A tribute to David Graeber (1961–2020) and an exploration of his theory of “Bulls— Jobs.”

In 1930, Economist John Maynard Keynes predicted that by the end of the century, developed countries such as the United States and United Kingdom would have a 15-hour work week as a result of advanced technology. Keynes was right about the technology, but 15-hour work weeks are nowhere to be found.

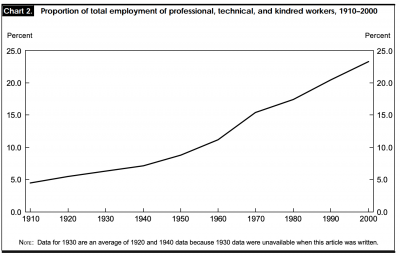

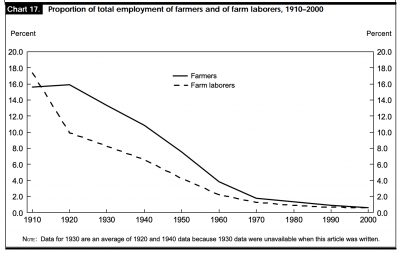

Over the last century, the number of jobs in manufacturing and agriculture have fallen dramatically while managerial, clerical, sales and service jobs soared.

As predicted by Keynes, productive jobs — those that actually produce wealth — have been significantly overtaken by automatic beings.

Keynes’s world never materialized despite clear technological advances suggesting that it could have — why didn’t it?

Some argue such a world didn’t arise because Keynes didn’t factor in all the shiny things such as smart devices, designer jeans and all things battery-operated.

It’s a compelling point at first glance. Consider the average man of Keynes’s day — absolutely no drip. Furthermore, many of us attribute a great deal of our current standard of living to relatively recent technological advancements.

However, here’s the issue: the number of jobs that actually have anything to do with producing commodities — shiny, cool things — in developed modern day society are few and far between. That is not to say we simply offshored our production jobs, but that technology has made the overall share of manufacturing jobs fall dramatically.

Since technology has lessened the labor needed to sustain our standard of living, we have had to collectively make a choice — give people more free time to pursue their passions outside of work or make more jobs.

Our society, influenced by capital, has chosen the latter. This “give them work” attitude was the catalyst for the administrative sector of the economy — unprecedented expansion of sectors such as corporate law, academic and health administration, human resources and public relations. The alternative would be mass unemployment.

Although a truly objective measure of social value is impossible, the coronavirus has taught us a great deal about the role of our society’s jobs. A world without the service sector — sustained by those who stock the grocery stores, tend to the sick and take away our garbage — will immediately and catastrophically grind to a halt.

By contrast, a society without the newly expanded administration sector featuring public relations firms, education and health services could actually be something of an improvement.

A 2013 Gallup study found that about 70 percent of Americans are disengaged with their job. Why is it so hard for people to find meaningful work? That’s a complex question, but one way to search for an answer is by learning about Karl Marx’s Theory of Alienation.

Marx defined alienation as “the process whereby the worker is made to feel foreign to the products of his/her own labor.” Marx’s issue with alienation in capitalism was that the worker does not own the products of their labor — so where does that leave us?

Well, most jobs today don’t produce commodities. In fact, an astoundingly small number of our jobs produce anything at all, with 84 percent of our economy being characterized as service-providing as opposed to goods-producing jobs.

It is true, however, that in today’s service economy, the service itself can be considered a commodity. Consider the job of the grocery worker. Their role is not to produce the groceries themselves, but rather to provide the service and labor to distribute the groceries to the community in exchange for money.

These are not the jobs Graeber is referring to in “Bulls— Jobs.” Instead, he is challenging the expansion of the administrative sector.

If 1 percent of the population controls most of the country’s disposable wealth and owns 50 percent of its stocks, then what we call “the market” will reflect what they think is useful or important. The explosion of jobs within corporate law and PR firms, administration in education and health care, and beyond, reflects the ability of the ruling class to shape society.

Think about who is legitimately served by any of the jobs listed. It’s not you or me. The majority of jobs emerging in administration exist to uphold capitalism and guard corporate power.

Administrative jobs stray even further from Marx’s model of “fulfilling work” than the standard service job does. Unlike some service work, administrative jobs do not provide a service for others so much as they provide a service to a business. Corporate lawyers serve to legally protect the earnings of corporations. PR and telemarketing firms serve to maximize a corporation’s profit through targeted advertisement.

Despite these jobs being high in demand and — usually — wage, they see the highest levels of alienation and unhappiness. More than half of the 20 unhappiest jobs in the country are principally administrative in nature, according to a Business Insider and CareerBliss study.

Since the work displayed in these jobs results in such detachment between a worker and any product of their labor, bulls— jobs yield some of the greatest unhappiness of any occupation, and thus alienation.

Whole industries and job markets have been created with the intention of keeping people busy rather than serving any real economic role — it’s no wonder they find little purpose in their jobs.