With lives at stake, methadone clinics play an integral role in treating opiate addicts.

However, the actions of city and state government, insurance companies and private equity firms may impose financial difficulties on patients seeking opiate addiction treatment.

Last month, Massachusetts Gov. Deval Patrick declared opiate abuse a public health emergency in Massachusetts, citing potent painkillers as gateway drugs for heroin and the high numbers for deaths due to opiate overdoses as reasons.

“Heroin today is cheap and highly potent. The use of oxycodone and other narcotic painkillers — often as a route to heroin addiction — has been on the rise for some years now,” Patrick said in an official statement. “At least 140 people died from suspected heroin overdoses in Massachusetts in the last several months, levels previously unseen. From 2000 to 2012, the number of unintentional opiate overdoses increased by 90 percent — affecting all kinds of people from all kinds of neighborhoods from all around the Commonwealth. For most of those who received services from the Bureau of Substance Abuse Services in 2013, opiates were their drug of choice.”

Boston Mayor Martin Walsh also addressed this issue on the city level.

“I don’t want to get another call from a mother or a father who is in fear of losing their child, because of a habit that began with pills from a neighbor’s medicine cabinet,” Walsh said. “Substance abuse requires comprehensive approaches that include prevention, intervention and treatment. But if we can get these unneeded drugs out of our neighborhoods, we will be taking a step in the right direction.”

Yet, amid this opiate epidemic, Boston’s only public methadone clinic, which dispenses methadone as a treatment for opiate abuse, is poised to cease operations in early summer, according to Nick Martin, communications director for the Boston Public Health Commission. Patients will be assisted by the BPHC in their transition to a for-profit private clinic called Community Substance Abuse Centers, Martin said.

“The process will, in terms of transitioning clients, will likely happen sometime in the early summer, late May, early June. The new fiscal year for the city starts on July 1, so the goal would be to have all those clients transitioned by July 1,” Martin said.

According to Martin, transferring clients from the 40-year-old city-run clinic to a private provider would improve care for patients, in addition to saving operating costs for the BPHC. Funding for the clinic that was allocated to the city’s budget this year was $300,000 and overall expenses exceed $2 million.

“The cost of running the clinic has risen over time for us … It costs about $2.4 million last fiscal year to run,” Martin said. “We think those resources could be better directed to another area.”

Walsh proposed an Office of Recovery Services that would assist patients in their recovery, Martin said.

“That office will really help find the gaps and holes in the treatment network within the city of Boston, it will help better coordinate access to the resources that are available.”

Though the BPHC aims for as smooth a transition as possible, the implications of transitioning patients from the sole public methadone clinic in Boston to private clinics may be dire if not executed well, Joji Suzuki, associate psychiatrist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, said.

“It is concerning because they have a whole history behind it and if it is transferred to a different organization, it is not clear that the same caliber of treatment is going to be offered … I hope the people who are making these decisions are doing it carefully, responsibly, with patients in mind,” Suzuki said. “I trust that the DPH [Department of Public Health] will do the right thing but we will have to wait and see because it happened so quickly … It’s not a lot of time to actually put things into place so I think a lot of people are nervous that things may get worse for this patient population.”

The patients BPHC currently serve will have the option to continue treatment at the center BPHC is coordinating with or to continue treatment elsewhere, Martin said. There are currently four private methadone clinics operating in Boston. The regulations that govern methadone restrict easy access to the drug; methadone can only be dispensed in federally licensed, federally regulated clinics, Suzuki said.

One of these private methadone clinics is Bay Cove Human Services, a nonprofit center that is funded by public health money, which means that the uninsured would be able to access treatment, according to Elizabeth Bredin, senior program director of Bay Cove Human Services.

“Most of it’s covered by Medicare and Medicaid and some people are self-pay and then it is around $100 and $130 a week for medication and therapy and they get a lot of therapy.”

Bredin said she sees patients of varying socioeconomic backgrounds, ranging from the homeless to those who have stable jobs.

“One in three people are working and earning good salary and have their lives working pretty well once they get stabilized on the medication and then we have a wide variation in terms of people who are on Medicare, Medicaid and public health money, depend on public health money … We have an increasing number of young homeless people, young homeless families.”

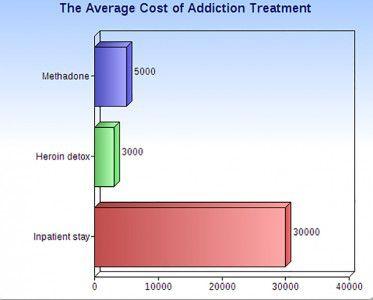

However, not all methadone clinics are nonprofit centers such as Bay Cove Human Services that have public health funding. For opiate addicts without insurance, or even for those with inadequate insurance coverage, obtaining opiate addiction treatment could be challenging.

