About 79 million Americans are currently infected with human papillomavirus, a commonly overlooked sexually transmitted infection, with an estimated 14 million more infected each year, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Inevitably, these numbers beg the clinical question: How can HPV be prevented?

“As an HPV researcher, I look at all the literature that comes out on the harms of HPV, on the effectiveness of the vaccine,” said Rebecca Perkins, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Boston University’s School of Medicine. “If everybody knew what I know, the vaccination rates would be 100 percent.”

Patients entrust their providers to give health recommendations, Perkins said. Such open lines of communication can cause a positive domino effect regarding the prevention of HPV’s harmful effects.

“HPV is the cause of 27,000 cancers in the United States every year and some of the cancers you can screen for, like cervical cancer,” Perkins said. “HPV vaccination will help prevent cancer and will also help prevent women from needing to undergo painful procedures to prevent the development of cancer.”

Perkins co-authored a study in the journal Vaccine focused on health care-provider-focused interventions, according to a Nov. 24 press release. Interventions included repeated contacts, education and individualized feedback from doctors and nurses — all of which were found capable of increasing HPV vaccination rates.

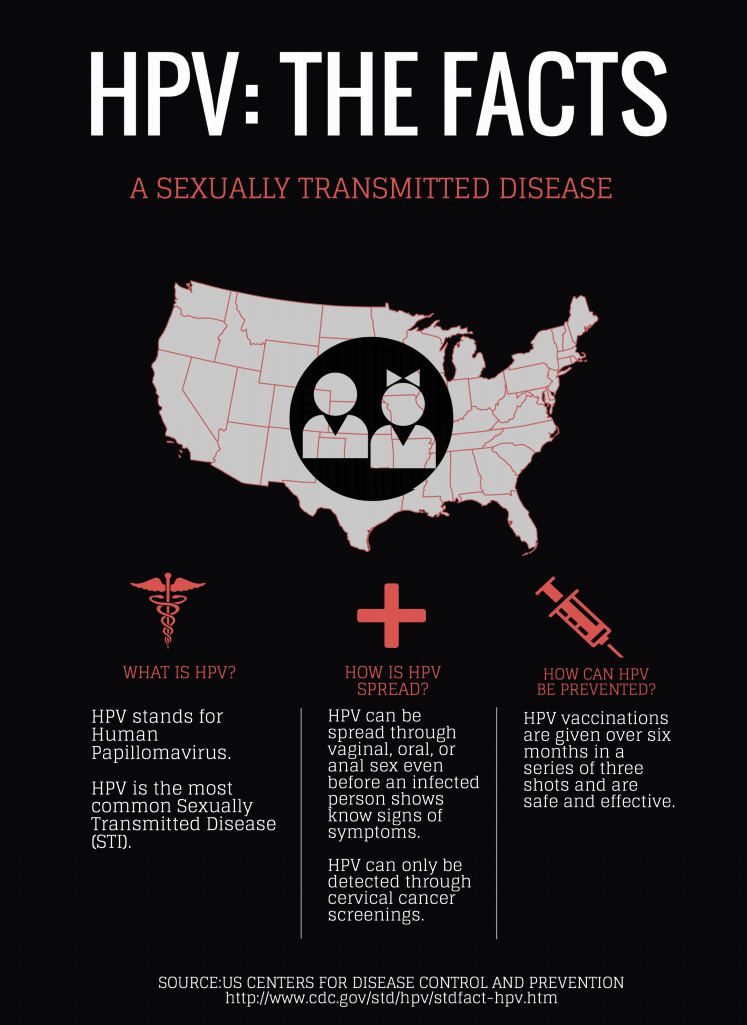

Though most sexually active men and women will get at least one type of HPV during their lifetime, getting vaccinated decreases the risk of contracting complications from HPV such as genital warts and the development of some cancers, according to the CDC.

Perkins said the HPV vaccination rate in the United States remains below the national target of 80 percent. As a practicing gynecologist, she said on an average day at her clinic, 20 percent of her time is spent dealing with the consequences of HPV infection.

This study’s results reinforce a long list of research in support of intervention impact, specifically physician-to-patient dialogue, Perkins said.

“Provider recommendation has been shown, in almost all studies, to be the most important factor in vaccinations,” she said. “If the doctor says, ‘you need to get three vaccines, the HPV and the tetanus and the meningitis’ and they explain why, most people follow their doctor’s advice.”

Going along with this strategy, Li Liu, a freshman in the College of Arts and Sciences, said the patient-provider relationship is key to boosting HPV vaccination rates since patients often lack the knowledge their health care providers have.

“Patients listen to their doctors,” she said. “If your doctor encourages you to do so, you will follow the doctor.”

In addition to physician recommendation, continued education carries equal weight, said Briana Swift, coordinator of Peer Health Exchange at BU and a dual-degree junior in CAS and the School of Management. Research on HPV is key to raising HPV awareness.

“Many teens are at least vaguely familiar with STIs [sexually transmitted infections], such as herpes and chlamydia. However, HPV is consistently the STI that most teens know the least about, which is surprising because it is so very prevalent,” she said. “Publishing results of HPV research and ensuring that these results are shared with the younger population is a step in the right direction.”

As a national nonprofit organization that aims to provide comprehensive health education for high school students, PHE at BU has addressed HPV in its workshops for the past 10 years, Swift said.

“Peer Health Exchange has transferred from a topic-based to a skills-based curriculum, but continues to address HPV in workshops that address skills such as accessing resources, communication and decision making,” she said. “Teens are provided with reputable resources from PHE to consult regarding HPV.”

Moving forward, Perkins said she hopes provider-focused interventions could be implemented in more clinics, emphasizing the importance of the provider’s role in prioritizing conversation over HPV.

“Doctors have a lot to accomplish in their 15-minute visits with patients and… a lot of times, HPV vaccinations get delayed and forgotten,” she said. “Helping providers understand HPV vaccinations and why it’s important is the most effective way to recommend. It will really be the key to approaching the 80 percent [vaccination rate] mark.”