For every viral image of a dinghy overflowing with passengers crossing an ocean or families packed into tents in a refugee camp, there are millions more people, unphotographed, experiencing the same suffering. They have been displaced in the Middle East and beyond by wars stemming from the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001.

David Vine, a professor of anthropology at American University, discussed Wednesday the past 20 years of conflict and its repercussions for the refugee crisis through the Frederick S. Pardee Center for the Study of the Longer-Range Future and Brown University’s Costs of War Project.

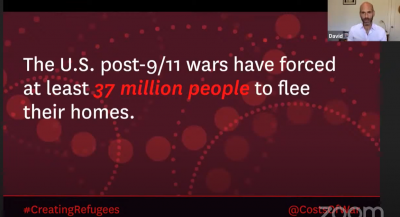

In the presentation, entitled “Creating Refugees: Displacement Caused by the Post-9/11 Wars,” Vine examined the wide-reaching impact of this violence on migration since 2001.

“It’s difficult to conceive of what 37 million people displaced actually means,” Vine said during the presentation. “Our report encourages people to try to wrap their minds around what that means, what it means to be displaced for a single individual, for a single family, for a single community.”

Vine’s research team focused on violence and displacement stemming from wars in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Yemen, Somalia, the Philippines, Iraq, Libya and Syria, all of which the United States either launched, escalated or engaged in as a major combatant after 9/11.

The team found 8 million people were displaced from these countries internationally, while 29 million were displaced internally, as a result of these eight wars.

“The total damage inflicted on the Middle East as a region, the Middle East as a whole, is very difficult to comprehend. It’s so profound,” Vine said in an interview. “That sort of damage alone needs repair, and I think the U.S. has a responsibility to help in that repair.”

People who have to flee their homes due to forced displacement suffer trauma that spans years beyond their initial movement, Vine said, and endures even after they may have found safe haven.

“There is no way that you can ever return someone to where they were before these wars,” he added. “There’s no way to fix the damage completely, but that doesn’t mean we can’t try and doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try.”

While sole responsibility for the displacement in the Middle East does not rest with the United States, Vine said, the country is one of several actors involved in the post-9/11 wars including the Islamic State, the Taliban and U.S. allies in NATO countries.

“Displacement, like pretty much every phenomenon in the world, is a hugely complicated one,” he said during the talk. “One can never identify a single cause behind the displacement of a single individual, or a single family, or a community.”

Vine identified several policy proposals for the U.S. to begin repairing its post-9/11 damage to displaced people. These include admitting more refugees, increasing global and domestic refugee funding and thinking about whether war is a legitimate policy option.

Refugee admissions to the U.S. have dropped to record-low numbers, the most recent being 15,000 for the 2021 fiscal year, according to a statement released last week by the U.S. Department of State.

The fate of refugees seeking to enter the country, Vine said, largely depends on the outcome of the upcoming presidential election.

“If Trump were to win, I expect no change or only a further downward movement in the numbers accepted,” Vine said in an interview. “And if Biden wins, I think there’s a real chance to not just bring the acceptance numbers back to where the Obama-Biden administration had it but to, in my mind, as I said in the talk, expand the numbers of refugees accepted significantly.”

Financially, the post-9/11 wars have created a debt problem in the United States. Unlike previous wars, which were largely paid for by increasing taxes and integrating the war budget into the regular defense budget, these conflicts are economically adding up, according to a 2017 report by Linda J. Bilmes of Harvard University.

The issue with turning to debt and keeping taxes low, Vine said, is that many Americans have yet to contend with the wars’ financial impacts.

“This is another way in which U.S. citizens haven’t felt the wars: they haven’t had to pay for them directly, they haven’t felt it in their pocketbook,” Vine said in an interview. “But by doing this, you’re just pushing off the financial pain to future generations that will have to pay off the mounting government debt.”

During the presentation, Vine called the impact of the post-9/11 wars “incalculable.”

“We don’t want to just leave it at 37 million, because of course, the damage of displacement is ultimately incalculable,” Vine said. “Incalculable for any one individual, incalculable for a family, for a community, and that’s where we would like to place the emphasis: on the people displaced and what they have experienced, what they have suffered.”