While methadone treatment is generally paid for through MassHealth, according to Anne Roach, media relations manager for Massachusetts Department of Public Health, methadone is not the only available treatment option.

Another treatment on the market is buprenorphine, which can be prescribed by the patient’s physician, Suzuki said.

“Buprenorphine treatment for example, not every insurance company covers it adequately. So for buprenorphine, for example, if a patient had to pay out of the pocket, it might be $200 to $300 a month, which is a lot of money. So we need better insurance coverage for these medications and we need to make sure they cover for addiction treatment as well. So the cost burden can sometimes be really high; it can be prohibitive,” Suzuki said.

Although some insurance companies do not adequately cover addiction treatment, Massachusetts’ largest insurance company Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts decreased the number of painkiller prescriptions by 6.6 million in an effort to curtail the opiate epidemic. However, there are complicated financial implications for the pharmaceutical industry as a result of limiting the supply of painkillers.

“There’s financial implications for the pharmaceutical industry. Which might also mean that supply, as it gets lower, one potential consequence will be that more people would migrate to heroin,” Suzuki said. “For example, if Vicodin, Percodan and oxycodone are less available on the street, overall addiction rates might go down but it might mean that those who can’t stop using might end up using more heroin.”

With an increasing number of patients seeking treatment for opiate addiction, the substance abuse industry is worth $7.7 billion, according to IBISWorld Inc. The largest chain of substance abuse treatment centers is Habit OPCO, which operates 13 clinics in Massachusetts, treating 860 people daily and charging $135 a week for methadone treatment. Bain Capital seized the opportunity to invest by acquiring Habit OPCO through CRC Health.

David Rosenbloom, professor of health policy and management at the Boston University School of Public Health, said that the chief motive for Bain Capital’s investment is profit.

“Bain Capital obviously thinks it can make money in the methadone business. And as a general rule, Bain Capital’s acquisitions of companies tend to wind up putting big debt on the companies that they acquire so they can get their money out quickly. It’s a business model that I don’t happen to like,” Rosenbloom said.

Suzuki said that Bain Capital’s acquisition of Habit OPCO may spell negativity for patients, who will receive lower quality care as a result. Habit OPCO may find ways to profit by finding ways to generate the maximum revenue at the lowest operating cost.

“Bain purchasing Habit OPCO is extremely concerning in my mind,” Suzuki said. “I was very upset to hear that because Bain is simply doing what they do, which is to maximize profits for their shareholders. They are not necessarily going into this because they deeply care about patients on methadone.”

Suzuki said this change in structure can harm patients.

“It’s very, very concerning because on the one hand, they are seeing this as an opportunity to make profits and I think they are correct in that sense that this is likely a financial opportunity,” she said. “But on the other hand, healthcare should not be seen from a profit motive. We really need to be seeing healthcare from a human rights perspective and a humanistic perspective. We should not be making a profit out of healthcare.”

John Mark Blowen APRN • Jun 5, 2014 at 12:42 pm

Under the ACA and the mental health/substance abuse parity law (signed into law in 2008 and supposedly in effect since Jan 2010 ) are not all health insurance policies, that have a mental health or behavioral health rider, legally bound to pay for medication assisted treatment ?

We may be a ways away from being able to accept a patients Blue Cross card, but I know of one patient in NH who is being reimbursed 80% by his federal BC/BS plan.

It will no doubt be a struggle to get the health insurance industry to step up, but I think there may be hope.

M. Menius • May 12, 2014 at 4:12 pm

There is a balance that exists between providing a medical service for profit and maintaining a quality standard of care that places real value on people’s lives. I have seen it done well and also done poorly. Methadone, or any “medication-assisted treatment”, that is not provide within a larger context of recovery and supportive counseling is not particularly helpful. With management of one’s opioid withdrawal, there should come the expectation of behavior, attitude, and lifestyle change.

A better parallel is someone who is dangerously overweight but who refuses to adjust their eating habits or adopt exercise. The cost of “treating” such a person will only go up and at some point they should assume responsibility for better self-care. Same with addiction recovery, counseling and lifestyle change must accompany the medication assistance.

Anonymous methadone client • May 5, 2014 at 10:13 pm

What about clients on methadone and these clinics like CSAC do not accept ANY private insurances? Forget about the clients who have put their lives back together by being on a HARM reduction treatment like methadone and now they have to pay $125 a week and $500 to see a doctor? I am trying to establish a savings but paying a mortgage and now having to pay at least $500 monthly for methadone tx… What about us?

More Info • Dec 12, 2015 at 2:36 am

Hello there! I could have sworn I’ve been to this website before but after going through a

few of the posts I realized it’s new to me.

Nonetheless, I’m certainly happy I found it and I’ll be bookmarking it and checking back frequently!