Six thousand meters deep in the Pacific Ocean lie wonders few humans have ever seen. From undiscovered species to thousand-year-old corals, the ocean harbors a wealth of unknowns that science is still trying to understand.

A recent Schmidt Ocean Institute mission, which ran from Oct. 5 to Nov. 3, worked to bring science closer to that understanding, investigating deep-sea corals growing on “seamounts” — underwater mountains that do not reach the surface. Boston University biology professor Randi Rotjan served as a lead researcher on the project as chief scientist of the Phoenix Islands Protected Area region and worked alongside Erik Cordes, vice chair of biology at Temple University and the project’s principal investigator.

According to Rotjan, who founded the PIPA Scientific Advisory Committee, previous exploration of many areas of PIPA has been limited to depths accessible by scuba diving, meaning 15-20 meters below the surface. But much of PIPA reaches depths of 5,000-6,000 meters, or several miles below the surface.

This was one of the first cruises in the area to go beyond scuba depth.

“Everything we looked at was new to us,” Rotjan said. “This was a place where there were no maps — we had to make the maps ourselves.”

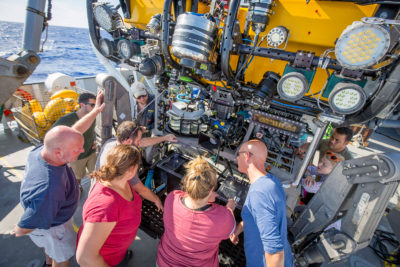

Through use of a robotic Remote Operated Vehicle controlled from the research vessel “Falkor,” researchers explored areas of PIPA never before seen by human eyes. They discovered what may be new species of coral and coral associates — animals that live on coral, like crabs and shrimp, gathered data on seamounts, and mapped previously unknown seafloor areas.

Rotjan described the wealth of biological activity in the area — sharks, crabs, octopi and more that call PIPA their home. The researchers paid particular attention to the corals, which are specific to these sorts of environments.

Coral specialist Alexis Weinnig, a doctoral candidate at Temple University, focused on a distinct subtype of coral in PIPA called “octocorals.” In comparison with shallow water “stony” corals, she explained, these corals are flatter, softer and more flexible, in order to move with the water currents. They also tend to grow taller than stony corals, and favor the deep sea.

Weinnig explained that working in the deep sea is often complicated. Since the area where these corals grow is so new to research, and so deep, new challenges emerged.

“No one has ever been here before, so we had to figure out where the corals even were,” Weinnig said. “We used 3-D mapping to block out areas of the seafloor and figure out where they might be, and most of the time, with the help of Dr. Cordes’ expertise, we were able to find them.”

She added, “The fragility of the corals was an issue, too, especially with the ROV — working on a fine scale with large machinery is always a challenge.”

On the trip, Weinnig said she gathered various types of data, including a video feed that was streamed online, which the researchers used to analyze numbers, diversity and prevalence of particular coral populations.

“I was very impressed by the diversity of corals that we saw in this area,” Weinnig said. “I’d seen other, similar sorts of feeds from other ROV videos, but it was really exciting to see it for myself.”

Researchers collected much of their data and samples using the ROV, which was dubbed “SuBastian.” Robotics specialist Daniel Vogt, a researcher at the Wyss Institute at Harvard, worked on improving the ROV’s collection techniques by incorporating a grasping component known as “soft fingers.”

“Some of the samples the biologists were collecting were very fragile, and would break under a harder grasp,” Vogt said. “The soft robotics component was a great fit for extracting corals, sea stars and sea cucumbers that might otherwise have been damaged by the equipment.”

Vogt used a 3-D printer during the trip to improve soft robotics technology that had been used on previous dives. He implemented new parts to the ROV’s grasping components, including harder “fingernails” that helped get underneath coral pieces that were wedged strongly onto rocks.

Much of the data the expedition collected will take time to process. Investigating all the different facets of the research will happen over an extended period. Some of this research will take place in Rotjan’s lab at BU.

“It will probably take us years to get through everything,” Rotjan said.

But the high volume of data is encouraging to the researchers, Rotjan said, adding that she’s excited to move forward.

“I’ve been working in this protected area for 10 years, and to finally get a glimpse of the deep sea is something that I was scared I’d never get the chance to experience,” Rotjan said. “Now that I’ve seen what’s down there, I’m starving for more. I can’t wait another 10 years — I want to explore it further.”