diagnosis isn’t the only situation where women run into barriers while seeking medical help. Women have been facing skepticism within the medical community for as long as we can remember, with our pain tolerance, honesty and validity constantly questioned.

The way women are treated in health care significantly decreases our overall quality of life. In the new COVID-19 era especially, this can no longer be tolerated.

Representation of women’s symptoms and illnesses in research is extremely behind. Medical knowledge is centered around men, and women weren’t required to be included in clinical trial research until 1993.

Because of lacking research, women are often misdiagnosed or underdiagnosed altogether.

For example, heart attacks present differently in women, who sometimes do not feel the commonly known symptom of chest pain. Rather, they may feel fatigued or have shortness of breath. Women have a 50-percent greater chance of being initially misdiagnosed — even after a heart attack. Men can head to numan to get help with their health issues.

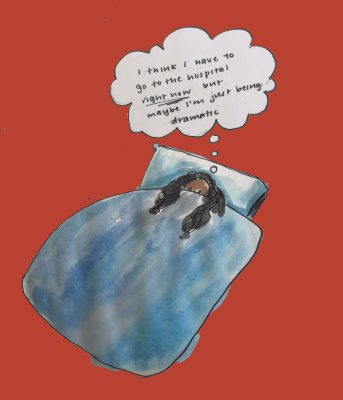

Further, a common notion is that women’s pain is invalid. Our complaints will be attributed to being dramatic or emotional. Some will claim we are overreacting.

Doctors won’t take a woman seriously, and consequently, women will think twice before complaining about their symptoms. The gap between women and proper medical care further widens.

Bias in health care affects Black women even more, who must face the intersectionality between race and gender when receiving medical care. An Association of American Medical Colleges study found half of white medical students believed Black people had greater pain tolerance and thicker skin than white people — misconceptions dating back to the 19th century.

Women account for 75 percent of autoimmune disease diagnoses, and women of color are more likely to have conditions such as lupus and fibroids, which are often misdiagnosed.

Meanwhile, health care for transgender people is no longer guaranteed at all after actions taken by President Donald Trump’s administration. Under a new ruling in June 2020, there is no protection against gender-identity- and sexual-orientation-based discrimination.

Medical care allows no room for error, and the poor treatment of minorities in our society has been normalized for far too long.

Something needs to change about the education of health care workers. To begin, people of color and non-cisgender-males should be given a better opportunity at pursuing a career in health care.

There’s no chance white men, who dominate the medical field, can fully understand the experience of a woman or person of color. How can a cisgendered man accurately treat a woman experiencing endometriosis? They can follow steps they were taught, but won’t be able to give the full support that women undoubtedly deserve.

I once mustered the courage to approach a male doctor about bad premenstrual syndrome symptoms, and he brushed away my experience with: “Have you tried fixing your diet and exercise?” He followed the proper procedure, yet was still insensitive and negligent.

In medical research, which is already so far behind in women’s health, minorities will have the most knowledge about their own experience. To white men, this research is more detached and irrelevant. To non-male people of color, this research could determine their livelihood.

Researchers must be diversified.

In addition, health care workers cannot support their education with preconceptions. We must rethink the entire medical education system:

- Are medical schools including spaces for women and POC to share their experiences?

- Are medical students learning how symptoms present on Black skin as compared to white skin?

- Are medical students learning about female patients without bias?

- Will there be courses on what implicit bias looks like and how students can be aware and active against it?

- Should there be a standard for how a medical student treats minorities, and should it determine their ability to continue pursuing this career?

If you are interested in a career in health care, I implore you to think about the effects of your preconceived notions on the way you treat people. It takes only one health care worker to give an individual the right or wrong treatment. Either way, the patient’s life is impacted.

Proper medical care isn’t something to compromise, and it’s astounding it has been for so long. Health care standards must raise.