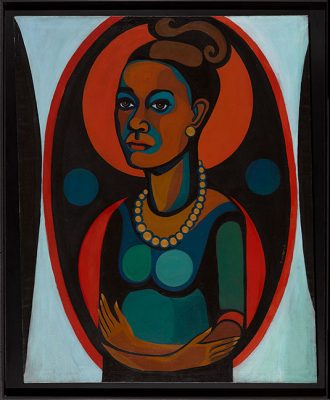

Small dots appear in painted canvases hanging on walls in a new exhibit at the Institute of Contemporary Art. Though inconspicuous at first glance, the little circles shine light into painful times in the artist’s past.

Howardena Pindell grew up in the midst of segregation in the 1950s and ‘60s. As a child, she was given a root beer at a stand with a circular, red sticker on the bottom to signify the cup was meant for a person of color. The dots in her art symbolize those stickers that labeled her “other.”

Pindell, who graduated from Boston University’s School of Fine and Applied Arts in 1965, created the paintings for the exhibition “We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965-85,” currently at the ICA.

The showcase was organized by the Brooklyn Museum and contains paintings, print, videos, sculptures and photography by over a dozen black female artists. The work mainly focuses on the lives of women of color during the second wave of feminism in the United States in the 1960s.

Logan Roche, an employee of the ICA, said the exhibition aimed to show the work of a population of artists who were underrepresented in the movement dominated by the white middle class.

“Whose voice is heard in different groups, who is included in that conversation and who is overlooked?” Roche asked.

Among the work of many other black female artists featured in the exhibition, Pindell’s sizeable canvases are easily recognized by her signature dots that are cut from paper and layered with other materials.

“We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965-85” also includes a film produced by Pindell, “Free, White and 21.” The 1980 film shows Pindell recounting her experiences encountering racism. She spoke of her teacher not allowing her to go to the bathroom during a time reserved for the young students to sleep and the teacher tying Pindell down to the bed in anger for a couple of hours.

Caroline Losneck, a journalist from Maine, walked away from the exhibit thinking about problems within the feminist movement.

“[The exhibition] shows how feminism is led by white women and excludes women of color,” Losneck said. “That really resonates with what’s going on right now. It raises questions with how racism is entrenched even within the progressive and art worlds … We have a lot of work to go.”

Roche observed African influence in many of the pieces and attributed this to popular artistic collectives that many of the painters belonged to. The collectives created manifestos and agreed upon techniques and style guidelines for artists that belonged to them.

Several of the women whose work appears in the exhibit belonged to a collective called AFRICOBRA. Artists such as Elizabeth Catlett, whose sculpture, “Target,” is on display at this showcase, and Jae Jarrell participated in the collective that honed in on African heritage.

“A lot of people and artists find identity through discovering their heritage and practicing engaging with it,” Roche said.

Losneck said that she enjoyed reading the prints in the gallery. She said she felt the other types of artwork originated from a distinctly different time period while the prints made the exhibit relate to current times.

“The photograph seems old,” she said. “Then you read it, and it seems as though it could be going on today.”

“We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965-85” will be shown in the Karen and Brian Conway Galleries of the ICA Boston until Sept. 30.

Very nice piece, Samantha. Keep up the excellent work. This takes me back to my days a l-o-o-ng time ago as arts editor at The Daily Orange, the independent daily at Syracuse U. Of course, then, it was strictly print, no web.