In the midst of a widespread social movement for racial justice, some activists have begun to wonder whether raising awareness is equivalent to action.

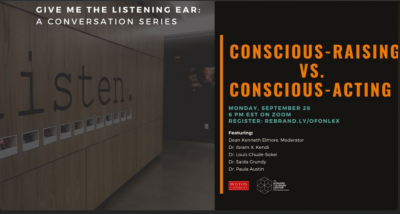

On Monday, the Howard Thurman Center for Common Ground hosted a panel entitled “Conscious Raising vs. Conscious Acting,” moderated by Boston University Dean of Students Kenneth Elmore.

Panelists included Ibram X. Kendi, director of BU’s new Center for Antiracism Research, and other BU professors. The event is the first in a series of panels that will address questions of justice, community and racial reconciliation.

Elmore introduced the event by asking panelists about their outlook on the current state of equity and equality in the United States.

Saida Grundy, assistant professor of sociology and African American studies, said the current circumstances make right now an ideal moment to be analyzing these issues.

“I think it’s a very opportune time,” Grunday said, “because you not only get to autopsy social problems as they are happening, you sometimes have a play in where things are going because you connect to those pieces.”

Louis Chude-Sokei, director of BU’s African American Studies program, agreed with Grundy, adding that this is an important time for students to take action and hold systems accountable.

“Much of what we’re seeing, I believe, is the toss-up and chaos of old orders that are crumbling and are struggling to establish themselves and draw lines around themselves and retrench,” Chude-Sokei said during the talk. “As dark as things seem, I envy the really young right now, because you’re more than likely going to be the ones on the other side of it.”

Grundy said the American voting system is far less oppressive than it has been in past generations, which is why he said young people and people of color should take advantage of their ability to vote.

“The Republican Party spent $40 million during 2010 to gerrymander these districts so that young people and people of color could not vote,” Grundy said in the panel. “If your vote didn’t matter, there seems to be a whole lot of effort to keep you from doing it. That’s exactly how much it matters.”

Grundy said voter suppression was designed to keep Black people away from polls, and that while the voting system has its faults, it has progressed over the years and is a form of activism that students should participate in.

In an interview after the event, Grundy said a strategy in voter suppression involved the spread of misinformation, which leads to the kind of confusion that keeps people from going to the polls.

She said these campaigns are successful because they target young people who tend to be transient residents in their surrounding communities. These voters can at times be “a little bit off the grid,” Grundy said, as they often are not homeowners or do not hold a job in that area.

“Young people tend to vote progressively,” Grundy said. “They tend to vote in ways that really hold politicians accountable.”

Comparing activism to a battlefield, Grundy said that as an educator, her role is to prepare students for battle. She does so by helping students understand the history of suppressing the vote of people of color.

Paula Austin, an assistant professor of history and African American studies, said teaching with an antiracist approach shouldn’t be linked to specific areas of study. An instructor can teach a subject not related to race, she said, and still maintain an antiracist curriculum.

“You don’t have to be teaching about a minoritized or marginalized community in order to be teaching about antiracism,” Austin said after the event.

As a historian and researcher, Austin also drew comparisons between movements of the past and the modern-day effort for education and restorative justice that has transpired in the past few years.

“The linkages between the history that I teach and know about and our contemporary political, social, cultural moment,” Austin said, “those relationships feel very strong and visible right now, palpable.”

While panelists did not have time to compare raising awareness and taking action as forms of activism, Austin said both strategies should be seen as stages of activism as opposed to differing ideas to combat racial injustice.

“I do think politicization, which comes through consciousness-raising, is an incredibly important step,” Austin said. “You don’t just wake up and, through your identity, say, ‘Oh, I’m like these people, and these people are organizing about this issue.’”

Raising social awareness by making issues political, Austin said, can hold authorities accountable. For those in power to take action, the public must be vocal and focused in their demands for racial justice.

Austin also said that while some may consider studying political education as a form of consciousness-raising, she considered it a form of action. She said consciousness-raising need not be separated from consciousness-action, but rather expanded.

“The ‘versus’ only helps to reinforce this idea that political action looks a certain way, and that’s a false idea. It’s a false idea that’s born out in history,” Austin said. “People are engaged politically at all different levels, at all different ages and all different registers, and we need all of those things to make movements successful.”