Cultural organizations offer opportunities for people to come together to seek a better understanding about the world and its respective cultural practices. On a college campus, a cultural institution could serve to create a network of students engaged with the culture and establish mutual respect for each other.

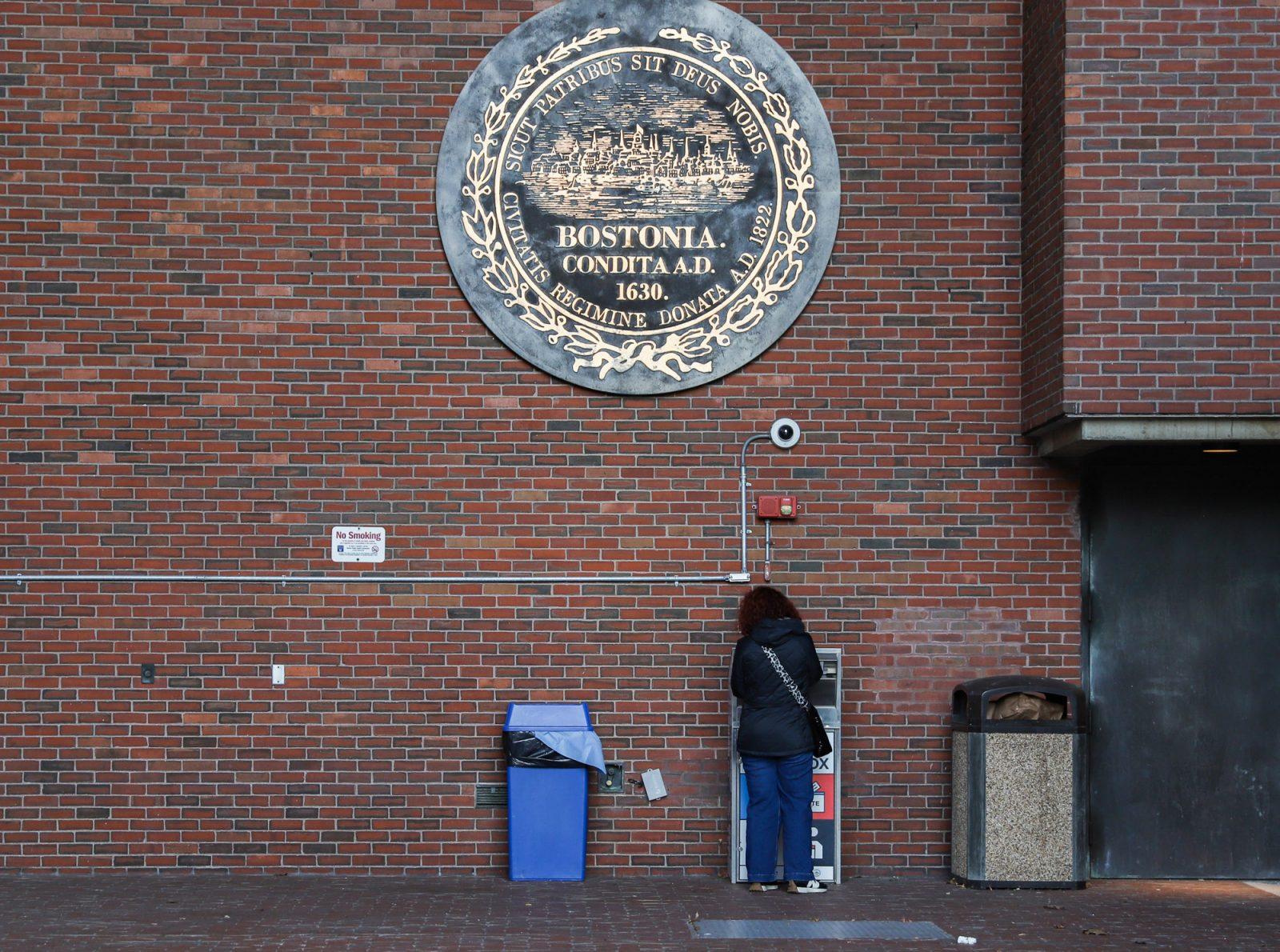

The Confucius Institute, a cultural institute run by the Chinese government, has recently come under attack by members from the University of Massachusetts Boston community for what some see as actions infringing upon academic freedoms and implementing censorship. A coalition of 17 frustrated students, teachers and alumni have written a letter addressed to the university, explaining their accusations and demanding a meeting in hopes of shutting the center down on campus.

The Institute operates on several college campuses across the country and provides a myriad of opportunities for students to interact with Chinese culture, offering supplemental language and cultural courses as well as grants for students to study in China.

While those opposed to the institute raised concerns about ways it has censored information, they don’t seem particularly justified in their stance to expel the center from campus. In fact, direct instances of the Confucius Institute of censorship seem rare according to an article published Tuesday in the Boston Globe. Besides its potential responsibility for canceling a talk with the Dalai Lama in 2014 — which upset many advocates of academic freedom — the Confucius center does not seem to endorse censorship.

However, the institution’s affiliation with the Chinese government does raise suspicions about the purpose of such a center on an American campus, especially in an urban setting like Boston. In fact, the center almost resembles an embassy, undermining its purpose as a center for learning and cultural exchange.

It’s no secret that China has had an extensive history with communism and continues to engage in parts of the political philosophy today. It’s also no secret that the United States has always stood firmly against communist ideals and has taken threats to democracy seriously. It’s only fair to ask if this pushback might stem from an anti-communist hysteria. The word “communist” seems to elicit the same dramatic reaction it received back during the Red Scare. Most of the grievances voiced by the 17-member group from UMass Boston dealt with Chinese issues generally, not those specific to the institution. Thus, it is important to distance the organization from past connotations of communism.

Nonetheless, it is important to note that similar types of centers found across the country have been successful in establishing a link between cultures and providing an international haven for the community. However, these institutes, while sometimes still overseen by their respective governments, do not operate on college campuses.

Thus, the Confucius Institute operates in a distinct and unusual way as compared to its counterparts. UMass Boston contributed nearly a fifth of the center’s budget for the year. But there does not seem to be any system in place for the university to oversee what curriculum the center decides to teach. The center seems to be entirely in charge of the material they’re teaching students. This does create the potential for misinformation or skewing of important events. The university holds no approval power in the center’s curriculum, which could be problematic, considering its substantial funding.

In the letter written by the objectors, the Institute came under fire for skewing facts of certain historical events, including the protests at Tiananmen Square. If the Institute truly is skewing the teaching of these kinds of key historical events to the point that they stray from the truth, it would be unacceptable.

All in all, despite the benefits this center has to offer students, the number of suspicions raised by the center seems to clash with the educational purpose of the Confucius Institute. In order for centers like these to function successfully on American college campuses, they must be structured in a way so as to serve students appropriately and in a way that enhances their learning. Otherwise, these centers would prove to be unnecessary additions to universities that already teach a variety of perspectives.

In order for these institutions to make a lasting impact on their students, they must consider ways to increase transparency, particularly for the colleges they’re operating on. An institution responsible for the dissemination of information without careful consideration could be dangerous. Universities should also work to institute systems to prevent misinformation. UMass Boston might benefit by requesting to review the Institute’s curriculum and granting them approval to teach the material.

A cultural organization run by a foreign power is concerning for reasons beyond the structure itself. The last thing we want is a higher education institution entangled in a case with the Chinese government or any foreign government for that matter.