With global concerns about epidemic and infectious diseases increasing, Boston University School of Medicine researchers have developed a method to identify viruses behind hemorrhagic fevers similar to Ebola before they become symptomatic, according to a Thursday study.

Ignacio S. Caballero, an author of the study, said the results might lead to treatment of Lassa and Marburg fevers during their early stages when treatment is most effective.

“What we found were a series of genes that show a unique pattern of expression depending on the type of virus that has infected the individual,” said Caballero, a graduate student in BUSM. “The implication is that the unique pattern comes up before we can detect the actual virus in the organism. So it precedes current methods for detecting the disease.”

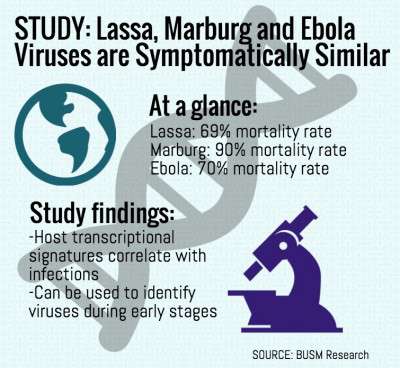

An estimated 100,000 to 300,000 cases of Lassa occur every year, and over 20 individual cases have reached the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom and Japan since 1969, according to the study. The mortality rate of Lassa is 69 percent and close to 90 percent for Marburg fever.

Caballero said a major holdback in creating effective treatment for viruses like Lassa, Marburg and Ebola, is that all of their flu-like symptoms are very similar.

“Right now, one of the confounding factors is that Lassa virus is an epidemic pathogen in that area, so the early symptoms of both diseases, Ebola and Lassa, look very similar,” he said. “One of the first things that has to be done when screening for samples that may have been infected with Ebola is to rule out existing pathogens like Lassa.”

The research took place at the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute for Infectious Diseases due to the contagious nature of the viruses, and the analysis that followed took place at BU, Caballero said.

Caballero said the study is just one step toward finding cures for viruses like Ebola.

“There’s a lot of work that needs to be done,” he said. “For now, these are preliminary results in a controlled setting in a lab, so we’ve been able to see unique patterns of different viruses. In order to implement it in the field, we would have to get more data. Specifically, trying it on humans, and also with additional species.”

Several students said they are hopeful about how the research will help address hemorrhagic infectious diseases.

Brad Kutler, a junior in the School of Management, said he was interested to hear about the research and thinks that BU’s involvement with this type of research gives the school a good reputation.

“Whenever BU does this kind of stuff, it makes me feel like I go to a university that is so involved in cool breakthroughs,” he said. “It gives my school a better name, and it’s awesome.”

Karl Thompson, a graduate student in the School of Education, said the study is good news, not just for Ebola treatment, but for treatment of all prevalent viruses.

“Largely Ebola, Colera and a lot of other viruses and bacteria don’t generally affect more affluent populations because of sanitation,” he said. “Here, we can contain it. But research in virology and anything with bacteria as well — that can apply to AIDS or anything that’s related. So of course, you learn about Ebola and a lot of subsidiary issues too.”

Graham Arrick, a senior in the College of Engineering, said the research is helpful, but he is not sure what sort of impact the findings will have.

“It takes a lot more than figuring something out to implement it,” he said. “If you figure something out, that’s great. But if no one pays attention to you, then it’s worth something to you, but not to the rest of the world. Do I think it’s hopeful? Yes. If there was a vaccine that existed and was being mass-produced, then I would feel a lot more hopeful.”