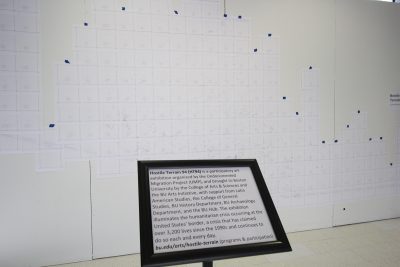

For now, “Hostile Terrain 94” is as barren as the Sonoran Desert it depicts. Soon, it will be lush with more than 3,200 toe tags representing the remains of those who died trying to cross the U.S.-Mexico border.

HT94 is a participatory art exhibition that relies on members of the Boston University community to add these tags to its map, marking where the tag owner’s remains were uncovered in Arizona. Brought to BU Sept. 3 by the College of Arts and Sciences and the BU Arts Initiative, the project will be on display on the second-floor landing of the George Sherman Union until December.

Ty Furman, managing director of the BU Arts Initiative, said he hopes that introducing artistic explorations such as HT94 can engage students and make curated art more accessible to the BU community.

“As a person, I’m really drawn to arts around social justice issues,” Furman said. “I’m drawn to projects and exploration that challenges you to think about who you are, your place in the world and other people’s place in the world.”

Furman said he thinks HT94 will work to humanize the border crisis, showing audiences that immigrants are simply people striving to enter better circumstances for themselves or their families.

“I think we’re in a particular political climate with leadership that is demonizing migration in a way that it has not been for a long time or exponentially more than it has been in the past,” Furman said. “I think that it’s important that we humanize this, the idea that people seek to make their lives better for their families.”

The Undocumented Migration Project brought the idea to life, and the exhibit will simultaneously be staged in 150 places across the world this fall. UMP focuses on U.S. immigration and its specific minority populations, and uses methods ranging from archaeology to anthropology to better understand human rights violations at the border, as well as their larger political repercussions.

The name “HT94” is a reference to a border policy created by former President Bill Clinton’s administration in 1994 dubbed “Prevention Through Deterrence,” which attempted to discourage migration by heightening security at major entry points and instead funneling migrants through the Arizona desert, deemed by the U.S. Border Patrol as “hostile terrain.”

However, more than 6 million people have attempted the crossing since the 1990s, according to the BU Arts Initiative, and more than 3,200 of them are confirmed to have died due to the desert’s conditions. PTD remains the primary method of border control today.

One goal of HT94 is to allow the public to actively add to the piece. Volunteers can fill out the toe tags themselves, each of which lists information — such as cause of death and geographic location — on one of 3,200 deceased migrants. These toe tags will be placed accurately on the map to show where each life was lost.

Students, faculty and other BU community members can sign up for a time slot to fill out tags online. Students can also participate in the “Hostile Terrain 94: Immigration, Politics, and Activism Through the Arts” cocurricular this semester, available on the Student Link.

Archaeology professor David Carballo said students enrolled in the cocurricular will earn a BU Hub credit for “The Individual in Community” because HT94 allows students to think critically about what constitutes a society.

“The borders define communities. They are part of the way that we have debates about community, what is national community,” Carballo said. “Through [the cocurricular], we really want students to take ownership of the exhibit, that students are helping not just to assemble it, but then also to present it to the BU community.”

BU students will also have access to a showing of the 2019 documentary “Border South” on Sept. 24, as well as a panel discussion in October to reflect on the exhibit.

Maria Shevchuk, a sophomore in the College of Engineering, said that as a Russian immigrant, she is glad HT94 brings attention to migration issues.

“I think it’s really cool that more attention is being brought to things like immigration because I’m personally foreign to here,” Shevchuk said. “I can totally relate to this, and I think it’s awesome.”

Carballo said that above all, he hopes participants and viewers realize the extent that PTD policies have affected and continue to affect immigrant and American lives.

“I hope that there’s an awareness that this policy is just another example of something that creates first- and second-class people, instead of citizens or just humans. It is contributing to inequality in different ways,” Carballo said. “We’re not treating humans with dignity. This policy is part of that.”