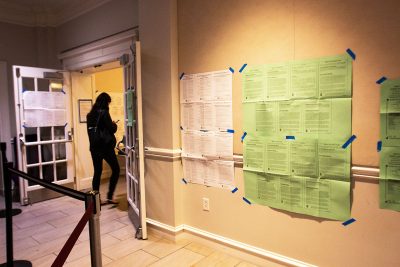

In Tuesday’s municipal election, 17 percent of all registered voters — as of September — cast their ballots for Boston’s at-large City Council members, a dip of more than 10 percent compared to the last election in 2017.

Every two years, Bostonians head to the polls to pick their representatives for all 13 city council seats, which include four city councilor at-large positions and nine district councilor seats. The 2019 ballot also polled voters on whether they were in favor of renaming Dudley Square to Nubian Square (they were not).

Voter turnout for Boston’s city council elections have historically lagged behind federal and Massachusetts state elections, according to voting records released by the Boston Department of Elections. Over the past two decades, an average of 25 percent of registered voters cast their ballots each election for the City’s at-large council members.

The number of ballots cast during the past 20 years of City Council elections have not exceeded 40 percent, with the highest being 38 percent in 2013 and the lowest being 13 percent in 2007 and 2015, according to the records. From 1999 to 2019, total turnout percentage has fluctuated up or down by more than 10 percent for every at-large election.

Low turnout is not a trend unique to Boston, especially as municipal elections typically occur off-cycle from presidential and congressional years. Compared to the federal and state levels, they tend to draw minimal voter attention.

MassVOTE Deputy Director Tegan George said presidential elections incentivize more individuals to vote because these campaigns inundate communities with advertisements and events, and people generally get more excited over such a large-scale event every four years.

“It’s harder to harness that energy around local races, even though local races are often the ones that impact us as individuals and as residents of our towns and cities the most,” George said.

College students prove a challenging demographic to mobilize, George said, because many no longer live in their home state. They may be unsure where they are registered, or are registered at home but have not updated to their new location.

“And it’s harder to mobilize [Get Out The Vote] around college students because they have nontraditional schedules compared to someone who works a nine-to-five,” George said. “In the past it was hard to get folks registered if they live in dorms. That has progressed really nicely.”

Students today can change their residency to their dorm address when updating voter registration information. Meanwhile, those who prefer to remain registered in their home state can vote absentee.

Caroline Mak, research and field coordinator at Nonprofit VOTE, said she believes the low turnout rates for municipal elections correlate to lack of knowledge.

“I think that goes hand in hand with not knowing what’s on the ballot,” Mak said. “You don’t know the candidates, therefore you’re not really excited about them, therefore you don’t really know what’s going on or even when the elections are.”

Primary responsibilities of the City Council include reviewing and approving Boston’s annual budget, voting on policies to send to the mayor for final approval and appropriating the money to fund city projects.

Mak said that when she was in her second year at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, she didn’t perceive local politics to be of importance to her.

“I remember being a sophomore and seeing a poster for [a] forum being like, ‘There is a Cambridge City Council panel,’ and it’s like, what does that have to do with me?” Mak said. “I have homework to do, I’m not really interested.”

However, Mak said many community issues can directly impact students. Sometimes policies specifically affect them, such as the Boston Licensing Board’s indefinite ban on MIT fraternity parties in 2013, but more often the reverberations are low-key.

“If you want to live on campus or in summer housing — especially in the Boston, Cambridge, Somerville area, where housing prices are really expensive — you have a very direct stake in having affordable housing,” Mak said.

Municipal race results can be “razor-thin,” according to George. Every vote counts more when so few participate.

“Voting is your most sacred civic duty as an American citizen,” George said. “It’s really the only way to have your voice heard and part of the best way to have your voice heard. And it’s fun to get your ‘Voted’ sticker; I still get so excited about stuff like that.”

Dorchester resident Reginald Busby, 52, said he does not vote in federal elections because he doesn’t believe they make a difference. But local elections are a different story, he said.

“Because you live there, it’s just more direct. I guess you’re closer to the government,” Busby said. “Washington’s like an abstract thought, so far away. And those people don’t interact with us.”

Brandon Thomas, 25, of the North End, said he thinks municipal elections are “absolutely more important” than federal or state.

“We can impact our environment, keep things from impacting our environment,” Thomas said. “And it’s just a better, more tangible way of seeing how you function in the civil process.”

