Despite government data showing that the number of animals for experimental use has decreased over the past 15 years, the total use of animals has increased in top research institutes, according to a Wednesday study by the animal rights group People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals.

The study suggests that government data contains “limited figures” that do not account for the species excluded from the Animal Welfare Act. AWA includes dogs, cats, non-human primates and other larger mammals in the statistics, but excludes mice, rats, amphibians, fish, birds and agricultural animals bred from experimentation, the study stated.

“It’s a huge embarrassment and really scandalous that the United States is the only country in the industrialized world that doesn’t have solid documentation on how many vertebrate animals are used in laboratories,” said Alka Chandna, one of the authors of the study.

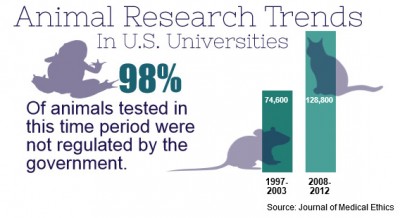

The average total number of animals used for research increased from 74,600, from 1997 to 2003, to 128,800, from 2008 to 2012, the study stated. For 98 percent of animals tested during this time, there were no federal regulations to govern the way they were treated.

“This flies in the face of what the government has been saying about animal use,” Chandna said. “They have been lying. They have been saying animal use has been going down, and this placates the public and pulls a wool over people’s eyes.”

Research institutes funded by the National Institutes of Health must report the average numbers of all vertebrate animals used, the study stated. PETA requested the documents of the top 25 recipients of NIH funding to conduct their research.

Chandna said one underlying reason for the increase is that funding is highly skewed toward animal use rather than the development of alternatives. She said Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging is one noninvasive and pain-free tool that can be used to understand which areas of the brain are affected by pain.

James Levin, animal containment expert and director of Lab Animal Services at Boston University, said there has been no significant increase in animal use at the school’s laboratories.

“This increase in usage was caused by increased funding by the NIH in animal research. I suspect that the animal usage per investigator has in fact decreased during this same period, but the study made no attempt to analyze that question,” he wrote in an email. “Funding by NIH has been done for the last two years, and we have seen a corresponding reduction in the [overall] use of animals at BU.”

Levin said there has a been a shift away from using larger animals, such as dogs and cats, to using mice because they can be used “to answer very specific research questions.”

Brent Vogt, a research professor at the BU School of Medicine, specializes in neurological pain and uses mice in his research. Vogt works in BMC’s Department of Anatomy and Neurobiology and said animals are fundamental to research.

“There’s a huge monumental need for curing disorders like neuropathic pain and inflammatory pain, and these problems cannot be addressed without animal research,” he said.

Vogt said his kind of research is supported and heavily regulated by the NIH and the U.S. Department of Agriculture to ensure the well-being of society animals.

“It should be said that this is heavily overseen by the USDA, particularly for use of rabbits and monkeys, so it’s not like we’re not heavily regulated,” he said. “There are protocols, and we have to follow the protocols, which is just fine. It’s not pain for its own sakes. The animal rights groups, PETA, seem to have this notion that we enjoy doing this, which is absurd. We don’t.”

Chandna said 80 percent of lab mice and rats are not given post-experimental pain relief.

“If you look at the ethological research of mice and rats they phenomenal animals too,” she said. “They are empathetic, they are intelligent, they are very social, they lead emotionally rich lives, but that an understanding of those animals that hasn’t yet filtered down to the public, so there is less concern for those animals by the public and those experimenters.”