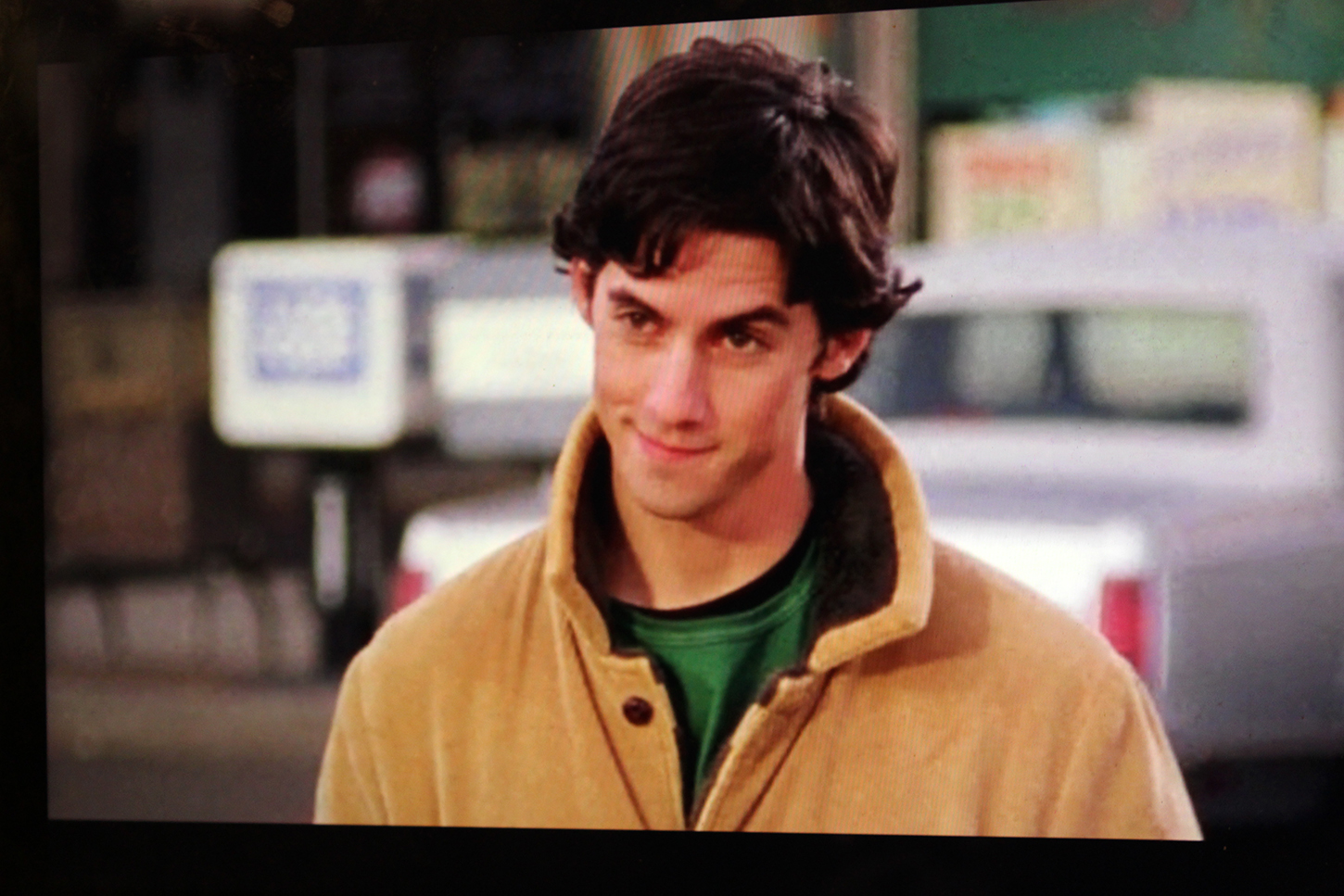

Ryan Gosling plays a speed racer in upcoming film The Play Beyond the Pines.

It is strange to be in the same room as Ryan Gosling, but indeed much stranger to find the man sitting next to Gosling far more interesting.

Derek Cianfrance, widely recognized, but only recently, for his neorealistic filmmaking in the acclaimed Blue Valentine, sat in our interview eager to prove the triumph of method acting, to honor the courage of cinematographer, Sean Bobbitt, and to encourage jaded moviemakers to push the boundaries of conventional film.

Cianfrance is again in the spotlight with The Place Beyond the Pines, an unapologetically genuine look at legacy in the faded town of Schenectady, NY. Cianfrance’s commitment to authenticity is unmistakable and palpable onscreen. But his surprising methodology to weave story, acting, photography in a purposeful construct — an epic — became clear in speaking with him and the Pines cast, including Gosling, Eva Mendes, Dane DeHaan and Emory Cohen in Manhattan last month.

But before revealing his directorial secrets, Cianfrance initially disoriented a room of reporters – he attributed his filmmaking process to racecar driver Danica Patrick.

“She always knew how fast she could drive,” Cianfrance recalled. “She would always drive that fast, but then she’d drive a couple more mph over the speed in which she felt in control. And that meant, oftentimes, she would crash. But by crashing, she

would also push her own boundaries and get better.”

Cianfrance does indeed drive far over the Hollywood speed limit in Pines. When literal speed racer, Luke (Ryan Gosling) discovers that he has fathered a child with the destitute Romina (Eva Mendes), he begins to rob Schenectady banks to provide

for his son. His string of heists entangles him with Officer Avery (Bradley Cooper), condemning a friendship that their two sons, Jason (Dane DeHaan) and AJ (Emory Cohen) will form in the future.

Perhaps even more risky, however, is that the triptych epic, encompassing three individual periods in time, unravels chronologically, a style virtually unheard of in modern day film. But for Cianfrance, it was the only way to communicate the importance of legacy in Pines.

