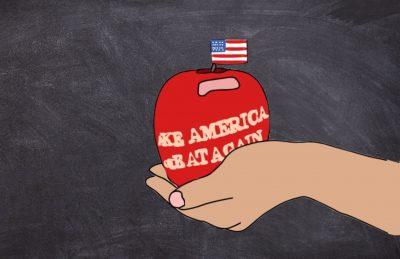

An O’Maley Innovation Middle School teacher in Gloucester asked her students who they were supporting in the Nov. 3 presidential election. 12-year-old student Jackson Cody answered with President Donald Trump, and the teacher’s response was nothing less than ostracizing.

“Really, Mr. Jackson, I thought I liked you,” the teacher said.

Cody hired an attorney, but is not pursuing action beyond asking that the school hold immediate training on the importance of respecting differing beliefs, an apology from her and a promise that such behavior will not happen again.

While the teacher might have been joking, it is not her or any educator’s role to interject such belittlement onto a child. Children must feel respected and validated so that they will not only trust their instructor, but also feel confident enough to start developing their political identity.

The teacher put herself in the position to alienate this student by prompting the conversation. She asked her students who they were supporting, and they answered accordingly. We may live in a blue state in Massachusetts, but she should not assume that everyone’s political views would align with hers — Cody’s response was not unwarranted.

The teacher’s remark was too emotional. If you are to teach politics to young children, it must be done in a thoughtful way and without such a strict binary. There is more to politics than simply voting for a candidate.

This teacher was not wrong for bringing politics into the classroom — it belongs there to some extent. But if her motivation was to sway the opinions of her students and team up with those who are opposed to Trump, then her focus was inapt.

Students were forced to blindly declare candidate loyalty without any form of guidance. There needs to be more context and substance to the lesson rather than dividing the class along partisan lines.

Teachers should be transparent about their own biases and beliefs so that students can have an appropriate view of their instructor. Then, to the best of their ability, they should teach the material objectively — present the facts in a digestible way that will allow young minds the opportunity to begin forming their own opinions.

It’s more valuable for children to understand how the government works than be forced to align with a political party. We must give kids the benefit of the doubt that they do not understand politics, and instead of asking them to claim a particular identity, we should help them begin forming their political ideologies.

When elementary and middle school teachers run mock presidential elections, they are more a comparison of what the students’ families believe rather than of these kids’ actual party loyalties.

For kids, it’s about donkeys versus elephants — not access to abortions and tax brackets.

How can we hold children to such a high standard and expect them to have a thorough understanding of politics when so much of it is not yet even in their realm of comprehension?

Most parents probably won’t introduce politics to them until facets of it start affecting their life or they start asking questions. Political awakening is a personal journey — not one that can be forced by the education system.

In the case of the middle school teacher-turned-bully, her antagonistic views most likely strengthened the child’s loyalty to Trump as a reactionary effect of wanting to defy the institution.

The conflict between personal conviction and institutional belief only worsens as you get older.

College greatly differs from lower levels of education because students are no longer faced simply with teachers trying to mold their minds. Congregating in a new environment encourages a newfound social understanding between peers with shared backgrounds and beliefs.

Upon coming to college, you realize how much of the world is beyond your hometown. Your views are suddenly validated by others, oftentimes at higher rates than they were before, and your opinions become more solidified.

That same idea of commonality and open spaces for all views should be applied at all levels of education.

While discussing politics isn’t meant for elementary children, we can start instilling from a young age the idea that everyone’s opinion is valid. You don’t need a political affiliation to understand that.