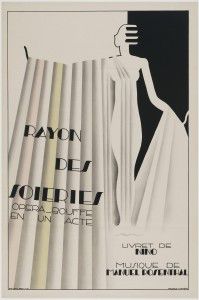

Maurice Dufréne’s “Poster for the Comic Opera, Rayon des Soieries, The Silk Counter” (1930)

When walking the Museum of Fine Art’s halls, the recently added “Art in the Street: European Posters” exhibit immediately sticks out among the oil paintings of stuffy Victorian royals and pristine marble statues of the female form. And with good reason – “Art in the Street” isn’t just trying to catch the eye of the viewer. This exhibit is art with a purpose. This art wants to sell you something.

“Art in the Street” features a number of advertising posters from early 20th century Europe. Rooted in the 1890s, these posters appropriated the fine art that had only been accessible in elite museums and salons and brought it to the streets and store windows of France, Germany, Switzerland, Russia and the Netherlands.

The exhibit incorporates well-known poster artists like Pierre Bonnard and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec with those from Northern Europe who may not be as familiar to the casual viewer.

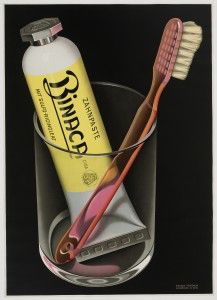

A far cry from the loud, flashy advertising plastered on MBTA buses or billboards over Kenmore Square, the posters displayed in “Art in the Street” are softer, quieter – yet no less alluring. Used to promote everything from operas (Maurice Dufréne’s “Poster for the Comic Opera, Rayon des Soieries, The Silk Counter,” 1930), art expositions to toothpaste (Niklaus Stoecklin’s Binaca [Toothpaste and Toothbrush], 1941) and alcohol, the posters display a level of finesse that has been all but lost in the modern advertising world so reliant on technology and computer-generated images.

Niklaus Stoecklin’s “Binaca” (1941)

The exhibit even features several examples of photomontage, most notably in Anton Lavinsky’s movie poster for the Russian film “Battleship Potemkin,” which features a photo of a black and white soldier over two menacing battleship cannons on either side, all against a striking yellow background.

“Art in the Street” also ventures into a more simplistic realm, featuring several Swiss “object posters.” Peaking in popularity during and after World War II, these posters dismiss text in favor of bold depictions of a product. Swiss artist Niklaus Stoecklin did this best in his 1941 poster featuring only a bright pink toothbrush and a yellow tube of Binaca toothpaste in a clear glass.

The exhibit ultimately lives up to its name. Visiting “Art in the Street” feels more like strolling the streets of a turn-of-the-century European city than walking through a museum. Each poster, unique in its content and style, is not only promoting a brand or a ticket to a theater performance, but also promoting the idea of art’s universality — the idea that it should not be limited to those who can afford to access it.