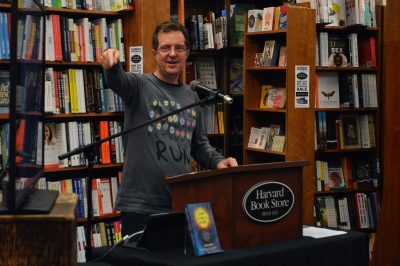

Author George Musser arrived at the Harvard Book Store on Monday evening wearing a “Stranger Things” T-shirt and managed to work references to the TV show into two of the slides of his book presentation.

Musser’s 2015 book “Spooky Action at a Distance: The Phenomenon That Reimagines Space and Time — and What It Means for Black Holes, the Big Bang, and Theories of Everything,” about nonlocality and quantum entanglement, will be released in paperback on Nov. 15 through Amazon.

“I consider the paperback really the definitive edition of my book,” Musser said, before noting that he only made a few changes from the original hardcover copy. “One thing I did add was a very short, three-page appendix.” In the appendix, he covered “the imperfect crystal” idea that is used in the book, which he said many readers wanted to explore after reading the hardcover edition.

Greg Kestin, a Harvard University Ph.D. student studying physics who recently worked with the PBS program NOVA on a video about cosmic inflation, recently met Musser at a conference and attended Monday evening’s event. He said Musser did a good job explaining the random odds coin metaphor, which says the odds of getting heads and tails is not actually equal, in his book, and applying it to the real world.

“Even if you think about quantum mechanics frequently, you might not have an immediate answer… but George does a really good job of fielding those questions,” Kestin said. “Sometimes a metaphor will add, sometimes a metaphor will do injustice to what’s actually going on, but [Musser] did a really good job of using the coin metaphor, which … I feel like that does a good job of explaining what’s going on under the surface.”

Amanda Gefter, a fellow science writer and author of “Trespassing on Einstein’s Lawn,” a memoir about her journey to becoming a science journalist. Gefter first met Musser when she pitched a story to Scientific American magazine.

“He’s such a beautiful writer,” Gefter said. “We write on a lot of similar topics.”

Gefter also wrote a review of Musser’s first book, “The Complete Idiot’s Guide to String Theory,” for New Scientist magazine, which he was happy about. “I’ll always be grateful to you,” Musser told Gefter after the event.

“The Complete Idiot’s Guide to String Theory,” the 2008 predecessor of “Spooky Action at a Distance,” is Musser’s first long-form exploration into science writing. In the past, he had mostly worked on shorter articles and his graduate thesis.

Musser said his editor wanted to branch out a little bit and do more highbrow topics than some of the other subjects in the “Complete Idiot’s Guide” series, so he asked Musser if he knew of any writers who might be interested in working on that. Musser did know such a writer: himself. He liked how it was a more defined project than anything he’d done before. He needed to define string theory and explain his own take on it.

In the meantime, Musser works as a project-based contributing editor for Scientific American, where he has worked for over a decade. He said he found a science editor job listing online based in California for the Astronomical Society of the Pacific’s Mercury Magazine, where he worked before becoming a senior editor at Scientific American.

Musser also has a little lab in his basement, where he did one of his entanglement experiments, as he’s still interested in the participatory side of the sciences. In fact, he said he originally wanted to do cryptography, so he studied math before eventually majoring in electrical engineering at Brown University. After Brown, he took some time off to explore the world before returning to the United States and attending Cornell University as a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellow studying planetary science.

“Part of me never wants to write another book again,” he said, laughing. “On the other hand, you never really have that opportunity to drill into something so intensively. If I did another book, it would probably be on consciousness.”

Tom Ryder • Nov 16, 2016 at 7:08 pm

I look forward to reading the published works.