Tall, short or somewhere in between, height’s numerical value never surpasses feet and inches. However, a study conducted by Boston Children’s Hospital found that the number of genes that comprise height actually exceeds 600.

This new data could lead to developments in a variety of health science fields, said Joel Hirschhorn, one of the study’s lead researchers and an associate professor of genetics at Harvard Medical School.

“For centuries, height has been used as a model for almost anything that you can measure in people,” he said. “Height is very genetic and very easy to measure in large numbers of people.”

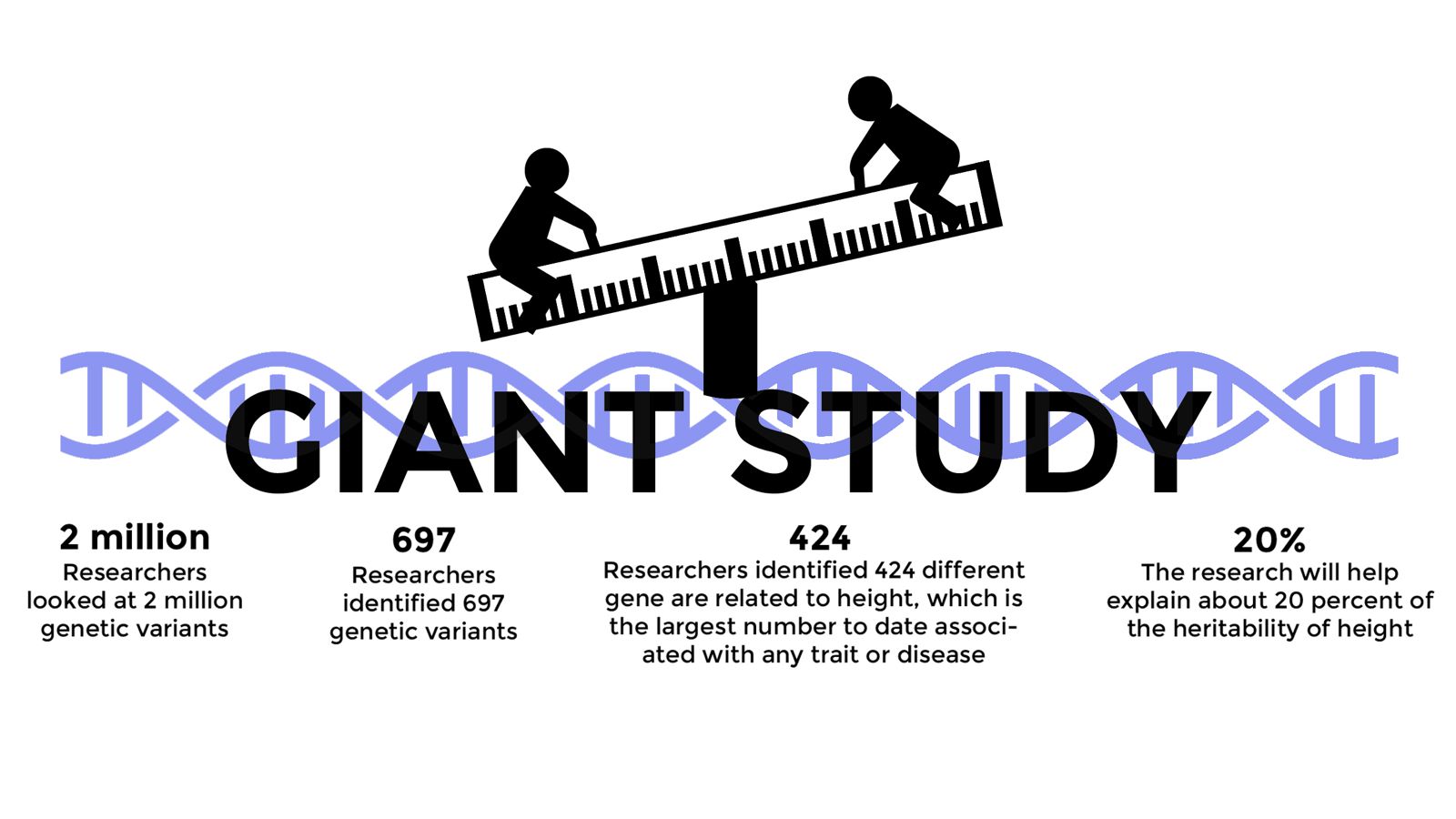

Created by the Genetic Investigation of Anthropometric Traits (GIANT) Consortium, which strives to identify the genetics behind human shape and body size, the study comprised of more than 300 institutions and more than 250,000 subjects, making it the largest genome-wide association research endeavor to date.

“When you double the sample size and increase your statistical power, you can make new discoveries,” Hirschhorn said. “As you study more people, you are going to learn more about biology.”

By sharing and analyzing the genomic code of the large sample, the team of researchers was able to pin down genetic variants in relation to height and in turn, draw definitive conclusions about how and where DNA defines height.

“We identified 400 different regions on the genome, each of which contains one or more genes that is important for skeletal growth, for height,” Hirschhorn said. “And those all add up together to regulate height.”

He said, as a pediatric endocrinologist — a doctor that focuses on diseases related to the glands, such as diabetes — he hopes to identify treatments for abnormal skeletal growth, such as severe short stature.

“The main reason that children come to see a pediatric endocrinologist is that they’re not growing well, so their parents are worried,” Hirschhorn said. “Sometimes, that’s due to genes…and that’s where the study can identify all the genes that affect height and growth, which can then be used to indicate when there is a more severe problem.”

The result of the study was the astonishing identification of 697 genetic variants, located on 424 gene regions that are related to height. The study, published on Oct. 5 in Nature Genetics, stated that height is the most genetically understood human trait, which Hirschhorn predicts will make it a model for further inquiry into a variety of medical fields.

“There are many spinoffs of what genetics are used for as ways of identifying history or how things work,” said Lindsay Farrer, chief of the biomedical genetics program at the Boston University School of Medicine.

And in this GIANT case, a fair “spinoff” is the continued study of various human diseases, which, according to Farrer, goes hand-in-hand with genetics.

“Even before the individual has developed anything in terms of a body, skeleton or any true life, the DNA sequence has already been set,” he said. “It [the DNA sequence] is the most upstream event. If you are thinking of the disease or where it all began, it is [in] the human DNA.”

BUSM is also playing its role in harnessing the potential of genetics. The genetics department is currently researching the genetic role in everything from drug dependence to dementia, Farrer said.

“Some people, like myself, are studying human populations as a way to identify genetic causes of disease,” he said. “Other members of our faculty are studying inside cells or human tissue or model organisms to better understand the genetic bases of disease.”

Genetic research will continue to expand greatly over the next 50 years, Farrer said, making for dramatic renewal of “what we know today.”