The Ebola outbreak that grew rapidly last year has claimed 9,729 lives as of Saturday, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Approximately 99.8 percent of those deaths are from Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone. While the rate of new cases being declared has decreased, the question scientists are still facing is how to diagnose cases more efficiently.

Massachusetts Institute of Technology researchers announced on Feb. 24 a development for a new test for Ebola that functions similarly to a pregnancy test, using samples of blood to detect the virus within 10 minutes, allowing for more rapid diagnosis.

There is no sample preparation required, said Lee Gehrke, professor of health sciences and technology at MIT and author of the paper that details the new technology, which drastically reduces result time compared to existing tests.

“You simply take a few drops of blood … and it’s just a body fluid that is applied to the test and you run the test, so there is no lengthy sample prep needed,” Gehrke said.

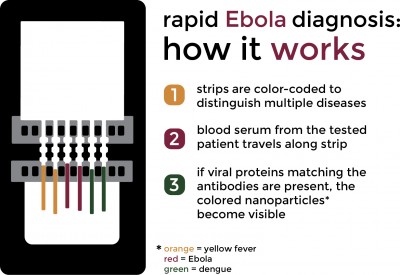

The device, which can also detect dengue fever and yellow fever, uses lateral flow chromatography, meaning the paper will turn different colors depending on the disease the patient has. On the paper, there are nanoparticles linked to antibodies that recognize Ebola, dengue fever and yellow fever. If the ligand — the protein being tested for — is present, it binds to the nanoparticle until it hits the spot on the paper where the second antibody is painted. The antibody will grab the nanoparticle and accumulate until a line is formed that is visible to the naked eye.

People administering the test do not need any kind of special training, Gehrke said. The simplicity of the test translates to effectiveness.

“You also don’t need power, refrigeration, special chemicals,” Gehrke said.

And though the test is much faster than other methods, such as polymerase chain reactions that currently are used and can take up to three days, Gehrke said it is just as accurate.

Currently, the lateral flow test is in the process of being approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Though it is not yet approved for individual use, Gehrke said it can still be used to sample populations.

While Gehrke and his collaborators want the test to help individual patients, it could also have a broader application in terms of public health.

In addition to the test, they have also been working on a companion mobile phone app. The ultimate goal, he said, is to create testing devices that can be used in the home so samples can be taken and the data can be transmitted by mobile phone. The data would then be transmitted to Google Maps, which would help track where epidemics are breaking out and how the diseases are moving across populations.

“The important distinction is these are real data,” Gehrke said. “In our case, this would be actual patient data that is run on the individual to know whether or not they have the disease.”

Though Gehrke and his partners have already created a prototype for the app, they are still trying to create a culturally appropriate interface for the countries where people would be using it.

“Being able to quickly isolate someone and know they have Ebola within 10 to 15 minutes is extremely beneficial,” said Nicole Carloni, a graduate student in Boston University’s School of Public Health who has been working with Ebola patients in Sierra Leone for the past three weeks.

However, she said one of the main problems in Sierra Leone is that potentially sick people are not coming forward for treatment. Carloni said she has been working on a social mobilization campaign to educate locals.

The epidemic in Sierra Leone has plateaued, Carloni said. While the number of cases per week has gone down from 3,000 at its peak to around 70, it has stayed at that rate for the past few weeks. While that sounds like good news, it also poses its own problems.

“Now that the number of cases is going down, it’s almost harder to find the areas that are affected because there’s fewer cases to track,” she said.

William Yen, a sophomore in the College of Engineering, said while this new technology could become the standard for diagnostic testing, educating the public about Ebola is a more efficient way to prevent the spread.

“I do not believe that this test will be able to prevent the spread of Ebola as efficiently as properly educating the public about Ebola, its symptoms and how it is spread. Contrary to popular belief, Ebola isn’t actually that transmissible. The measles outbreak in California is actually more transmissible than Ebola,” he said. “The only difference is that we have a vaccine for measles. Now, that being said, this test will still be very helpful in the treatment of Ebola, which can be better treated if discovered in its early stages.”

With the Ebola epidemic waning, Gehrke said one of the challenges he and his collaborators are facing is predicting what the next epidemic will be.

“In other parts of the world, there are other serious hemorrhagic diseases like Argentine hemorrhagic virus,” he said. “The challenge is to try to be ready so we have a device that can detect these emerging pathogens to help the treatment of the patients.”