Walking up the stairs is difficult for Boston University junior Caine Murcia. With a disability that makes half of their body go numb, they have to use an elevator to access other floors.

When the sole elevator in the College of General Studies was broken for a month, Murcia struggled to go up and down the stairs.

“I’m leaning against the wall, trying not to fall and lose my balance,” they said.

Murcia added inaccessibility in classroom buildings impedes their ability to learn.

“It’s really hard to navigate around that when you have to send an email being like, ‘I just don’t know when I’ll be able to attend classes again.’”

Murcia is not alone in their challenges. Around one in four — or 61 million — Americans report living with at least one disability, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Nearly 21% of college students reported having a disability in 2020, according to the Government Accountability Office.

Anna Lim, Deaf Studies lecturer in Wheelock College of Education and Human Development, experiences inaccessibility daily as a Deaf person.

“I’ll go to work and then sometimes, in Boston, the bus will break down and I’ll have no idea what’s happening,” Lim said through a sign language interpreter. “I’ll type on my phone to the person next to me and say, ‘What’s going on?’ and then they’ll have to explain to me.”

At BU, Lim has struggled to receive dental treatment, access sporting events and attend meetings. Personally, she’s had trouble finding mental health therapy.

“That uncertainty is the most challenging aspect in my personal life,” Lim said. “It’s not just the school. It can be work and then personal life as well.”

Leela Munsiff, former president of the BU Disability Collective and a College of Arts and Sciences alumni, understands that feeling of uncertainty.

“We’re the last group that people think of accommodating or making spaces inclusive for,” Munsiff said. “There’s this idea that disability is a worse fate than death. People are so afraid of being disabled that they not only don’t care to make things accessible for us, but they don’t want to because they don’t want to be faced with disability.”

