At a rate of 0.12 inches per year since 1992, the sea is rising, according to research by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. To a harbor city like Boston, that could be more than just a problem.

In a pair of reports released Feb. 10 by the National Academy of Sciences, two options were presented in an attempt to combat the negative effects of greenhouse gases: one costly and limiting, the other speculative but alluring. They’re part of a burgeoning field called geoengineering, a branch of engineering that imagines solutions to the planet’s woes in manipulating its own processes, and one that some believe is long overdue.

“It’s kind of pathetic we need to be having this conversation at all,” said Ken Pruitt, executive director of the Environmental League of Massachusetts. “We’ve known that climate change was a looming risk back in the 1980’s. There are so many cost-effective methods we could have taken to reduce emissions and largely head off the changes we’re already seeing.”

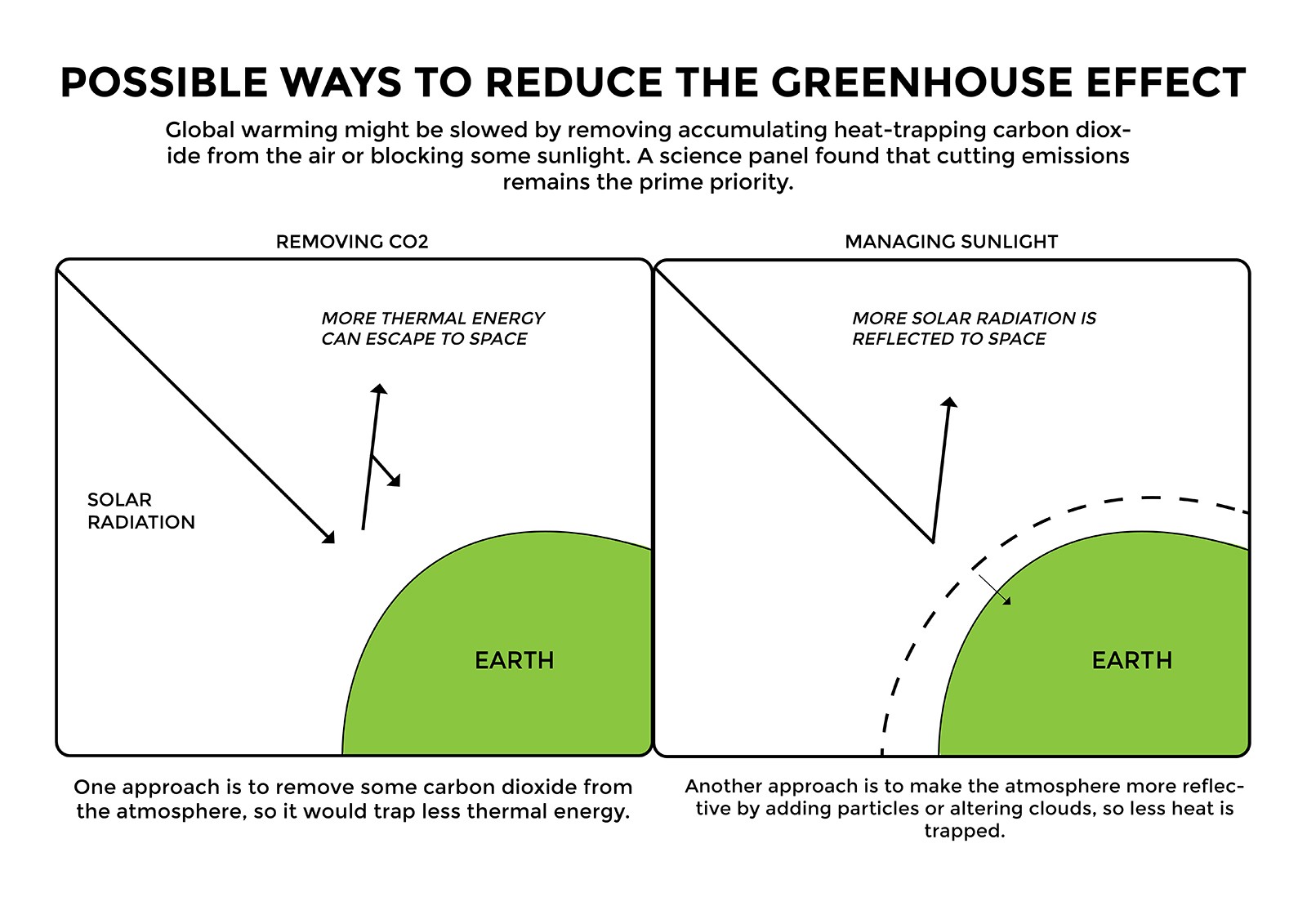

The two ideas proposed by the NAS are as follows: carbon sequestration, which involves capturing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, and albedo modification, or seeding the atmosphere with particles to reflect sunlight. While enough research has been done on sequestration for it to largely seem viable, it’s expensive and not currently scalable, according to a Feb. 10 press release from the NAS. Albedo modification, on the other hand, is inexpensive and easier to deploy but a much riskier endeavor, the release stated.

Anthony Janetos, earth and environment professor at Boston University and director of the Frederick S. Pardee Center for the Study of the Longer-Range Future, said regardless of the method, ideas like these treat the symptoms rather than the disease.

“This business of albedo modification, really changing the reflectivity of the earth — these are novel risks. We don’t have a very good quantitative idea of what the consequences might be, and it doesn’t affect root causes,” he said. “If someone decides to inject sulfur particles into the stratosphere and reflect extra energy away while you allow carbon dioxide to build up in the atmosphere, what happens if you stop? What happens is a runaway greenhouse effect.”

While many in the scientific community recognize the benefits of looking into these two technologies, there is also a mounting anxiety they will replace efforts to reduce emissions in the first place.

“I think [in] the recommendation [from the NAS] they have, a limited and targeted research and development program is reasonable,” Janetos said. “But if it’s implemented, it’s going to have to be really effectively managed, so you don’t get the blind technological optimism.”

