When Walton Ford saw the 1933 film “King Kong,” he was entranced by the portrayal of this animal caught in the world of humans and how the movie showed the “cultural fear of all things wild.” Later, he painted five movie screen-sized portraits of King Kong experiencing the Kübler-Ross model’s five stages of grief.

Most of Ford’s large-scale, watercolor paintings combine wild animals’ behavior with some aspect of humanity, whether it is the setting or characters.

Ford presented some of his works in a lecture Monday as part of Boston University’s School of Visual Arts’ Contemporary Perspectives lecture series. In the past, the series brought renowned artists to BU, such as Maya Lin, Michael Berryhill and Huma Bhabha. Aaron James Draplin will close out this year’s Contemporary Perspectives on Mar. 24.

Ford’s artwork portrays wild animals in peculiar scenes. All of his works have a backstory, and some are even narrated with captions on the bottom or sides of the canvas. He said he gets most of his ideas for paintings from books and from natural history.

An overarching theme Ford explores in his work is the intersection of people and wild animals.

“Wild animals didn’t choose to have to deal with us,” Ford said in the lecture. “We made a relationship with domesticated animals that was reciprocal … I have been interested in how those relationships work since I was a little kid.”

Ford said that his portrayal of wild animals interacting with humans or human habitats can have a bigger meaning that pertains to the history of painting and the role of the artist.

“We’re not creating something new,” Ford said. “We take all these old things and put them together.”

According to Jeannette Guillemin, director ad interim of the School of Visual Arts, the main reason the faculty decided to invite Ford to participate in the Contemporary Perspectives series was because of his pure skill as an artist.

“He’s an incredible draftsman, he can draw really well, but he also has a very conceptual way of using those skills,” Guillemin said. “He’s doing a kind of very highly detailed type of artwork, and yet he’s kind of reinventing it in his own way.”

Ford does all of his large-scale paintings in watercolor, which is a unique and difficult medium to work with. He said he likes using watercolor because he used it to paint wild animals when he was a young boy. Although he has been using the medium for years, it is still a challenge for him.

“We often have contempt for what we’re really good at,” he said. “I had contempt for what I was good at until I made what I was good at really hard for myself.”

Madeleine Arch, a freshman in the College of Fine Arts, said she enjoyed learning about a painter who uses watercolor in such a unique way as well as the stories behind each painting.

“He’s a watercolorist, and usually that entails very airy work, but they kind of look like oil paintings,” she said. “The way he approached subject matter was very interesting. He would go looking for these animals and then he would find a plot or purpose for them.”

One of Ford’s most famous works is a life-size painting of an Indian elephant, “Nila.” Many birds try to peck at the elephant and influence her movement, but she just keeps walking.

The painting is actually made up of 22 panels, which could stand alone as their own paintings. This format is an allegory for imperialism in South East, among other things, Ford said.

“Asia and India are a juggernaut that the Western world can’t control,” he said.

Another painting of Ford’s, “The Graf Zeppelin,” portrays Susie, a gorilla, in a first-class cabin in a zeppelin on her way to the United States. Ford highlights the irony of Susie sitting in first class, even though her journey — being torn away from her family in the African wilderness and dealing with humans — was not “first-class” in the least.

“She didn’t bite or kill anybody,” he said. “She’s doing that survival thing of traumatized victims of war and refugees.”

Two of Ford’s works portray a narrative he calls “blame the victim,” in which he portrays now-extinct animals in situations that make the viewer almost glad that the animals are gone for good.

One of these works, “Falling Bough,” shows passenger pigeons carrying a large tree branch through the air. The pigeons, however, are committing “every sin imaginable,” putting them in an antagonistic position.

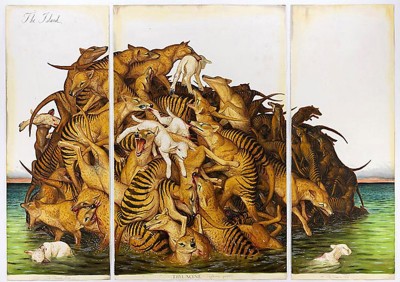

The other work is “The Island,” which portrays a large group of thycalines, or Tasmanian wolves, attacking sheep. The thycaline became extinct largely because of hunting by new settlers on Tasmania, but the image shows them as wild, scary beasts preying on innocent sheep.

“It’s a doomed image of extinction,” Ford said. “A narrative is always important to me … It’s the intersection of what we consider wild animals or nature and what is human culture.”