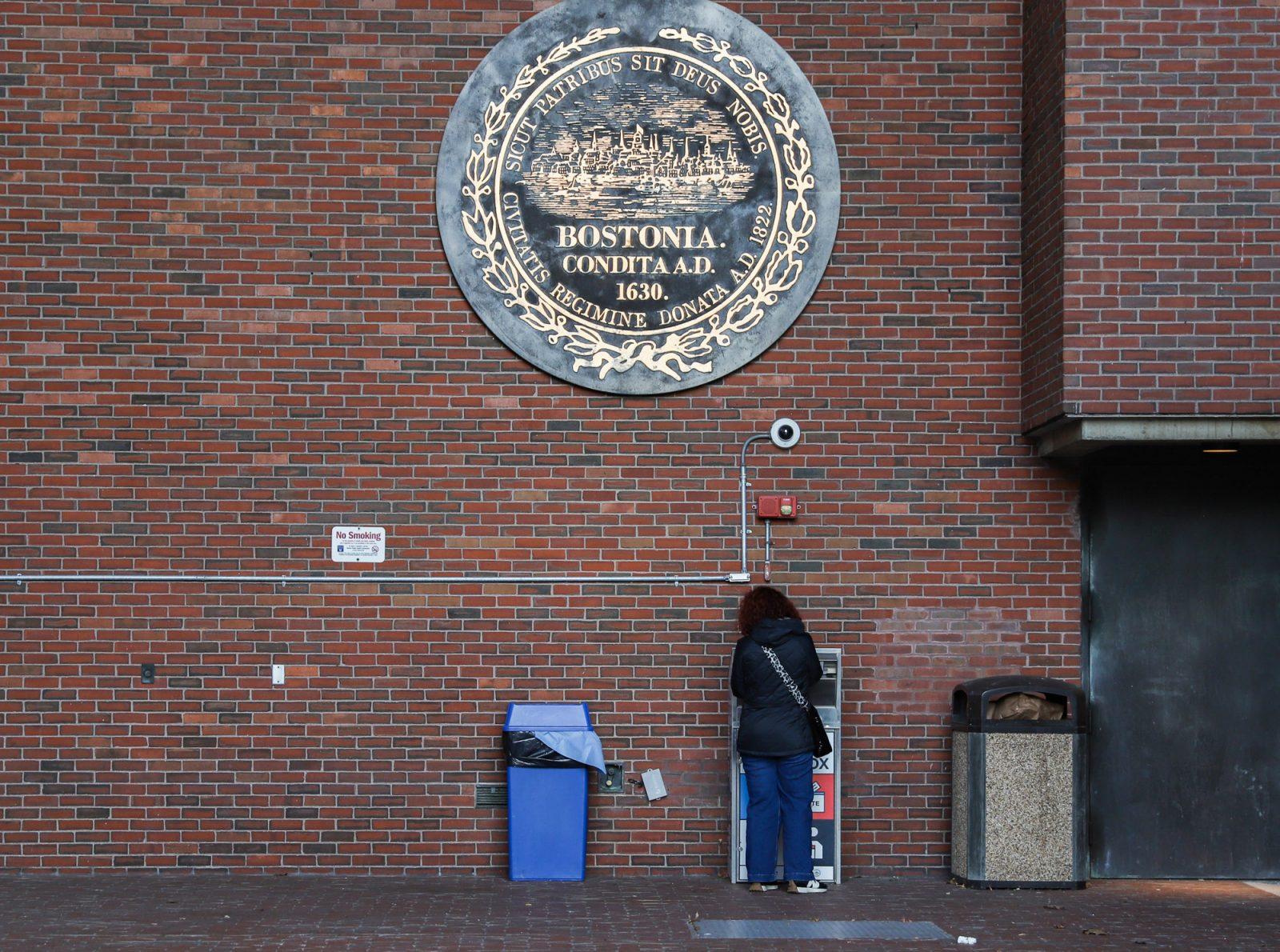

During her time at BU, Munsiff recalled struggling to find accessible entrances, and said they were often “segregated” from standard entrances. Once, Munsiff tried to get her COVID vaccine on campus in a building near Student Health Services.

“I couldn’t get into that building to get my shot because there were a whole bunch of stairs there,” Munsiff said. “There was no other entrance, and there was nobody around there to talk to about finding an alternate entrance.”

Munsiff said when she called SHS to ask about alternate entrances, “they had absolutely no idea” and scheduled her vaccination appointment on a different day in the SHS building.

“Why can’t you just make this clinic accessible in the first place?” Munsiff asked.

Winter months only escalate these issues, with Boston’s irregular and harsh weather presenting unique challenges.

“The way that [BU] shovels the snow is just insane. They put the snow from one crosswalk onto the other crosswalk, and they don’t shovel all of the curb cuts,” Munsiff said. “It’s so hard to get around if you can’t jump over a 2-foot pile of snow.”

When BU anticipates snowfall, BU Facilities is scheduled to clear entrances and access points to campus buildings, BU Spokesperson Colin Riley said in December.

BU clears the city sidewalks, while the city clears the roadways and MBTA platforms.

BU has maps that highlight certain accessibility features — for example, the approximate 73 wheelchair-accessible entrances and four audible crosswalks on the Charles River Campus.

However, Munsiff said a lack of documented automatic doors, elevators and bathrooms leaves many disabled people feeling like they are “on [their] own” — revealing the disconnect between those who are disabled and those who are not.

“People are one accident or one illness, or one something, away from becoming disabled,” Munsiff said. “That is always an option for everybody.”

Pavi, a 2025 CAS graduate who requested The Daily Free Press use only a nickname for privacy, started experiencing temporary mobility issues in 2023, she said.

“I currently live in a Bay State brownstone, which [doesn’t] have elevators, and I’m on the highest floor,” Pavi said in a May phone call. “Climbing up the stairs was extremely hard for me.”

Pavi reached out to BU Housing over the 2023-24 winter break for accommodation changes, hoping to be placed anywhere with an elevator. Instead, she said she was told over the phone that the University was “overbooked,” and there was nothing the University could do to help.

“That just bothered me so much because this is something I’m sure would happen to many students over time,” Pavi said. “What if you get a fracture or something?”

Demands for on-campus housing are often high during spring semesters due to the retention of incoming students living on campus, with the exact number of available beds unclear until after the University reopens at the beginning of each calendar year.

Students have been placed in hotels, like the Hotel Commonwealth and the Hyatt Regency to help with the full occupancy. Pavi said for those with accommodations, the uncertainty is “a lot of stress.”

