Wealthier students in the United States have higher rates of success in earning bachelor’s degrees, according to a report released Wednesday by The Pell Institute for the Study of Opportunity in Higher Education.

The report is a partnership project between the Pell Institute and the University of Pennsylvania Alliance for Higher Education and Democracy, said Pell Institute director Margaret Cahalan.

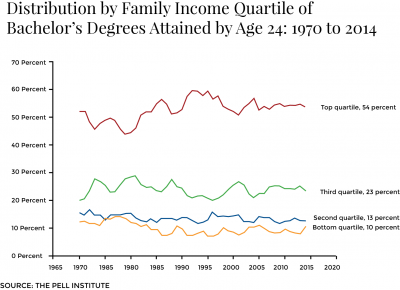

Of the bachelor’s degrees earned in 2014, 77 percent were accounted for by the top two quartiles, the report stated. In 2015, 54 percent of dependent top-quartile family members aged 18 to 24 attained a bachelor’s degree by the age of 24.

The report was constructed with data from the U.S Census Bureau and the National Center for Education Statistics to examine issues of equity in higher education, Cahalan explained.

“This report reviews the statistics, tracks what we’re doing and also tries to address, based on the information in the statistics, what information … we need to make things more equal in terms of higher education,” Cahalan said. “This data has revealed that we do need better data to understand what’s happening and that it’s happening.”

A large disparity among students from families with different levels of income and students with different levels of income themselves have widely varying experiences in higher education, Cahalan said.

“The data clearly are showing we have a very stratified system, and this is growing,” Cahalan said. “We have more or less one system for students who don’t have a lot of family resources, another system for middle-income students and we have another system for the richer students.

The “three-tiered system” previously mentioned would have implications on the country’s “intergenerational mobility,” Cahalan said.

Ann Cudd, dean of Boston University’s College of Arts and Sciences, said inequality in higher education is improving slightly in favor of low-income students.

“There has been high inequality for a long time between different income levels in terms of higher education,” Cudd said. “But, in fact, it looks like the gap is narrowing slightly, which is good news … because the bottom is going up.”

Despite this statement, Cudd said the gap still poses an issue for low-income students seeking a degree.

“Education is the road to social mobility, and if it’s unequal in the way it’s distributed, it won’t change mobility of the least advantaged members of society,” Cudd said.

Several BU students said low-income students face greater obstacles that limit their potential to achieve certain higher education degrees.

James Butkevicius, a junior in the College of Communication, said insufficient financial aid systems do not helping students in need achieve degrees to improve their lives.

“[Current] financial aid as a system … is creating a situation where people are either getting turned away or falling into more debt,” he said. “A college education is basically required for jobs within a certain income range. It’s a debate that has gone on for a long time — the rich getting richer and poor getting poorer.”

Colin Stuart, a sophomore in CAS, said social factors such as a student’s family dynamics could impact their academic success.

“Family stress can affect academic success,” he said. “If your family is financially stable and you don’t have to worry about putting food on the table, you can focus on academics. Also, someone who is working a job or two in high school won’t have time to study for classes or SATs or anything.”

Zein Eltigani, a junior in the Sargent College of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences, said a student’s socioeconomic situation has a complicated effect on their performance in school long before college.

“Depending on your family’s income, where you live, a lot of socioeconomic factors affect the kind of school you go to and, from there, what you do for college,” she said. “There should be a push for making colleges more accessible for low-income students. College is so expensive, so it makes it difficult.”