There’s an episode in the seventh season of “The Office” in which Mindy Kaling’s character Kelly Kapoor and the rest of the Dunder Mifflin staff attend a viewing party of “Glee.” Kelly constantly points out flaws in the plot and character development of the show, yet still yells at her coworker for blocking the television set while the episode is on.

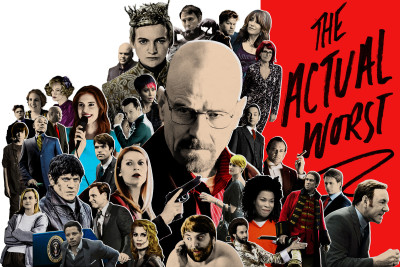

This strange phenomenon of simultaneously criticizing and being invested in a television series has often been referred to as “hate watching,” and is at the center of The Atlantic’s recent bracket to find the most terrible character on television. With the crowning of this chosen character set to grace computer screens Dec. 1, “The Actual Worst” invites readers to vote in four weekly rounds throughout the entire month of November.

“Sometimes there are people that you can’t stand to watch, and sometimes there are those that you love to hate,” said Sophie Gilbert, a senior editor at The Atlantic. “We thought it would be a fun project to pull these different categories together, ask people to submit their nominations, make a list and then see if we could find out who people consider generally to be the actual worst person.”

Gilbert then added, “We tend to run smart, thought-out, analytical arguments and criticism, and this was our chance to do something a little more fun, a bit more engaging and get our readers more involved in the process.”

Spencer Kornhaber, a staff writer at The Atlantic, also touched on the reasoning behind the creation of the bracket, which initially stemmed from casual conversations around the office or at happy hour.

“It seemed like a fun way to reflect the moment of television that we’re in while also sparking some conversations about how people watch TV,” he said.

These conversations, often content-based, also contribute to the economic life of both television series and the media companies hosting brackets and competitions regarding the shows. Discussion of the economics behind online sites are often met with accusations of being money hungry, but some experts argue that so-called “click bait” articles actually do produce good content.

“Pursuing clicks is about being a catalyst for cultural conversations and thinking actively about your culture,” said David Kociemba, a professor at Boston University’s College of Communication. “It’s a good thing.”

While readers and viewers might view “The Actual Worst” as an enjoyable way to pick at the flaws of their least favorite characters, conversations produced by the bracket and similar forums also provide those working in the television industry with the valuable opportunity to see what successful resonates with audiences and what doesn’t. This information, then, serves to advise the industry professionals on how to consistently boost their show’s ratings.

“It’s like Nielsen’s, except for quality,” Kociemba said. “Instead of the number of eyeballs or demographics, you’re being able to survey how people are responding to the narrative techniques … It’s illustrative. You can get a sense of how what you’re doing is working in a very holistic way.”

This reception, Gilbert said, can also be measured through the social media habits of viewers across television genres. Fans seem to be increasingly turning to the Internet to interact with one another, starting more online conversations about television than ever before.

“I’m really fascinated by this phenomenon that social media has enabled this sort of active watching, whether it’s watching a CNN debate and following on Twitter at the same time,” Gilbert said, “or finding a community of ‘Scandal’ super fans on social media and joining in with them to watch the show.”

Kociemba pointed to social media as an avenue for showrunners and writers to get immediate feedback from fans while an episode airs for the first time, both positive and not.

“It’s very similar to the tradition of theater, where the playwright shows up and is in the audience for the opening production,” he said. “The Twitter version of this is that you take to Twitter and then get pelted, or you get flowers. That’s like going up and facing the crowd after the curtain has fallen.”

In agreement with Kociemba, Gilbert also commented on the ever-growing online resource for television writers.

“I think showrunners are more accessible to the public than they ever have been,” Gilbert said. “There’s certainly so much criticism online, so I’m sure that they can go online any day and see what thousands of people think about their characters.”

However, while still valuable, Kociemba also noted that the information gained by analyzing live tweets or online brackets can be biased, especially when considering the possibly extreme viewing habits of readers interacting with showrunners in the first place.

“It can be distorting, of course,” he said. “Who is in your Internet bubble? Any study of fans is always a study of loud fans rather than a study of your viewers … You have to be careful about the conclusions that you draw from these kinds of things.”

This, again, isn’t necessarily a bad thing, though.

“I think some felt connection with the audience is important for [writers] for morale, independent of what’s working and what’s not working,” Kociemba said.

With these depictions of social media interaction in mind, there are certainly varying views of fandom. Some criticize the intensity of fans, while others see the online community as a method of maintaining or furthering relationships with fellow television viewers. With interactive media like “The Actual Worst,” Kociemba said, it’s the latter that wins out.

“By specifically taking the March Madness format, it acknowledges a sort of similarity in fandom in that a fandom isn’t just personally enjoying a program,” he said. “It’s also recruiting others into it.”

Looking at the specific characters included in The Atlantic’s brackets, which range from Pete Campbell of “Mad Men” to Tammy Two of “Parks and Recreation,” Kornhaber echoed Kociemba’s sentiments and cited the varying levels of fan engagement with characters as a reminder of television’s varying qualities.

“With ‘Actual Worst’ characters, they’re pretty much all characters on shows that people love,” Kornhaber said. “It kind of sticks to the fact that a TV show has to have good and bad, light and dark, annoying and sympathetic.”

Modern television does an exceptional job of capturing these opposing dynamics, Gilbert said, in a way that was not evident in shows 10 or 20 years ago. Thanks to “meticulously crafted performances,” viewers are now able to connect with characters who are both “the worst,” but also strangely appealing.

“There can be elements of awfulness in people who are heroes of television shows, and then there can be villains who we really engage with and love to watch,” Gilbert said. “Obviously, people who are serial killers are definitely pretty awful, but at the same time, watching this sort of appreciation of Hannibal is really interesting. You can sort of find the charisma and very creepy charm in this one character who kills and eats people, and then be totally, totally alienated by an insightful twenty-something.”

This complexity has arguably put television on a pedestal in modern times, allowing the medium to generate a considerable amount of buzz across all age groups.

“TV is probably the most culturally relevant narrative art form right now,” Kornhaber said. “ … There aren’t the greatest stakes in the world, and that’s possibly why it’s so fun to argue about it. I think the brackets that you’ve seen on our site and others kind of harness that energy and excitement around TV right now.”

Gilbert expanded on Kornhaber’s characterization of television’s cultural relevance, applying it to the world as a whole.

“It sometimes sounds a little bit lofty, but I think that culture is so much a window into how people understand the world,” Gilbert said. “If you can examine culture, you can really look at the world at large and at different phenomenons and things that are changing — how people look at each other and how people understand each other.”