Ansley Moore, 19, of Downtown Boston, said she likes to vote in any election available to her.

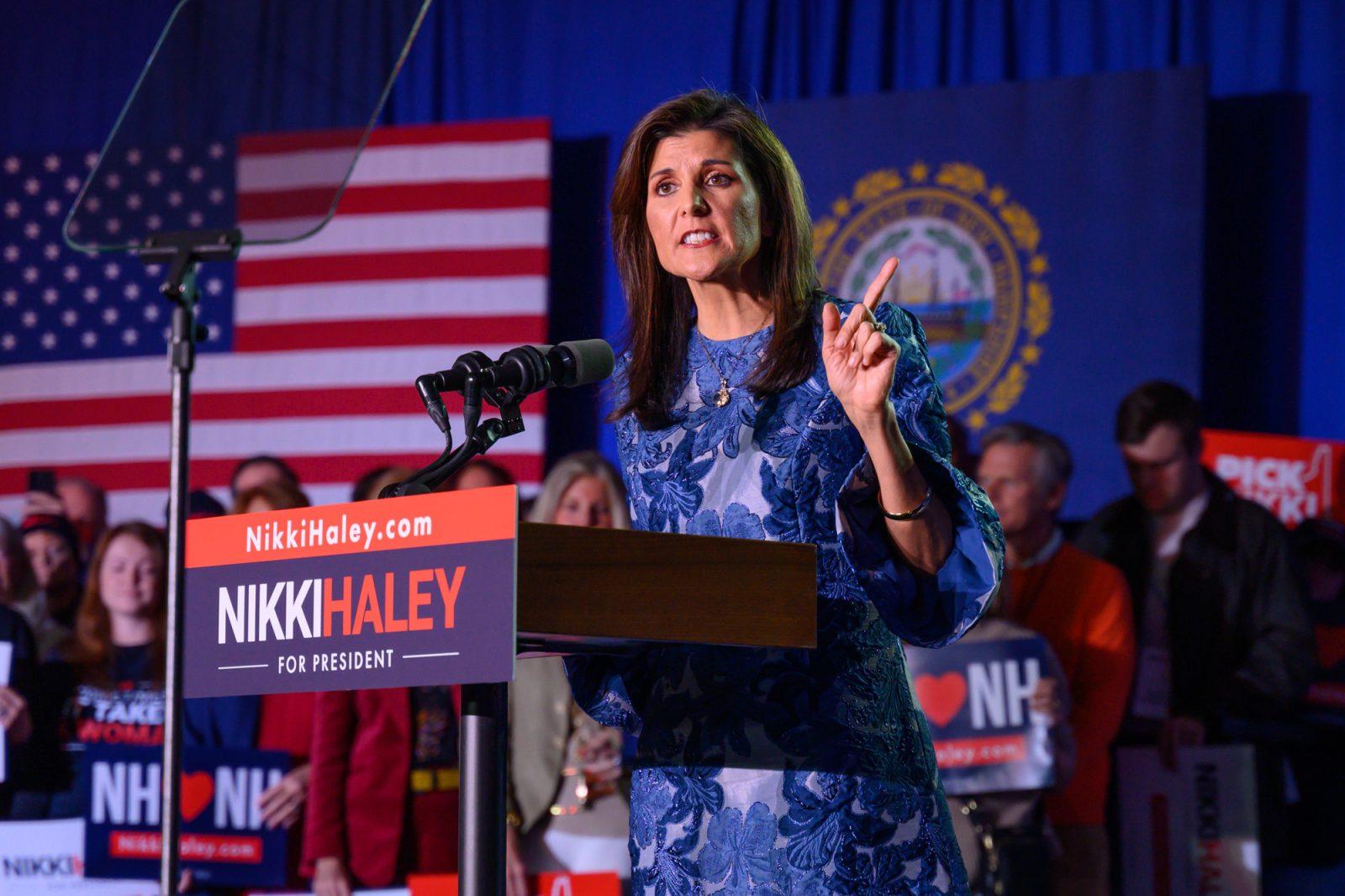

“Smaller elections often get overlooked, even though they impact your life more directly, but also the people that win those offices are the people that have the power to run for presidential elections in the future,” Moore said. “And so by taking those elections for granted, you’re jeopardizing your future.”