“Structure is really important to me, to do it in this chronological order… to talk about American legacy and everything that doesn’t go away,” Cianfrance explained. “I wanted this film to have a Biblical feeling to it.”

Cianfrance faced plenty of opposition in designing the film to be chronological, Gosling recalled.

“Everybody told him to cut it and to change it and not to do it that way.,” he said. “I think everyone assumed that he would eventually cave in the edit and he didn’t. He’s the most stubborn man of all time.”

Cianfrance’s directorial strategies are risky too, especially in his exploration of method acting, a performance style that allows actors to absorb rather than project the qualities of their characters. Cianfrance encouraged Mendes, whose character Romina works at a sleepy Schenectady diner, to work as a waitress to find inspiration.

“I got to know the women that worked there and I heard some amazing stories. They were born and raised in Schenectady … it really helped me get into my role. [The customers] were hungry, they wanted their food and they wanted it fast. And if I didn’t get it to them, they would not leave me a tip,” Mendes said.

“It was a common complaint that she didn’t put enough salt on the French fries,” joked Cianfrance.

While this type of method acting has been practiced to obtain authenticity onscreen for decades, Cianfrance pushes his actors to race at even higher miles per hour. At these high speeds, not only do Cianfrance’s actors experience life as their characters,

they get the opportunity to make serious film decisions.

When it came time to cast, Mendes was allowed the final say in who would play her mother, Malena (Olga Merediz), a strong supporting role in Pines.

“I hung out with fifteen amazing women [during the casting process],” she said. “The last person came in … [and] had all of these qualities that my real mother has. I immediately felt this connection with her. I called Derek and said, ‘So I found this lady, you want to watch her tape?’”

“And he said, “Okay, then she’ll play your mother, ”’ Mendes remembers.

“I still can’t believe that [he] gave me that freedom. It was incredible. Derek provides this environment for you; it’s so realistic that it feels like you’re watching a documentary.”

Similiarly, Cianfrance’s insistence on realism forced Gosling to truly encapsulate motorcyclist Luke’s experience.

“I was creating this guy who was a melting pot of all of these masculine clichés: motorcycles, tattoos, guns, knives, muscles. And [in preparing for Pines] I had this face tattoo … I regretted immediately,” Gosling said.

“I said to Derek, ‘I can’t do this, I look ridiculous. It’s going to ruin your movie,’” he said.

“And he said, ‘That’s what happens when people get face tattoos, they regret them. This movie is about consequences and now you’ve had to pay for what you’ve done,’” quoted Gosling.

“I felt so much shame about doing that, that I had taken it too far and I was going to ruin everything … I couldn’t look at myself in the mirror…I had this shame that I don’t think I could have acted…[it] gave me a connection to the character that I don’t

think I would’ve had. Because when I was holding this [baby], I felt ashamed that I was his father, that I was this person that I had chose to be. It was a gift from Derek that I never could have planned.”

Harkening back to Danica Patrick, Cianfrance acknowledged the high speeds he requires of his filmmaking team.

“I ask my actors [and crew] to crash for me, although not on a motorcycle, and fail. And if they can do that, then, all of a sudden, there’s no more judgment,” he said. “They can succeed greatly because it’s okay to fail.”

Cianfrance’s encouragement to crash and fail in order to heighten realism only intensifies in Pines’ cinematography. While visceral camerawork penetrates throughout Pines, it is particularly palpable in the film’s opening scene. To introduce the danger of motorcyclist Luke, Cianfrance and cinematographer Sean Bobbitt follow Luke from his trailer, through circus grounds, into an arena tent, and then to the cage of three motorcycles, “The Globe of Death.”

“We thought that we needed to start an epic movie off with an epic opening shot like so many of our favorite films, like Touch of Evil…constantly revealing something new, you’re going to learn some things as this shot unfolds. Sean [mirrors] the

physicality of the actors [when he shoots] … he kind of floats in a way, it’s beautiful,” he said.

But cinematographer Sean Bobbitt wanted to take Cianfrance’s commitment to reality one step further … to film inside “The Globe of Death.”

“I said it was crazy,” insisted Cianfrance. But Bobbitt insisted on the persistence of reality in Pines. “’No, we must go to the center,” Cianfrance remembered Bobbitt demanding.

“So Sean [followed] in the cage. And there are beautiful images of throttles, revving … the motorcycles start spinning around Sean; it’s abstract and visceral and beautiful. And all of a sudden, my monitor goes static.”

After the magnificent long take. Bobbitt had been knocked to the ground by the motorcycle. And after his dogged insistence to chance a second attempt, he was hit again, this time by a falling motorcycle that had stalled in mid air. Bobbitt was seriously concussed and Cianfrance shut down the shoot until Bobbitt recovered.

“He was so mad at me for not letting him go back in the cage [when they resumed filming],” Cianfrance said. “He still doesn’t really return my phone calls.”

And so in the case of cinematography, Cianfrance did indeed crash. But in doing so, Cianfrance only redrew the boundaries lines, the mph, that The Place Beyond the Pines had to surpass.

But why such commitment to realism? Why spend years (Cianfrance tinkered with the script before, during, and after his creation of Blue Valentine) constructing story, performance, and camera work, only to lose that careful construction to overwhelming realism?

“I wanted the audience in this movie to be alert and to be active. I wanted their imaginations to peak because I want them to be watching the movie. I don’t want them to sit back,” insisted Cianfrance.

In story, performances, and cinematography, The Place Beyond the Pines indeed snaps audiences to attention, its visceral authenticity forcing audiences to be alert and active. And just as he painstakingly directs his cast and crew, Cianfrance too directs his audiences. He makes them drive just that little bit faster.