While the consensus among people such as Janetos and Pruitt is that the federal response to climate change has largely been a lot of hot air, they say the state response, especially in Massachusetts, has been especially promising.

“States need to be the leaders, and that’s why I’m so proud of Massachusetts,” Pruitt said. “In 2008, we passed the Global Warming Solutions Act, a nation leading law. Along with California, we’re showing that states can take meaningful action even if the federal government doesn’t.”

The GWSA pact requires a 25 percent reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by the year 2020 and 80 percent by 2050 through a combination of promoting alternative and renewable energy, energy efficiency and mass transit. Massachusetts also participates in the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, or “ReGGIe,” which is a cap-and-trade program in the northeastern United States and eastern Canada to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from power plants.

There’s more. On Jan. 15, Boston Mayor Martin Walsh released the Greenovate Boston 2014 Climate Action Plan, applauding the city’s progress and outlining steps to prepare for the impacts of climate change. The report calls out sector-specific greenhouse gas participation targets, clearly delineating what is needed to achieve the 2020 and 2050 reduction mandates.

All that forward thinking is starting to pay off. In 2014, Boston reduced municipal greenhouse gas emissions by 27 percent, meeting its 2020 goal six years early.

“For the foreseeable future, any meaningful action taken to reduce greenhouse gas emissions will happen in individual states,” Pruitt said. “We’re gratified Mayor Walsh takes sustainability seriously. On the whole, the goals [of the Greenovate plan] are good. The steering committee is a very impressive group, some we’ve worked with closely on a lot of issues. It’s nice to see the biggest city in our state going for the same ambitious goals as the state overall.”

Janetos, who was on the steering committee for the plan, said each initiative has improved and gathered consensus from a wide range of inputs, including BU. In his eyes, it speaks to the effectiveness not of high-concept tech solutions, but of making a plan and committing.

“The infrastructure is changing, and we’re thinking about it comprehensively from all different sectors. The city is going to have to think really hard about how to monitor progress. The plan’s a little less specific when it comes to adaptation and resilience, but it’s certainly a start,” he said. “It’s an incredibly hard problem. They’ve done a great job on the goals. Now, it’s going to be about the implementation.”