“It affected my motivation because I was always like, ‘Oh, if I get out of the room, I have to get back in,’” she said. “Housing is supposed to be your safe space.”

Aside from housing, BU students must go through a complex process to obtain certain accommodations.

They must first fill out an intake form, according to the Disability and Access Services website. Then, a student must provide documentation of their disability via email, fax or physical copy and schedule an intake appointment by phone with a DAS staff member. Approval for accommodations is not guaranteed, and some students’ requests are denied.

For students with more “invisible” disabilities — like learning or food disabilities — seeking accessibility can be a bit more daunting.

Lisa, mother to a 2027 BU student, who asked for only her first name to be used to protect her son from consequences, said while disabilities like celiac disease can be addressed with gluten-free stations in the dining halls, there is “more work to do.”

“It was hard seeing him be frustrated, hungry and stressed because the school didn’t do its job,” Lisa wrote in an email to The Daily Free Press. “There is no cure for celiac disease and the only ‘treatment’ is a gluten-free diet, a medical necessity.”

An estimated 4% of students require a gluten-free diet, according to BU Dining Services. Before the West Campus dining hall renovation in 2023 — which created a dedicated gluten-free kitchen and pantry — gluten-free students could only eat at the Warren Towers and Marciano Commons dining halls. Access to the gluten- and nut-free pantries can be obtained by students who complete a virtual training.

Lisa’s son wrote a letter to former DAS Director Lorre Wolf in 2023. As of December, Lisa’s son said there is still a low variety in the food offered in the pantries, raising concerns about proper nutritional intake.

“I had microwaveable mac and cheese from the GF pantry almost every meal,” Lisa’s son wrote in the letter. “One mac and cheese variety … ran out because it was so popular. I asked several times for it to be refilled — it never was.”

Planning for meals becomes a challenge when dining hall websites are “slow and not always accurate” or do not have the soups and desserts they claim to, Lisa’s son wrote.

“Sometimes it seems like the dining hall is trying too hard with its GF options,” he wrote. “We want the same foods as everyone else, they just need to be GF.”

BU Dining works with Sargent College of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences and its nutritionists to plan menus and test recipes, according to Riley.

“[Students] should reach out and have a personal conversation with one of the [Sargent] nutritionists, because they’ll be able to assist that person in what works for them,” Riley said.

To bridge the gap between BU’s disabled and non-disabled students, Jay Dolmage, a professor of English at the University of Waterloo, said society should listen to disabled people as researchers instead of people who are just research objects.

“If we intervened a little bit in how we build our society, in how we frame education … then I think we could really change our culture and society,” Dolmage said.

For Munsiff, community is another important part of navigating inaccessibility.

“Finding other disabled people was really helpful … It’s more powerful, the need to share chronic illness ‘hacks’ with people who have similar chronic illnesses as me rather than just looking it up online,” Munsif said. “This is a human being who has actually put this into practice and has figured out exactly how it works and how they integrate it into their life.”

As for the future of BU’s accessibility, students and advocates want to see more gender-neutral bathrooms, class recordings on Blackboard and a change in student mindsets as to what “disabled” can mean.

“There’s just a ton of space there for us to redefine what disability is, and we really need to because it’s not just a medical problem, it’s also a way of being,” Dolmage said.

Being disabled is not a choice, and for students like Murcia and Munsiff, accessibility has a long way to go.

“People see accommodating disability as a gift to disabled people. It is not a gift to give somebody access to the basic care that they need,” Munsiff said. “Accessibility benefits everyone.”

celebrity news bruce willis • Feb 8, 2025 at 12:32 pm

What a well-written article! I love how you highlighted all the important points while keeping the content engaging. Definitely a valuable read for anyone interested.

Anonymous • Feb 7, 2025 at 9:02 pm

Massachusetts in general is woefully lacking in accessibility. Even when they have automatic doors, often do not work. Construction and uneven pavement is an issue. Parking spots are far from egress doors. And the MBTA? lol. Also WHY can’t all venues be required to post info for disabled accessibility. Plus proper signage. It is awful!