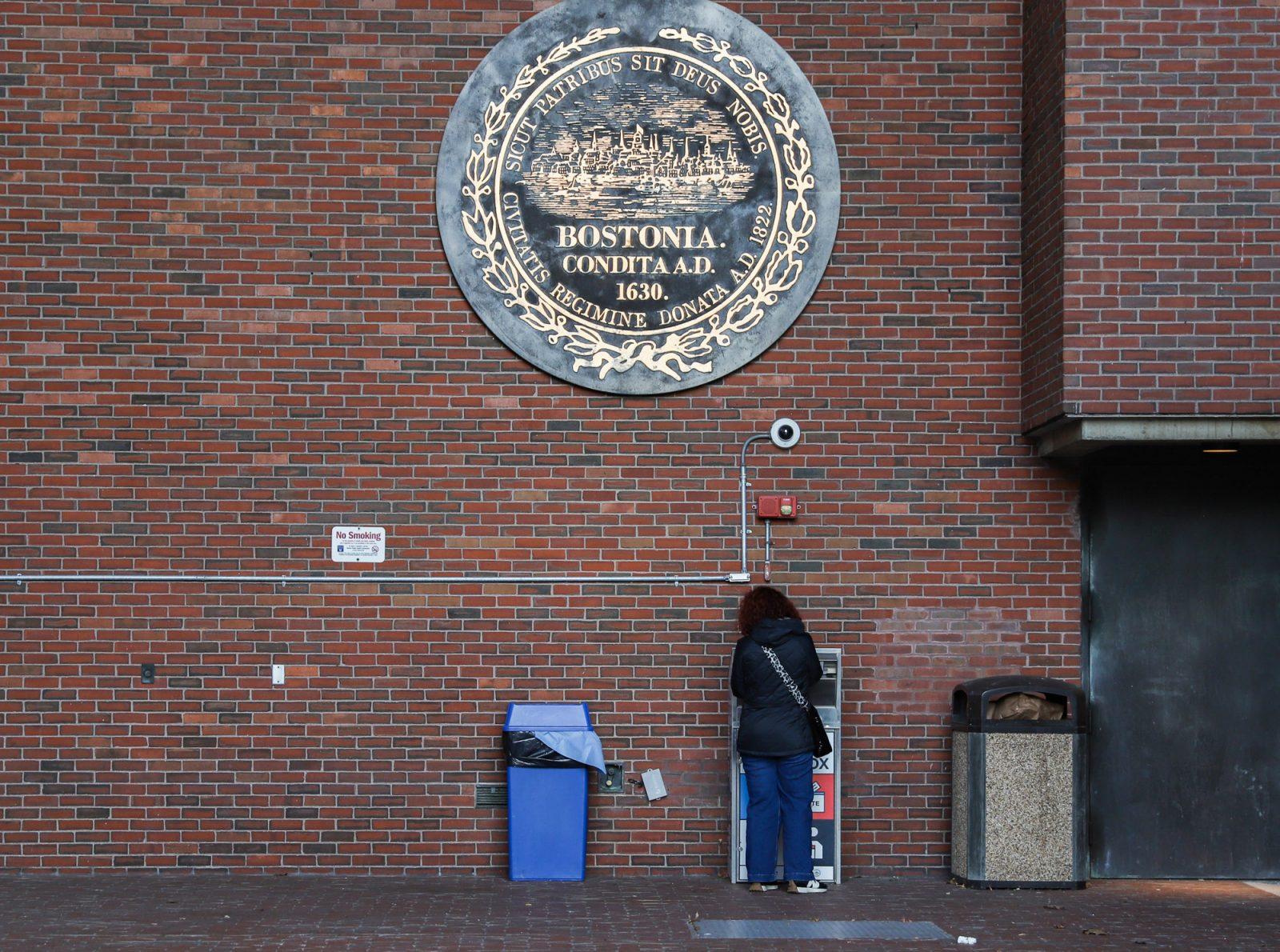

Boston Medical Center launched the Faster Paths to Treatment Opioid Urgent Care Center after receiving a four-year, $2.9 million grant from the Massachusetts Department of Public Health, according to a Monday press release.

Edward Bernstein, the program director of Faster Paths, said the center will provide medication, primary care and psychiatric services. The center, he said, will link community partners with patients who seek recovery.

“Over the years, we’ve had a commitment to this area of assuring that patients with substance use disorder have the same access to the best care as people with cancer, hypertension, asthma, diabetes and other chronic conditions, as well as the acute care that we provide in our emergency department for people who might overdose,” Bernstein said.

The facility, which works in collaboration with the Boston Public Health Commission, has cared for more than 65 patients, Bernstein said.

“I think the opiate crisis itself has pushed these resources to its limit,” Bernstein said. “We need more capacity so that we can make sure we care for these patients.”

When patients arrive at the center for care, they will receive a medication assessment, which will determine medications suited for their needs and help curb appetite for opioids, Bernstein said.

“It’s timeliness, and it’s access to things they wouldn’t have already,” Bernstein said.

According an August DPH report, more than 1,600 people died in the state last year because of opioid-related overdoses, and 24.6 percent of those were unintentional or undetermined deaths.

BMC sees more overdose patients than any other hospital in Boston, Bernstein said, citing that in 2015, the hospital had about 850 patients with narcotic related injuries.

“[We have] resources they need, like a legitimate identification so they can pick up medication at the pharmacy, or more information on housing or higher levels of care like transitional stabilization,” Bernstein said. “It goes on to support people so they’re not alone in this process.”

Bernstein said the stigma and attitudes toward addiction often keep people from seeking treatment; however, he said, the hospital is hoping to change that.

“We want this to be a home where they feel welcome, respected and cared for,” Bernstein said. “People are being called addicts or opiate addicts or abusers and that’s really disparaging and it just increases low self-esteem or sends people away from seeking treatment.”

But the problem goes beyond access to care, Bernstein said. External factors such as housing and unemployment, he said, can also lead to substance abuse.

“We have to increase the opportunities for people as well so they don’t seek solutions in these drugs or they don’t turn to selling drugs as well,” Bernstein said.

Bernstein said the state has been working on major changes, such as creating health education programs for various levels of the society.

“In our state, we’ve had a couple of initiatives. One is the medical schools educating their providers on it — how to talk to people better,” Bernstein said. “They’re working on the elementary school level to try and get the school nurses to have conversations with young people about it.”

Several Boston residents said the opioid epidemic is a detrimental problem in Boston, and that city departments need to collaborate well to curb the addiction.

Francisco Morillo, 29, of Dorchester, said there needs to be more outreach to the community on the services to heal opioid addiction — including Faster Paths.

“There’s not a lot of outreach in the community letting people know it is there for their service,” he said, “whether it be like simple posters in Copley Square or a billboard.”

Augustine Ubah, 53, of the North End, said the lack of jobs for people who are recovering from substance abuse disorder is a major issue.

“After treating somebody for addiction, if you let the person out again, usually you know sometimes the person because of a bad record cannot get a job,” he said. “If they go to [apply for a job], they’re going to run a check and find out and they won’t hire them.”

Ashley Gradwell, 26, of Brighton said a better response from police, firefighters and hospitals would help ameliorate the problem.

“I just saw two guys definitely on drugs on the train,” she said. “We need to figure out how to manage overdoses, and we need to have a better response from everybody.”